As the population heads toward 9 billion, pressure rises for more housing. Meeting the global demand, however, is more complex than simply building more homes and shelters. Why? Current housing design is highly resource intensive, which makes sustainable building challenging. While forms of housing and shelter vary across regions, they share two common functions: providing protection and reflecting the local context. The current housing design favors low-cost, easily assembled, and highly replicable construction materials. Oftentimes, this leads to housing that is not suitable for certain local challenges. Those can include houses that are not stabilized in flood-prone regions or windowless structures in hot climates. To live comfortably and sustainably, we must take historical, cultural, and environmental context into consideration.

Sustainable construction with unconventional materials

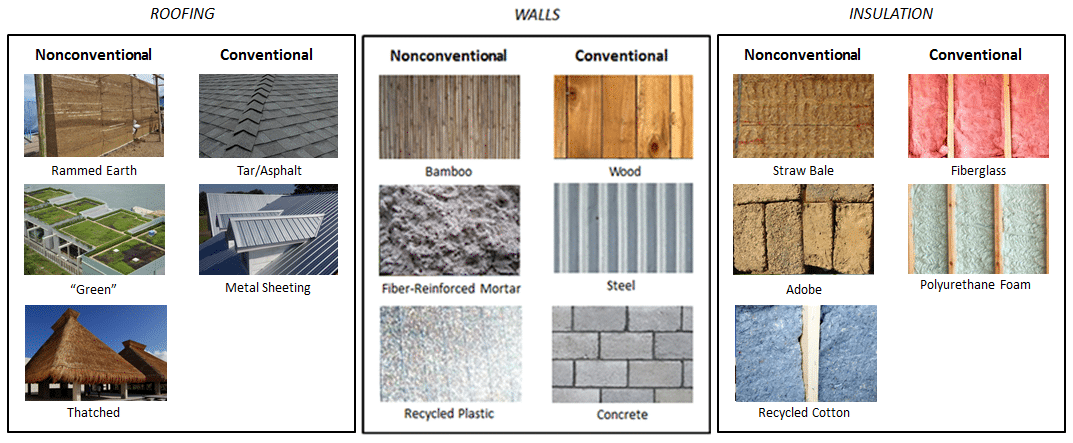

Sustainable building solutions call for environmentally friendly materials, waste reduction, and a commitment to meet the long-term demands of a growing population. A good way to meet those conditions is to build with non-traditional materials. These are materials that can be used lieu of the wood, tin, and concrete that is common in construction now. Unconventional materials like the ones pictured below have evolved through adaptation of local resources, longstanding cultural practices, and indigenous knowledge. They typically have the advantages of being environmentally friendly and locally abundant.

As a byproduct of widespread use, conventional materials have the benefits of established global supply chains and low production costs made possible by mass manufacturing. Nonetheless, these materials are not sustainable building solutions because they can drain natural resources, require significant processing, and generate waste. As a result, we need to select housing materials that are sustainable and functional with respect to a given context.

How to assess the sustainability of materials

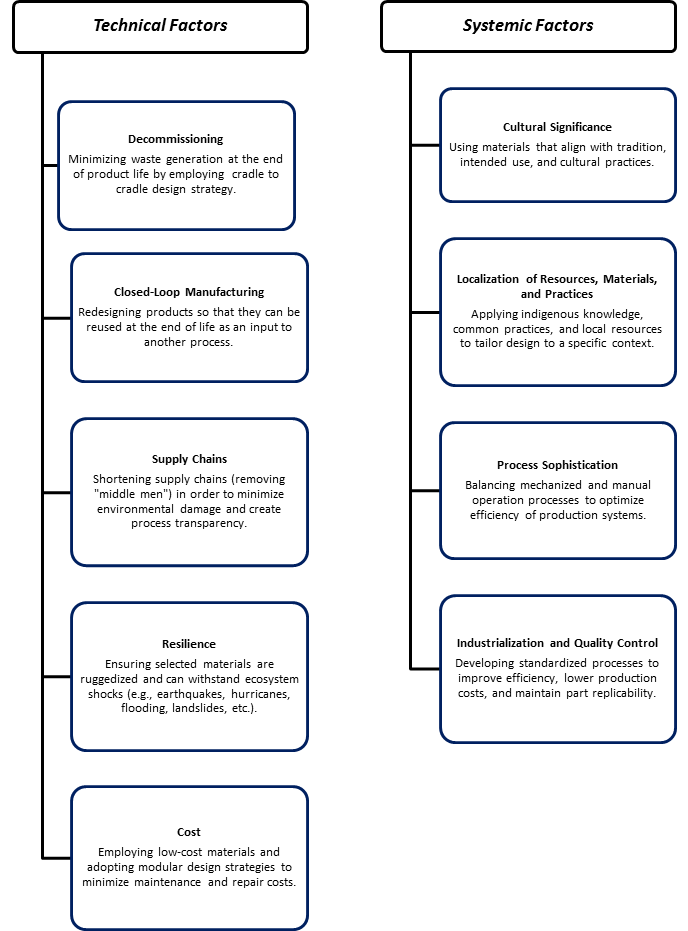

To do this, we have identified a set of criteria that can be used to assess the sustainability and scalability of both conventional and unconventional construction materials. “Sustainable-scale” design incorporates both technical and systemic factors in the material decision-making process and guides designers to consider the environmental, social, and economic implications of material choices.

Deciding between materials demands a series of trade-offs: cost, aesthetics, durability, safety, popularity, environmental effects, and social impact, among others. In the coming years, our environment may no longer be able to support the use of conventional materials, so building with things like bamboo or adobe may be necessary. Ultimately, a sustainable material will have several attributes:

- Minimal environmental impact

- Regulated raw material consumption

- Socially responsible extraction practices

- Proper resource management and protection

- Replicable manufacturing processes

- Reduced waste generation

- Resilience to ecosystem shocks

- Aesthetically pleasing

- Affordability

- Accessibility

- Reliability

- Functionality

- Scalability

In the wake of climate change and rapid population growth, it is vital to embrace and advance the use of unconventional materials for housing architecture. Through the fusion of ideas, clever use of local resources, and continued research, we can uncover new materials that are appropriate as sustainable building solutions and for our long-term global needs.

For more on construction materials, please see Building Materials and Methods: E4C’s Essential Online Resources for Professionals.

Further Reading

- Bongaarts and R. Bulatao, “Beyond Six Billion: Forecasting the World’s Population,” in National Academy Press.

- Suffian, R. Dzombak, and K. Mehta, “Future Directions for Nonconventional and Vernacular Material Research and Applications.” Nonconventional and Vernacular Construction Materials: Characterisation, Properties, and Applications, Ed. K. Harries and B. Sharma, in Woodhead Publishing Series in Civil and Structural Engineering.

- Kovach, “Pitt, University of Puerto Rico Engineers Build Upon NSF Grant to Apply Materials Science Research to Bamboo as a Nonconventional Building Resource,” in University of Pittsburgh Swanson School of Engineering Research.

Although we all can agree that more environmentally sensitive materials should be promoted, not all can agree on the GUIDELINES that select one MATERIAL over another IN meeting that goal. Your list above lacks the most important consideration, what material(s) will result in meeting the greatest ENVIRONMENTALLY sensitive outcomes in total if considered applied over a time scale CONSISTENT with CONTINUOUS land use types? How ECONOMICAL is bamboo in wet climates if it hs to be replaced (along with every other part of the structure) every 10 years? Same with cotton insulation. Perhaps this is why we see INCONSISTENCIES in your diagram above where concrete is suggested and ENVIRONMENTALLY sensitive in roofing, and not not in walls. Could any of us really suggest straw bales as insulation in a slum in the Philippines, vietnam, Congo, south aFRICA OR nEPAL CONSIDERING THAT THE LOT IT IS TO BE BUILT ON SHOULD PROVIDE HOUSING SOLUTIONS FOR THE NEXT 200 YEARS?

yOU ALSO IGNORE COMMON SENSE. tHESE MATERIALS YOU SUGGEST AS SOMEHOW “BETTER” HAVE BEEN AROUND A VERY LONG TIME, THEIR USE WELL UNDERSTOOD, INFORMATION AS TO THEIR APPLICATION SIMPLY TRANSFERRED AND ARE UNDER SELECTED BY PEOPLE NEARLY UNIVERSALLY. i REJECT THEY DO SO BECAUSE THEY HAVE SOME UNSTATED DISLIKE OF THE ENVIRONMENT, BUT INSTEAD, ENVIRONMENTALISTS HAVE NOT PROVIDED SOLUTIONS APPLICABLE TO THE SITUATIONS BUILDERS AND OWNERS FIND THEMSELVES IN.