I had the privilege of pitching the obstetric device I’m developing with a team at the University of Michigan at Unite for Sight’s Global Health and Innovation Conference. The experience served as a testing ground for our new ideas and has already opened doors. Our device, called HysTone, can prevent bleeding after childbirth and save mothers’ lives in low-resource settings.

The author, Molly Munsell, pitches HysTone at Unite for Sight’s Global Health and Innovation Conference.

Postpartum hemorrhage, or excessive blood loss after childbirth, is the leading cause of maternal death worldwide, and accounts for 35 percent of maternal mortality in Ghana. Most cases of postpartum hemorrhage are caused by atony, the failure of the uterus to contract after delivery. Atony is routinely prevented using oxytocic drugs that induce uterine contraction. When prevention fails, the uterus must be mechanically stimulated to contract. Providing this stimulus has been approached for many years as an engineering problem. The most common solution in high-income countries is some form of the Bakri balloon, which exerts outward hydrostatic pressure on the uterus.

Balloon systems are inaccessible in low- and middle-income countries (such as Ghana), however, where 99 percent of maternal deaths due to postpartum hemorrhage occur. In these settings, the dominant solution is the improvised condom balloon tamponade, which is assembled on the spot by healthcare workers (demonstrated in the video below). This process leaves much room for error. Also, like the Bakri balloon, the condom balloon is routinely left in place for 24 hours. That required time span poses a greater problem in low-resource settings than it does in well-funded ones due to overcrowding and understaffing in medical centers. There is a need for a postpartum hemorrhage treatment method that is suited for low-resource settings.

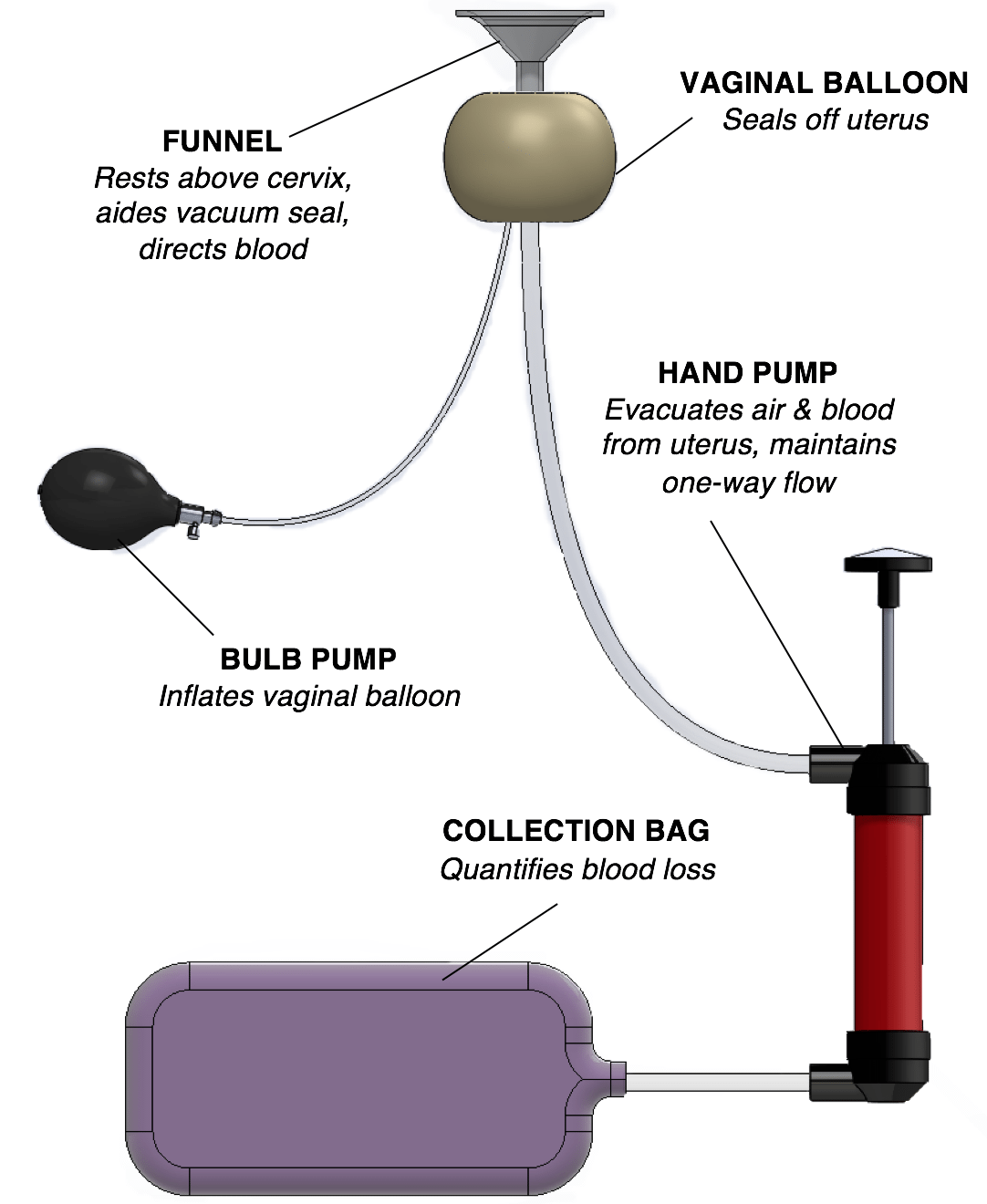

For the HysTone team, which formed through Michigan’s Global Health Design Initiative, this need was assessed at two hospitals in Ghana: Korle Bu Teaching Hospital in Accra, and Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital in Kumasi. Eight weeks of interviews and observations revealed that an improved solution would be non-electrical, affordable, and pre-assembled. Our design was inspired by the Bakri or condom balloon, but we flipped its operating principle. The uterus could be induced to contract with inward, rather than outward, pressure. The only existing postpartum hemorrhage treatment device that uses vacuum pressure is electrical and single-use, thus unlikely to be affordable in low-resource facilities.

The HysTone team includes three undergraduate biomedical engineering students (including myself) and one mechanical engineering student. We set out to design a manually powered vacuum device. Having become very familiar with the word “cumbersome” during interviews with residents and midwives in Ghana, we held ease of use in mind as a key user requirement. The resulting prototype is based on intuitive hand pumps and can be inserted, used, and removed by a single user with minimal training. Uterine contraction would be expected within about 10 minutes during successful use, which is significant reduction of treatment time compared to the condom tamponade. The device is also designed to withstand autoclaving or bleaching, so that a single product can be sterilized and reused, decreasing overall cost to hospitals and governments.

As design iteration continues in Michigan, the HysTone team is exploring avenues for moving forward. The Global Health and Innovation Conference yielded insight on usability and, eventually, clinical testing in Ghana. We are now looking for further advice and partnerships. At scale, we are confident that the HysTone device could provide options and higher-quality postpartum hemorrhage treatment in low-resource settings.

About the Authors

Molly Munsell is an undergraduate student of biomedical engineering at the University of Michigan.

Caroline Soyars is a Contributing Editor at Engineering for Change and Program Manager and Project Development Lead at the University of Michigan’s Global Health Design Initiative.