Residents of the Indonesian community Pandumaan make their living from the surrounding forests by tapping myrrh, an aromatic tree resin valued in traditional and herbal medicine. Recently their livelihood has been threatened, they say, by loggers who are razing the forests for pulp for paper making. To make their case, the villagers hand-draw scaled maps of their lands from GPS coordinates and use them to support legal action against the loggers.

The Pandumaan mappers exemplify a trend in the use of high technology to preserve land and cultures in rural areas. Indigenous sacred sites, burial grounds, caches of medicinal plants and forestry businesses worldwide may have an unlikely rescue from digital tools and satellites. Access to GPS devices and satellite images is increasingly cheap and common, and people are taking notice.

“It’s amazing to see indigenous groups from all over the world coming here armed with hundreds of detailed maps they have created with things like hand-held GPS devices and Internet mapping apps,” Vicky Tauli-Corpuz, who heads Tebtebba, an indigenous peoples’ advocacy organization in Baguio City in the Philippines, said in a statement.

“Mapping not only empowers indigenous communities with evidence that they can use to assert their land rights, it also provides communities with the ability to catalog the natural resources sheltered in their territories. These maps successfully demonstrate what we already know: that indigenous peoples are the best custodians of their forests and lands,” Tauli-Corpuz says.

She helped to organize the Global Conference on Community Participatory Mapping on Indigenous Peoples’ Territories, which took place in August in Samosir on the Indonesian island Sumatra.

Sacred sites and land disputes Representatives from 17 countries heard from other indigenous leaders in Brazil, Mexico, Panama and Malaysia about how new tools are protecting and monitoring their land.

Panama loses more than one percent of its primary forest every year to road construction; new housing, farmlands and pastures; gold mining and logging. The encroachment into rainforests threatens sites that are sacred to the Guna indigenous community. As part of their response, they have mapped the sites in their language, both to monitor incursions and to show their children where to find these culturally important areas. http://rainforests.mongabay.com/20panama.htm

Do-it-yourself maps have also helped indigenous communities in Malaysia win land disputes in courts. Maps have figured into 25 court battles won out of 250 disputes that have been brought since 2001, according to information presented at the conference.

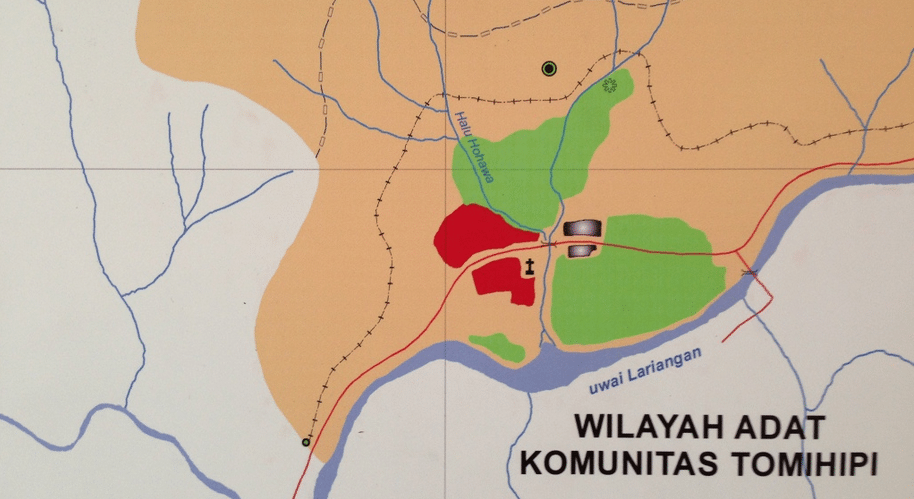

And in Indonesia, home to 50 million indigenous people, maps bolster a call for special laws to protect against incursion from palm oil companies, loggers and other industries. [quote author=”Giacomo Rambaldi – senior program coordinator Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation”]Without maps, it is difficult for indigenous peoples to prove that they have occupied their ancestral lands for centuries. [/quote]

“If you are able to document and map your use of the resources since time immemorial, you have a chance of asserting your rights over land and water,” Rambaldi says.