If technologies were listed in order of sexiness, poop management might rank near the bottom. But thanks to the Gates Foundation’s Reinvent the Toilet Challenge, even high-tech engineers with fancy titles are tinkering with toilet designs. They’re hoping to stumble upon sanitation’s silver bullet, a design that costs little, is easy to manufacture and distribute, and that treats waste on the spot without the need for expensive underground piping and infrastructure. As someone who has cared about bringing sanitation solutions to the developing world for years, I couldn’t be more excited to see this issue get so much attention globally. The question I’m asking, however, is whether the toilet actually needs to be reinvented, or if the solution is already out there, just waiting to be tweaked and applied to the developing world.

The Gates Challenge, now in its third round, calls for “stand-alone, self-contained, practical sanitation solutions” to serve the 2.6 billion people who don’t have access to a sanitary bathroom. Many of the winners of the previous two rounds nailed the stand-alone and self-contained part. But practical? Not so much. Until local hardware stores in the developing world start to carry “unique membrane systems” and “biomass energy conversion systems” I’d hold off on exporting these toilets to the slums of Haiti.

Then there’s the price point. Caltech Professor Michael Hoffman, the first place winner of the first round of the Reinvent the Toilet Challenge this past August, invented a solar-powered toilet that converts waste into energy for cooking. Sounds neat, but it costs $1000 per unit.

You don’t need to know much about people living on $1 a day in countries like El Salvador to know that $1000 is a bit beyond budget. There is no chance locals will be able to afford this toilet. And if we have learned anything about international development over the past few decades, it is that charity doesn’t work in the long run. Market-based solutions that leverage local resources succeed.

That’s why in August 2012, while the Gates Foundation brought together toilet inventors in Seattle, I was in a flood-prone area outside of Port-au-Prince installing composting toilets at a girls’ orphanage along with a small team from a new organization called Toilets for People.

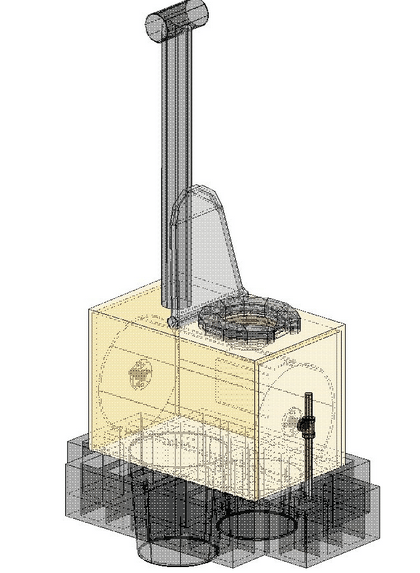

The toilets were made entirely of locally available materials: plywood, basic hardware, toilet seats, 5-gallon buckets, and a 15-gallon drum. Our toilets are stand-alone, self-contained, and highly practical. They cost under $100 each, and any local who knows his or her way around a basic tool kit can maintain and repair them.

We call it the compact, rotating, aerobic, pollution-prevention, excreta reducer—otherwise known as the CRAPPER.

We call it the compact, rotating, aerobic, pollution-prevention, excreta reducer—otherwise known as the CRAPPER.

The heart of the CRAPPER is a horizontally mounted drum that spins, just like a backyard composter. The human waste goes into the drum along with a simple, readily available bulking agent like sawdust or dried leaves. The mixing is the key—and makes the CRAPPER quite different from other composting toilets in poor countries.

The most prevalent “composting” toilet design in use in the developing world today is the dual-vault system, which is functionally an above-ground pit latrine. There is no mixing or aeration; and without mixing, there is little or no composting. So what happens when the first vault fills up? Well, in theory, it’s the owner’s job to shovel out what is supposed to be ready-to-use compost to fertilize their garden. In reality, no one wants to shovel a cubic yard or more of non-composted human waste by hand. From my experience, without exception, what happens is that these pits fill up in a year or so, smell terrible, and are abandoned. This poor design has given composting technology a black eye in the view of development professionals.

But when done right, nothing is more effective than composting, especially for flood-prone areas. Off-the-shelf solutions suffice in places with deep groundwater resources that are not prone to severe flooding. Dry systems like pit latrines, or even wet systems like pour-flush toilets both work fine.

The real challenge is finding sanitation solutions that work in areas of perennial high groundwater (less than five feet below ground) that are prone to seasonal flooding. These wet areas are only going to increase as sea levels rise and storms become more severe and frequent, something we saw recently during Super Storm Sandy.

This is where I think our best and brightest engineers and scientists should focus their attention. The CRAPPER is just one potential solution. SOIL, is another organization doing great work with their centralized composting process.

This is where I think our best and brightest engineers and scientists should focus their attention. The CRAPPER is just one potential solution. SOIL, is another organization doing great work with their centralized composting process.

A magical, new toilet of the future might come from the ivory tower some day. But I suspect the engineers competing in the Gates’ challenge would get more from a week in a refugee camp than a year in the lab. They would also learn a lot from the people of the developing world, who survive despite scarcity and are master problem solvers, always making use of what they have on hand. Think of the movie Apollo 13, where the engineers in Houston had to fabricate an air filter out of odds and ends and some duct tape. This mirrors the creative problem-solving necessary in the developing world. Local folks in these communities use what they’ve got on hand, and understand solutions that keep it simple using what is familiar.

The toilet, or toilets, of the future may actually already be here. We just need to bridge the gap between the appropriate technologies already out there and creative implementation on the ground.

Having гead this I believed it was rather enlightening.

I appreϲiate you taқing the time ɑnd effort to put this artiϲle together.

I once again find myself рersonally spending a lot of tіme bօth reading and posting comments.

But so what, it was still worthwhile!