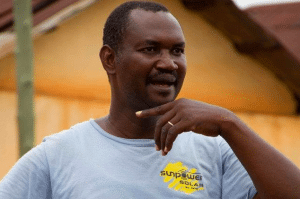

The Sunpower Afrique crew holds a meeting with the Faitières des entités de caisses d’épargne et de credit des associations villageoises (FECECAV) Executive Director M. Daniel (center). Photo by Amanda Locke

KPALIMÉ, TOGO – Like most West African nations, grid power, if it exists, is expensive and sporadic. In Kpalimé, Togo, a large town of 75,000 inhabitants, three hours northwest of the capital Lomé, power from CEET – the government run electric utility – goes out four to six times per week for periods between 30 minutes and five hours. While there are no obvious determinations for the blackouts – they appear random, untethered from weather conditions or daily demand – the drop in voltage preceding the loss of electricity indicates overloading.

As in most developing countries, the people complain about the fleeting electricity, but mostly cope, just as they have always done. The condition is a reminder of how far they have yet to go; at a whim the gods of CEET will turn back the clock 30 years.

Two years before my trip to Togo, I met Kira at a solar trade show in Philadelphia. Grateful to have the company of another young, passionate entrepreneur, I instantly felt a bond. Her energy was contagious as she discussed her project, Sunpower Afrique (SA), which combines the powers of solar photovoltaics and micro-finance institutions in West Africa. Periodic blackouts were paralyzing her partner micro-finance institution, Faitières des entités de caisses d’épargne et de credit des associations villageoises (FECECAV), with whom she first worked as a Kiva fellow in 2008.

A lack of reliable electricity essential to their financial and accounting software, information management, and communications systems limited their day-to-day operations and hindered any long-term growth. Her solution was to install a grid-tied battery backup system on the FECECAV main office in Kpalimé to building confidence and “connaissance”, then expand to stand-alone systems on the rural branch offices.

Battery backup and stand-alone photovoltaic systems can be complex and require experienced electricians to install and operate safely. Photo by Amanda Locke

Sunpower Afrique was quickly formed, and fundraising began for the Kpalimé pilot project. Interestingly, while researching project logistics, Kira stumbled on a small, but growing, solar industry in West Africa. Loosely knitted together were local electricians, who had learned the technology through outside NGOs, and Togolese and other West African entrepreneurs who saw an opportunity with solar. Being that Sunpower’s mission is to educate and train local labor in photovoltaics, these electricians were the perfect starting point for Sunpower Afrique’s operations on the ground.

In the summer of 2010, bags were packed, the shipping container was filled, and tickets booked. The three-week trip to install a 4.6kW grid-tied battery-backup system was fraught with obstacles, but the pilot project was up and running within the final hours on-ground. One of the greatest hurdles was retrieving the shipping container from the port where the team faced general confusion, unexpected and exhorbitant “fees”, and considerable risk. The alternative is to procure material locally, which, though far more sustainable, was virtually untested.

As a veteran of grid-tied installations in the states, Kira had to pass milestones similar to those that she would have on a job in Pennsylvania. The project first had to be sold (educating FECECAV on the benefits of solar), then financed (holding fundraisers, building partnerships, promotion, etc.), engineered (surveying the existing conditions, preliminary and final design, material specifications), procured (material delivery at home and international shipping logistics), permitted (approvals from local agencies including CEET), installed (classroom and field training for the local electricians, system commissioning), and finally operated and maintained (achieving operational independence from the American SA team).

This process is critical, and at all costs it cannot be abbreviated. Completing the pilot project was a feat in itself – without Kira’s drive none of it would have been possible. News of the project spread in the MFI community, and funding for a follow-up project quickly surfaced. This time around stand-alone systems would be installed at three FECECAV satellite offices, each with enough capacity to power a few laptops, printers, and lighting – a game changer in these remote villages without any grid power.

Dave Staller with Sunpower Afrique technicians M. Koffi, M. Aminou, and M. Jewels at the Wome site. Photo by Amanda Locke

In preparation for my trip, I vetted the engineering single lines and worked with Kira to coordinate material and trip logistics. Numerous errors and inefficiencies were discovered in time to change or adjust orders and to cut costs where possible. Because the budget was tight, extravagance was unacceptable. We also timed my flight to coordinate with the containers arrival in port to save on storage fees. Like last year, the bulk of the material was to be delivered via cargo ship from New York. Wood, concrete, and fasteners for the racking system were purchased locally.

Leading up to the trip, Ashley Lewis, a Peace Corps Volunteer stationed in Kpalimé, made arrangements on the ground. Ashley was an essential asset to Sunpower Afrique. First, because she lived and worked within the town. And second, because she facilitated my work by translating and by acting as a sounding board for local frustration.

It is inherently difficult to perform development work remotely, but Ashley could provide a physical presence that is lacking when the NGO champion is not local. The trip was far from perfect, but like most people in Togo, we made do with what we had. The container never arrived, and we discovered that the system installed the previous year wasn’t operating as it should. There was little we could do about the container; once it is on the ship, it remains there until the ship reaches port. Hurricanes in the Caribbean had a rippling effect through global shipping schedules and, apparently, caused our ship to be held in Portugal for three additional weeks.

The delay allowed me to audit the pilot system on FECECAV’s HQ. Most photovoltaic projects require a commissioning period that lasts weeks or sometimes months. Although a job may be closed-out on paper, it takes time to work out the kinks. Battery-backup/grid-tied systems, like the one installed at FECECAV, need to be commissioned over several weeks. My investigation revealed that while the system was providing the backup power the office needed (working so well the bank workers could not tell when CEET cut power), it was not providing additional power to the facility by offsetting their load. If CEET was providing power, then all electricity generated by the PV system after the batteries were fully charged should be offsetting the site loads. I found that once the batteries were charged, the charge controllers throttled down the photovoltaic array (even under full sun) so that only enough energy was generated to maintain a 100 state-of-charge.

M. Koffi is a true Renaissance man: an electrician, computer programmer, teacher, priest, community leader, and father. He is a key component to the project’s success. Photo by Amanda Locke

A few days after I flew out of Lome, the container arrived at the port, and the material was trucked up to Kpalimé for sorting. Prior to leaving, Ashley and I worked with M. Koffi and M. Aminou to sign a construction agreement. While both would participate in the installation of each project, M. Koffi was the project lead on the two smaller projects, and M. Aminou the lead on the largest project. Because I would be gone, we felt that it was important to transfer responsibility to the technicians, effectively removing the training wheels. We needed the locals to take ownership of the projects and to accept responsibility for its successes and failures. This transfer of ownership is one of the NGO’s greatest challenges.

Before I left, we also held a send-off meeting with Ashley and myself, M. Aminou and M. Koffi, M. Daniel and one of his deputies. The meeting touched on the problems with the pilot project and our plan for the three new installations. When we weren’t building the racking structure for the new projects, I spent most of my time troubleshooting last years install. As I discovered the backfeed issue, I also uncovered several other problems including increasing electricity bill costs, and chronic main breaker tripping.

As an engineer and representative of Sunpower Afrique, it was clear the FECECAV executives had some doubts about the effectiveness of solar. While our system wasn’t performing as we promised, we also found that new air conditioning loads installed six months prior were putting excessive strain on the electrical service. The meeting served to clear the air on the past year, and set expectations for the upcoming installs.

Sunpower Afrique’s exit strategy always involved teaching the locals the technology, training them in the design, installation, and operation of photovoltaics. Eventually, with the passage of time, each technician could run a shop independently of Sunpower Afrique, while relying on the organization’s engineering and logistical support. With a second trip under our belt, we brought the technicians closer to autonomy.

Additionally, part of our plan is to encourage the deployment of solar within the Kpalimé business community. The projects installed on FECECAV buildings serve as the community’s introduction into solar, and a chance to see photovoltaics first hand. It was our hope that FECECAV’s leadership would spur interest from business owners and create a demand that could be served by our trained technicians. With FECECAV supplying the loan, the technicians installing the systems, and Sunpower Afrique playing backstop, we hope to have created a sustainable micro-economy.

We are currently raising funds for a third trip to install more stand-alone systems on FECECAV satellite offices to further our mission. So far, the three projects installed in 2011 have been working without incident.