In a Huichol community in the Sierra Madre range of western central Mexico, Sheila Kennedy (2nd from left) and Stacy Schaefer, an anthropologist (left), show Estella Hernandez (2nd from right) how to use a Portable Light solar textile. Photo courtesy of James Bauml

The head of a program that is equipping off-grid communities with solar power-generating textiles suggested that the technology might represent an emerging shift in infrastructure. We reported on the work of the Boston-based program, called the Portable Light Project here. To venture a little deeper into the ideas behind the idea, we’d like to share notes from an interview with Sheila Kennedy, head of the project and senior principal at the Boston-based firm Kennedy & Violich Architecture, Ltd.

E4C: You’ve said that portable light can redefine the energy problem in the developing world. How does it do that?

SK: I’d emphasize that design has a role to re-define what a given problem really may be. Lack of affordable access to energy is certainly a highly visible part of the problem, but it’s not the only part. The problem also includes carbon emissions and the gray energy that is consumed in making and shipping clean energy products. A material science dilemma emerges when the manufacturing of energy consumers more energy than it initially produces. If contemporary industry manufactured only silicon solar cells, a significant increase in carbon emissions would result before ‘clean’ energy could be recovered. So, the larger problem encompasses catalyzing a change in our culture of materials, and the ways in which they are manufactured.

E4C: Tell us more about soft infrastructure and the flat-to form fabrication process

SK: As an architect, I try to understand as much as possible about a given problem, and imagine how the terms of that problem could change if one thinks differently about assumptions. With thin-film photovoltaics, energy technology becomes material. And what is material is also technology. The implications for design of this new configuration of energy and matter are significant. We can imagine what the unique properties or advantages of might be for a flexible energy material. We can then imagine and design portable light kits as an adaptable soft infrastructure for distributed energy and lighting. We’ve thought a lot about this, and developed a flat-to-form design process, which can scale from industrial design to architecture. A three dimensional, reflective lantern form can be designed and then flattened into a flat pattern which can then be cut from local materials using simple techniques like sewing and weaving. When you bend or fold that pattern, it literally pops up into a lantern form—light weight, low energy, highly adaptable and co-created locally so it builds local businesses. The flat-to-form idea is very simple, but it represents a big departure from singular, hard designed objects, which is what so much of typical industrial design is—all that plastic and glass, all that embodied energy.

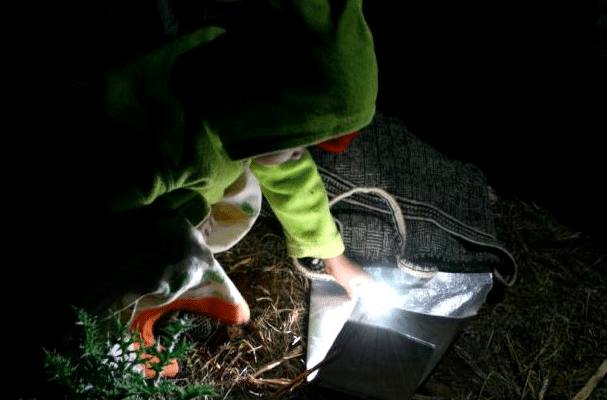

A girl from the Huichol community examines an LED lantern charged by a solar textile. Photo courtesy of Kennedy & Violich Architecture, LTD.

E4C: What are some examples of how the solar panels have improved lives?

SK: A woman can add to her family income significantly with renewable light and the ability to charge a cell phone. In Nicaragua, with the non-governmental organization Paso Pacifico, there are many examples of how women are organizing to run eco-tourism businesses with education and literacy programs. Women have become conservation rangers. They charge their portable light by day, and they have designed a portable textile that detaches from their conservation bags and serves as a lantern at home for literacy programs, children’s education and household chores. In the amazon in remote river communities where we are working, local beekeepers and women’s cooperatives want to use portable light to grow their businesses because it provides portable energy and light anywhere in the forest or on the river ways.

E4C: What would you recommend about your open source model to others who are trying to distribute their devices?

SK: We’ve produced a simple solar textile kit which is adaptable, and that has been valuable. There is so much over-specified stuff out there— do we really need another cheap plastic gizmo? Instead, we need a system that is enduring, resilient and versatile. Think about how to balance what is specific with what is general. Portable light has a dedicated application–light—and a USB 2.0 platform that is an energy ‘throughput’ use, which is versatile. Think about how your project is manufactured, how to lower the carbon. Think about the changing culture of materials and how to tap into that, no matter how crazy at first that might seem. [Portable light] is a new material culture, not just a miniaturized version of our historically modern way of using electricity.

E4C: Where do you plan to take this project in the future?

SK: The portable light team is interested in the emergent energy-water nexus. We’re experimenting with mobile water monitoring systems and cell phone apps that can be powered with the portable light USB port. The project is expanding in the Amazon region and we’d like to work with NGOs and partners in coastal areas for ocean and river water conservation. We’re looking for innovative partners who can assist with low cost soft packaging, and techniques to up-cycle local (discarded!) plastic materials. Our goal is to work with NGOs to expand our open source portable light renewable conservation toolkit and bring it to more communities in endangered coastal areas.