Medical device innovators pulled off a coup at this year’s Innovation Showcase, taking all of the top prizes at the American Society of Mechanical Engineers’ annual design competition. Three collegiate teams won awards of $3000, $5000 and $10,000 in seed money to help take their prototypes to market. In this article, we present the third-place finisher, the autologous blood transfusion device, by students at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

Hand-pumped blood transfusion

As blood pools in patients’ abdominal incisions during operations at Ghanaian hospitals, surgical teams spoon it out with a soup ladle. Then they pour the blood through gauze to filter out clots before transfusing it back into the patient. While the improvisation saves lives, it is a clear target for improvement.

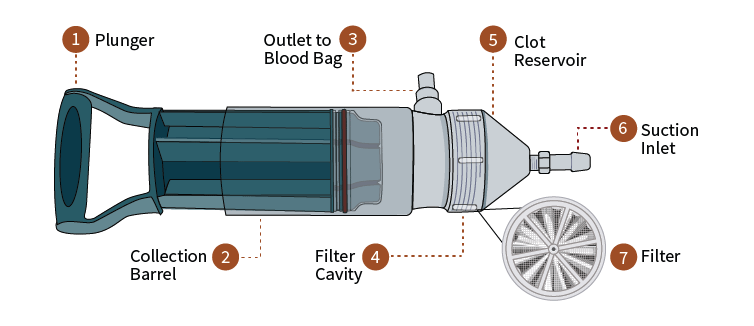

Students at the University of Michigan came to that conclusion during a fact-finding visit to Ghana last year. The students, who call their team Design Innovations for Infants and Mothers Everywhere, believe they have a solution: a hand-pumped autologous blood transfusion device. The device looks something like the offspring of a bike pump and huge syringe, with surgical tubing affixed to its head for incoming and outgoing blood. It draws blood into its cavity, passes it through a disposable filter, and pushes it out for transfusion.

Is it better than a soup ladle?

Probably. The device should save time and improve hygiene. It saves time by freeing up medical staff to do other work. The soup-ladle method requires three or four healthcare workers to scoop and filter blood. Just one person can operate DIIME’s device. The device may also be safer for the patient because it is simple, enclosed and user-friendly. Future clinical tests may bear that out.

The advantage of the ladle, however, is that it is cheap. DIIME has tried to keep the cost of its device low at $300. The team recommends disposing of it after 50 uses because its medical-grade plastic parts can deteriorate after a few dozen rounds of sterilization in the autoclave. The cost breaks down to $6 per use, Malvika Bhatia, co-founder of DIIME, points out. That, she says, may compete favorably with the soup ladle when you factor in the savings in man power.

James Akazili, an official in Ghana’s health ministry, inspects the prototype of DIIME’s transfusion device. Photo courtesy of DIIME

When do patients need transfusions of their own abdominal blood?

During emergency surgery to repair ruptured ectopic pregnancy, especially when a well-stocked blood bank is not on hand. Sometimes, when a human egg is unable to pass freely through the fallopian tube, a pregnancy occurs outside of the uterus. The embryo most likely cannot survive in these ectopic pregnancies, and if it develops, it can kill the mother. About half of the time, the woman’s body dispatches with the embryo on its own. In other cases, the woman needs medical attention.

Developed countries have an array of diagnostic tests to detect such pregnancies, and ample treatment options ranging from drugs to surgery. Not so in many developing countries. When an ectopic pregnancy goes undetected and ruptures, surgeons must repair the damage. Patients lose blood and need transfusions during the operation. Even with access to a blood bank, it is sometimes preferable to transfuse a patient’s own blood from the wound back into the body. The procedure can reduce problems with blood-type matching, infection and others.

Ectopic pregnancy occurs in 1 to 2.5 percent of pregnancies worldwide. It is a leading cause of maternal death in the first trimester. And while the condition accounts for only 0.5 percent of maternal deaths in Africa and Latin America, it competes in a grisly field against bigger causes of death such as sepsis, HIV/AIDS and hemorrhage. Also, patients in a broad geographical area can be concentrated into a few healthcare centers. Two Ghanaian hospitals that DIIME visited performed more than half of the ectopic pregnancy surgeries in the entire country.

Are there other uses for the device?

For now, DIIME is targeting this one procedure, but the device may serve in other abdominal surgeries, Bhatia says. It may also be useful to first responders or even military medics in the field, but that’s conjecture for now.

What’s next?

The device is due for clinical tests next year. The team is putting it through pressure tests now to find out if its suction destroys blood cells. In the meantime, the device has impressed experts in the United States, helping DIIME scoop up a handful of grants and prizes, including a third-place award at IShow on June 11.

This Is GREAT, I WANT TO Research It IN MY Hospital, IN Tanzania. How Can I COMMUNICATE With You….

Thanks