Mario Cucinella Architects and WASP, an Italian 3D printing enterprise, announced that they began printing housing prototypes called TECLA. The operation began near Bologna, Italy, with crane-mounted printers laying down layer upon layer of a mixture made from sand and soil in the region. Although this first attempt is in Italy, the plan is to create a model that can be replicated in any region worldwide.

The housing is circular, printed with locally sourced clay on top of a concrete footing. The design and construction method represent the two firms’ solution to housing shortages that are expected to worsen as the world’s population approaches a projected 11 billion in 2100.

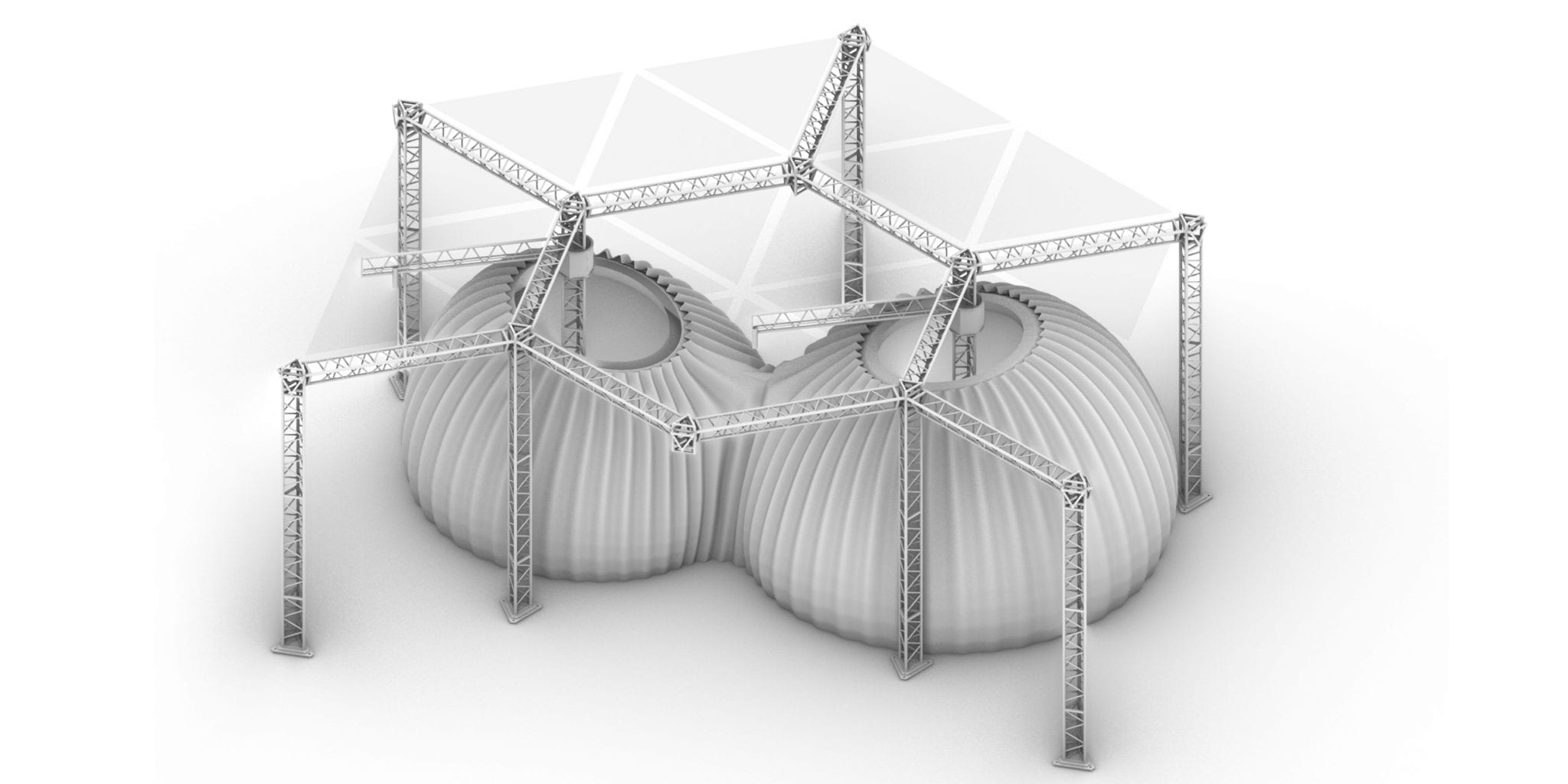

TECLA will be the first habitat to be built using multiple collaborative 3D printers, offering a greater scope of scale than ever before.

“With more and more rural areas being incorporated into cities, it is the idea of city itself that must be challenged,” MC A and WASP say in a statement. “TECLA will be the first habitat to be built using multiple collaborative 3D printers, offering a greater scope of scale than ever before. Used in the context of a wider masterplan, TECLA has the potential to become the basis for brand new autonomous eco-cities that are off the current grid,” according to the statement.

TECLA 3D Printed Habitat ©Mario Cucinella Architects

The printed homes are intended to find a niche in the circular economy of the sustainable use and reuse of local, recyclable materials. If the buildings perform like earthen brick construction, they may reduce the need for heating and cooling through the material’s natural insulation that regulates indoor temperatures.

See Five Questions for Jim Hallock, Expert in Compressed Earth Block Construction

The domed shape of the printed houses is designed to adapt to many environments, providing more energy efficiency than traditional housing. Consulting firms have supported the construction of the prototypes, optimizing the content of the clay for printing and performing structural tests on the domed design.

These guys have been at it for a while and it shows.

No timeline has been announced for commercialization, but the companies gave a clue about one way they may scale the project. Communities or enterprises may be able to build their own using kits that WASP has developed.

See E4C’s Solutions Library for housing solutions

“These guys have been at it for a while and it shows,” says Charles Newman, an architect, founder of Unfrastructure Design and Expert Research Fellow at Engineering for Change in 2019. “Their design looks to be very well developed and much closer to achieving 100 percent local materials,” Mr. Newman says. He did have questions about some of the claims, and MC A responded.

A Crane WASP 3D printer prints an earthen wall of a TECLA housing prototype.

100 percent locally sourced may not be possible

Locally sourcing every material for printed homes may be difficult to manage, given the need for concrete slabs as a foundation upon which to print, Mr. Newman says.

In a statement to Engineering for Change, MC A responded that the foundations do indeed require concrete. It may be noteworthy to mention that most earthen construction calls for some cement, if not for foundations then to add water resistance to the soil mixture. Although lime and other materials can be used as well.

“The foundation system envisaged for TECLA, as already tested in the case of Gaia, consists of a network of 3D-printed formwork through a cement mortar, easily replicable on each construction site. The pouring of concrete inside the formwork, articulated according to the architectural project, allows for the minimum use of concrete in the foundations, making it possible to construct the laying walls through 3D printing. The use of cement mortar in foundations is due to the greater resistance over time and compatibility with the cast concrete,” MC A says.

Earthen construction requires regular maintenance

Without support, earthen construction disintegrates in the rain. All compressed earth block structures need regular maintenance, Mr. Newman says. That includes the annual application of a sealant to provide moisture resistance.

“Even the best mixture of clay is subject to erosion over time. This design presents no coverage from rain (all wall no roof), so it would be great to hear their thoughts to protect against such effects,” Mr. Newman says.

MC A responds that the structures do indeed require the application of a moisture-resistant spray.

“The protection of raw earth masonry against atmospheric agents is achieved through the surface spray treatment of a waterproofing product, supplied by Mapei, partner of the TECLA project. The protection takes place thanks to the hydrophobic characteristics of the product and the high penetrating power which make the surface very resistant to any atmospheric agent.”

The need for the spray reduces the percentage of local material usage. Supplying the proprietary spray, or something similar, may become an obstacle to the viability of these buildings in remote regions with poor road access, and even in urban areas without established supply chains.

Soil composition matters, and it changes from region to region

The soil used in earthen construction must have certain ratios of clay to sand to cement or lime as a hardener. And soil composition differs on each construction site.

For more on earthen block soil composition, see: A new digital tool takes the guesswork out of making compressed earth blocks for construction

“They say the design can be adapted to any climate, but isn’t it totally dependent upon the content of the soil? Could mixtures be crafted when printing in a rain forest for example? With rich organic soils?” Mr. Newman asks.

In reply, MC A says the soil will be evaluated at each site.

“The chemical/physical composition of the soil is analyzed at each construction site and, based on the primary components, a mixture suitable for the 3D printing phases and able to achieve adequate construction performance is optimized. The organic fractions of the soil are not part of the mixture because they are a source of chemical degradation and are excluded from time to time in the soil removal phase,” MC A says.

Soil analysis equipment and expertise, plus the additional sand, clay or other materials needed to optimize the soil for printing in each region, may be another hurdle in a worldwide rollout of 3D-printed housing.

How to scale up 3D-printed housing?

In considering how TECLA homes might scale up, Mr. Newman raises issues of labor and the time it takes to build each home.

WASP’s unique 3D printers can cut the time and labor required, MC A says. But the specifics of how to scale up are still under study.

The first prototype aims at exploring the possibilities of a fully 3D-printed envelope, but the combination of other technologies and materials will generate new scaling up opportunities

“The opportunity to scale the objects is currently a field of research for TECLA. The first prototype aims at exploring the possibilities of a fully 3D-printed envelope, but the combination of other technologies and materials will generate new scaling up opportunities. The advantages deriving from the Crane WASP 3D-printing system, which is used for TECLA, allow a significant reduction in terms of manpower and construction times, due to the performance of 3D-printed constructions, both in terms of thermal insulating and minimum environmental impact,” MC A says.

A credible bid for sustainable 3D-printed housing

TECLA is in an early stage. As with any prototype, it raises questions. How likely is the potential for scale, for example? And can they really create a design and a system that uses 100 percent local materials, or something close? Thus far, however, TECLA appears to be a credible shot at sustainable, scalable 3D-printed housing. Compared to attempts by other companies that Mr. Newman looked into during his Research Fellowship, TECLA may be the first that has come this far and this close to real sustainability.

For more, please see: MC A’s page on TECLA | WASP’s page on TECLA