Higher education in Tunisia lags in attracting young students and fails to retain skilled individuals who can contribute to the development of their homeland. Like many other Tunisians, I chose to pursue higher education in Europe and eventually started working there. The situation is improving, but more opportunities at home in Tunisia are needed for higher education students. Especially in the areas of social innovation and entrepreneurship.

While living in Europe for more than a decade, I had almost forgotten about a picture I had taken seven years ago of a school under construction in rural Tunisia. I had visited the area while leading a program founded at my university in France.

The photo represents the poor state of schools in rural areas of the country. Between bricks and stones, hundreds of young kids struggle to catch a glimpse of education. Although all children starting at age six must go to school in Tunisia, whether they are able to get a proper education or not is a burning question.

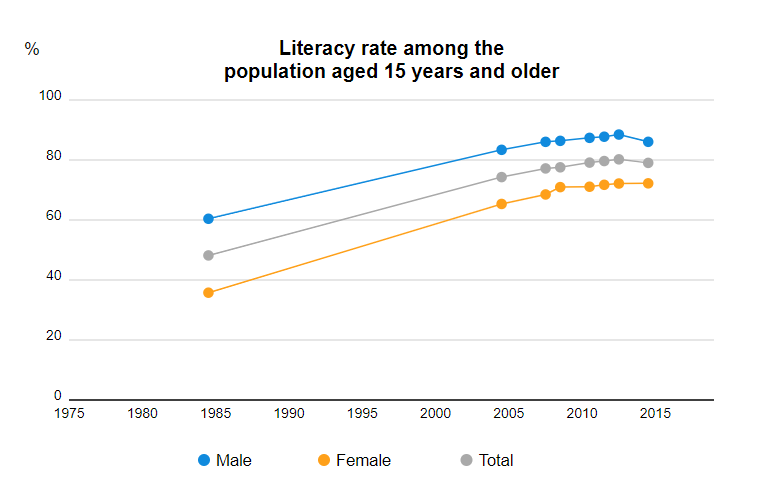

Source: UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS)

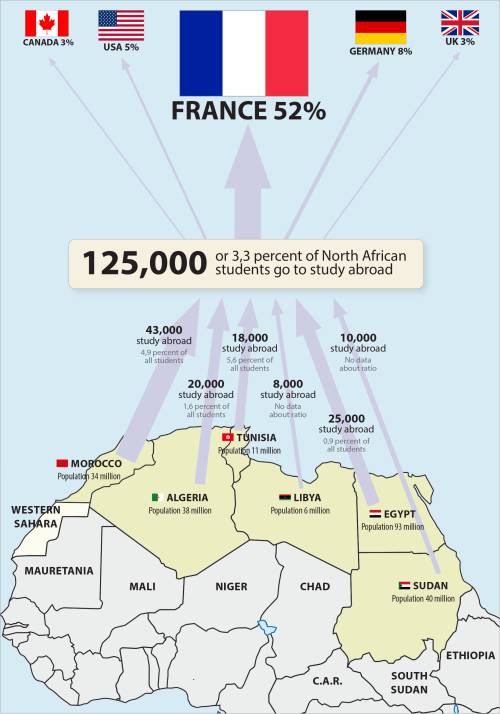

Despite the progress made on literacy rates in Tunisia, according to statistics from UNESCO, dropout rates are still high. Dropouts are especially prevalent in the border regions where parental illiteracy, poverty and poor infrastructure prevent children from pursuing their education. Another phenomenon is the emergence of private schools alongside public schools, a model highly influenced by the French, who formerly colonized Tunisia. The trend reflects parents’ distrust in the public school system. The lack of opportunities and the shadow of youth unemployment darkens the perspective of higher education in North Africa and specifically Tunisia. According to this article from the Nordic African Institute, 3.3% of students from North Africa choose to pursue their higher education in Europe and 5.6% in Tunisia alone.

This academic flight from Tunisia has been characterized as brain drain, or “the migration of highly skilled and educated people,” according to a paper from the United Nations Expert Group Meeting on International Migration and Development in the Arab Region. Different programs and enablers such as scholarships and grants support and encourage this migration, as universities in developed countries work on attracting those young skilled students. In an elite high school, getting a scholarship was, and still is, the incentive for many students to seek better work opportunities.

Source: Henrik Alfredsson / Nordic Africa Institute

I was awarded one of those scholarships after high school to pursue engineering studies in France. This scholarship is given to approximately 50 young students every year and fully covers the expenses of their master degree in Engineering either in France or Germany. The hope is that one day these newly trained individuals will return to their home country to participate in its development. However, what often happens is that they stay abroad. North African students look for jobs in Europe after graduating and settle down there. Counter-initiatives are now emerging to stop the migration of students, but do not address the core issues behind this phenomenon. Other more encouraging initiatives are those linked with promoting social innovation and supporting startups and young innovators, which is further enhanced by the Startup Act passed by parliament in 2018.

Despite the Brain Drain, there are still opportunities to give back to Tunisia. I took the picture of the schoolhouse above when I came back to Tunisia with a group of international students to distribute school supplies. Looking back at this picture, I wonder what happened to the school. Did the encounter with young engineers from abroad inspire those children to continue their education? What happened to them? Did this small student-led project participate in the development of children in my home country? Even if there were efforts to bring back some of the valuable knowledge gained in Europe to contribute to the development of Tunisia, there are still some gaps to have a sustainable impact on the country’s development.

It has been seven years since I took this picture. I am now working as an engineer in one of the biggest companies of the world and still living in Europe. The opportunity with the Engineering for Change Researrch Fellowship is helping me explore the impact an engineer can have. I am again looking forward to having a positive impact and to participating in the development of my home country. I have a lot of ideas and also a lot of questions. Now, how can young engineers help in the development of their home countries? Social innovation and entrepreneurship might be an answer.

About the Author

Khaoula is an E4C Research Fellow from Tunisia and currently lives in Hamburg, Germany. She works as a Customer Provisioning Support Manager at AIRBUS Operations. She graduated as an aeronautics engineer in France after having an exchange year of studies in Germany. She has been working for five years in the aerospace industry, starting as a young engineer at AIRBUS Helicopters and working in the field of System Engineering and Airworthiness. She recently joined AIRBUS operations to work as a Program Manager in the field of customer support and services in Germany.

Well articulated!