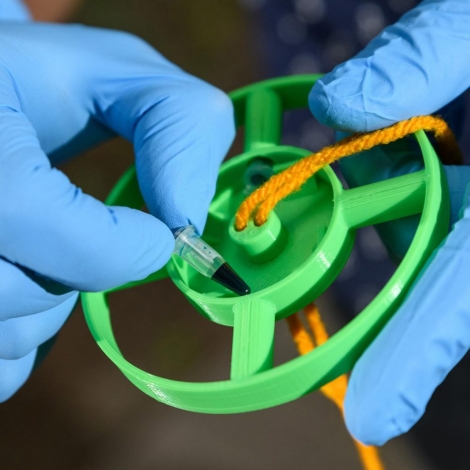

A Georgia Tech professor teaches students to make intuitive, low-cost instruments for people in developing countries. Photo: Rob Felt, Georgia Tech

Engineers are certainly not new to developing low-cost equipment for use in places where electricity is as rare as expensive equipment. But those solutions aren’t necessarily “frugal,” said Saad Bhamla, a Georgia Tech professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering, who is dedicated to the science of frugal engineering.

“You’d have a problem putting some of those things in your pocket. They may not perform as well as more expensive equipment and their parts may not be easy to get,” he added.

Simple devices that work in the field but rely on a smartphone to act as a sensor or to track information don’t meet Bhamla’s frugal-engineering definition.

According to Bhamla, the principles that define frugal engineering are high performance, low-cost, easy access, and very portable. His lab is partially devoted to frugal science, a term he and his colleagues coined while working on their postdoctoral research at Stanford University.

The Origin

Bhamla traces his present-day research to his time at Stanford, specifically to a paper centrifuge that he helped develop while working under Manu Prakash, a physical biologist at Stanford University.

The Stanford team knew centrifuges were hard to come by in developing areas, where doctors need them to diagnose diseases, include malaria, tuberculosis, or HIV. The centrifuge is bulky, costs between $3,000 and $4,000, and runs on electricity.

But they are always needed.

“From extracting plasma from whole blood to analyzing the concentration of pathogens and parasites in biological fluids such as blood, urine, and stool, the centrifuge is the workhorse of any medical diagnostics facility,” Bhamla and his fellow researchers wrote in a paper published in the January 2017 edition of Nature Biomedical Engineering.

The cost and accessibility problem wasn’t new. Engineers had been working on a cheap substitute that could act as efficiently as their much more expensive cousins. These versions used egg-beaters or salad spinners for rotation. But they were bulky; they couldn’t fit in a pocket; and they had extremely low rotational speeds, which made for an impractically long time spent spinning samples, said Bhamla.

Prakash’s team was inspired by the whirligig, a toy made of circular disks that are spun by pulling on strings that pass through their center. Their creation, the Paperfuge, is also comprised of disks that are pulled and spun by string or, in this case, wire.

The Paperfuge is made from cardboard, fishing wire, and PVC pipes. Small plastic tubes filled with a sample are glued to the disk and rotated. Bhalma and colleagues reported that the Paperfuge separated pure plasma from a blood droplet in less than 90 seconds.

And it fits in a pocket, for easy transport into the field.

Bhamla hopes seeing it used may inspire a nonengineer to create another type of frugally engineered device.

“I want to empower others to make their own stuff,” said Bhamla. In fact, he worked with high school students to make the 3D-Fuge, a 3D-printed version of the Paperfuge.

Getting Down to Cents

The idea of riffing off current designs to find frugal solutions got him thinking. Could he, as a professor, convey the principles of frugal engineering to get others inspired?

The answer is yes.

Often, “something is right in front of you, like the whirligig. And then it’s a matter of whittling away at the problem in increments,” Bhamla said. “Or sometimes it’s finding a whole base element and then finding ways to reduce costs by using a mechanism that costs pennies to generate needed physics.”

Many efforts begin with a question. Like, why is a hearing aid so expensive?

They cost around $5,000 and aren’t covered by health insurance in the United States. As a result, people nudge a failing hearing aid along for years or even go without one.

Bhalma’s team is now developing a hearing aid that would cost less than a dollar. The device could help millions of people and the lab has received grants from the NSF, Mindlin Foundation, Capita Foundation, and National Geographic Foundation.

Of course, Bhamla is aware his lab is not the only one on the frugal engineering path. Whether it’s a community of scientists or students or actual users, “someone is thinking about this problem,” he said and believes that sharing ideas will push efforts farther and faster.

“It’s always nice to not be working in a vacuum,” he said. “Because other people are working on the problem, I see ideas and things that students bring to me. That’s very useful.”

Pushing frugal engineering efforts farther and faster has become somewhat of a mission to Bhamla; a mission that may benefit millions of people.

About the Author

Jean Thilmany is a technology writer based in St. Paul, Minnesota (USA). This article was originally published at asme.org, reprinted here with permission.

Great Views