How well does the vaccine work, what does it mean for bed nets and other malaria-prevention measures, and what is the status of other vaccines in development?

The World Health Organization recommended the widespread use of a malaria vaccine on October 6th, granting formal recognition of the vaccine’s efficacy and safety protecting children. The announcement was an historic milestone in the global effort to create a malaria vaccine that has been underway since the 1960s.

“This is a historic moment. The long-awaited malaria vaccine for children is a breakthrough for science, child health and malaria control,” WHO Director-General Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said in a statement. “Using this vaccine on top of existing tools to prevent malaria could save tens of thousands of young lives each year.”

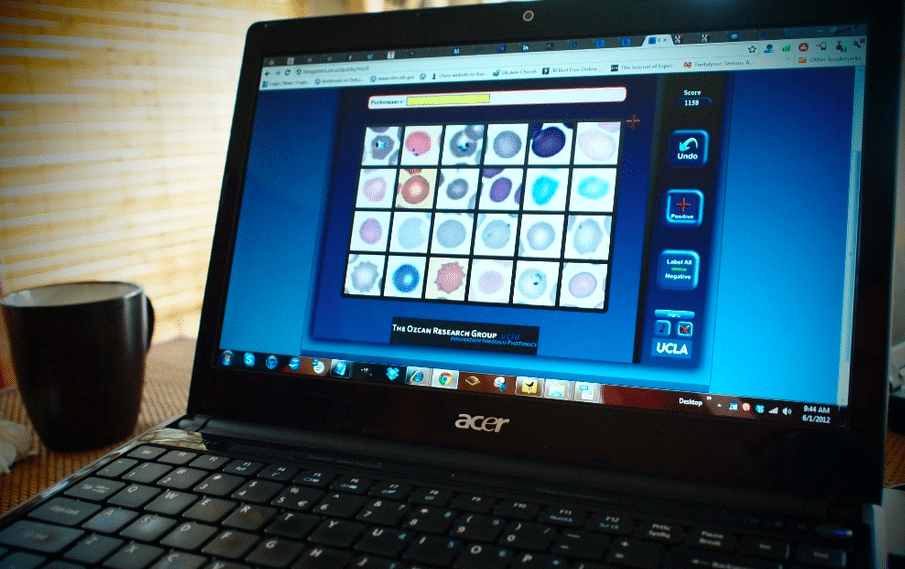

From E4C’s Solutions Library: Three malaria diagnostic tools and case surveillance software

RTS, S: 30 years in the making

The WHO is endorsing RTS,S/AS01, a recombinant protein-based vaccine developed by GlaxoSmithKline under the trade name Mosquirix. GSK has been developing the vaccine since the 1980s, working in collaboration with the US Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, with funding by the PATH Malaria Vaccine Initiative and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

The vaccine protects again Plasmodium falciparum, one of the five malaria parasites in the world, and the most common in Africa. Each year malaria takes the lives of more than 260,000 African children under the age of five. In 2019, roughly 409 000 people died from malaria worldwide, and 94 percent of the deaths were in sub-Saharan Africa.

The vaccine gained regulatory approval in Europe in 2015 for use with infants and toddlers ages 5-17 months. The approval was the world’s first for a malaria vaccine and for any vaccine that targets a human parasitic disease of any kind. Following approval, however, the WHO withheld its recommendation and instead called for more research through large-scale pilot immunizations.

Pilot programs launched in 2019 immunizing hundreds of thousands of children in Malawi, Ghana and Kenya. The pilots will continue until 2023, but after 2.3 million doses administered, early results show that the vaccine is working and it is safe in children.

From E4C’s Solutions Library: Vaccine management software, delivery drones and cold chain technology

How well does the vaccine work?

RTS,S has reduced cases of malaria by about one-third over a four-year period in children ages 5-17 months who receive three doses plus a fourth booster dose. The pilot programs showed that it is possible to administer the vaccine on a large scale and that doing so reaches people who had been left out of other malaria prevention programs. More than two-thirds of children who did not use insecticide-treated bed nets benefited from the vaccine. Even in areas where bed nets are widely used, the vaccine appears to reduce severe malaria by 30 percent.

And it is cost-effective, according to the research.

“This is the most exciting malaria news in years,” Dr. Chandy John, Director of the Ryan White Center for Pediatric Infectious Diseases and Global Health at Indiana University School of Medicine said in a statement issued by the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. “This vaccine could be a game changer when it comes to saving tens of thousands of young lives that are cut short each year by malaria. To have a vaccine available for children that will decrease the risk of severe malaria by 30 percent is a major step forward in the work of malaria elimination and eradication. It will be even more effective in combination with other malaria prevention measures already implemented.”

What does the vaccine mean for other malaria methods of malaria prevention?

It turns out that vaccinating children does not appear to reduce the rate at which people use bed nets. When bed nets and vaccines are deployed together in a community, more than 90 percent of children benefit from at least one method of malaria prevention.

The malaria vaccine also appears to have no negative effect against the rates of childhood vaccination against other illnesses.

Bed nets and other malaria-prevention measures – indoor insecticide spray and anti-malarial drugs – are still recommended as ever, with no changes based on the introduction of the vaccine.

How does RTS,S compare to other malaria vaccines in development?

The WHO’s goal is to have a vaccine that provides at least 75 percent efficacy against malaria by 2030. Other vaccines are in development now, and some appear to be more effective than RTS,S. The most effective vaccine to date may be R21 plus the adjuvant Matrix-M, which had a 77 percent rate of protection in a phase 2 trial in Burkina Faso, as reported in The Lancet on May 15, 2021.

R21 may also be easier and cheaper to manufacture compared to RTS,S, study suggests. The vaccine remains under study before it is eligible for regulatory approval.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tested another vaccine candidate, PfSPZ, in Kenya and considers it promising, as well. A sound prediction may be that a handful of vaccines gain regulatory approval in this decade.