Cuba has had a sophisticated do-it-yourself movement developed by a well-educated populace cut off from access to parts and products. Distribution has been strangled under a US economic embargo, now in its seventh decade, and until recently, the Cuban state imposed strict rules on private business and investment. Undaunted, Cubans responded with engineering acuity to make what they need, and repair, retrofit and transform the things they have.

Now the island nation’s DIY devotees are stepping out of their hobbyist confines into territory usually reserved for the state and large industries. The combination of relaxed rules on the private sector and access to cheap electronics have launched DIY goods into hospitals, farms and even airports.

Cuba’s evolving economy recently legalized cooperatives, entrepreneurship and self-employment, small- and medium-sized businesses and mixed enterprises of public-private partnerships. New economic freedoms were introduced in the early 2000s and the government continued to relax its rules throughout the past 20 years, including the permission to form small business and other kinds of private enterprise in 2021. The changes have introduced improved access to the world’s favorite cheap DIY tools, like additive manufacturing (3D printing), microprocessors and low-cost computers such as Raspberry Pi.

COVID-19 and Cuba’s 3D-printed medical equipment

The availability of 3D printers, such as the one pictured, opened new options to Cuban DIY makers. Photo: Kadir Celep / Unsplash

Cuban doctors developed an effective containment protocol for COVID-19. Compared to the United States, Cuba’s cumulative case rate was one-fourth, and its death rate was one-twelfth that of its northern neighbor, according to research published in December 2021 in the American Journal of Public Health.

The nation’s vaccine response was no less impressive. In less than three years, Cuban scientists developed five vaccines against SARS-CoV-2. Containment and vaccine development were strong, but the nation’s hospitals suffered from shortages of medical products. Protective masks, swabs for PCR tests and other medical equipment were in scarce supply.

Rising to the challenge, a group of DIY hobbyists eased the supply-chain failures with their 3D printers. Among their contributions were visors, ear-savers and other products made through additive manufacturing. Abel Bajuelos, a musician and industrial design enthusiast with a small workshop in Havana, was in charge of coordinating the work, channeling home-printed supplies into the national healthcare system.

In October 2020, the first 500 lung ventilators with 3D-printed components manufactured entirely in the country went to work in medical centers.

The Center for Neurosciences of Cuba (CNEURO in Spanish) had been Mr. Bajuelos’ client since before the pandemic. Using that connection, he was able to direct a network of collaborators to distribute their creations throughout the country. Within two months of the start of quarantine, Mr. Bajuelos’ network had delivered 1780 protective masks to Cuban hospitals. Hosptials also had stockpiles of 3D-printed ear protectors for their N95 masks and parts for medical devices.

At the height of the pandemic, ventilators were in short supply. Part of the problem was political. In 2018, the United States-based medical device manufacturer Vyaire Medical Inc bought two ventilator manufacturers based in Switxerland, Imtmedical AG and Acutronic Medical Systems. The companies had been supplying Cuban hospitals, but suspended sales after the acquisition to comply with the US embargo.

CNEURO turned to Bajuelos and his DIY network for help with the ventilator shortage. Three weeks later they had a working model, based on a home-brewed design developed as a project released by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

The state-owned company Grito de Baire signed a contract for mass production, and in October 2020, the first 500 lung ventilators with 3D-printed components manufactured entirely in the country went to work in medical centers.

Mr. Bajuelos’ workshop is now one of the most recognized centers of additive manufacturing technologies in Cuba. Its services cover the manufacture of functional prototypes, mock-ups, 3D scanning, digitization, reverse engineering and parts optimization.

“I had my first 3D printer thanks to my family living abroad,” Mr. Bajuelos says. “Also, it is a piece of basic equipment. Don’t go thinking that it has an industrial scope.”

Though he downplays the power of the machine, Mr. Bajuelos’ company Addimensional has collaborated with almost twenty private and state-owned businesses. He has also worked with ordinary people who need to solve specific problems and do not have the components or tools to do so.

The state, however, has not supported that success.

“The national industry still resists the use of 3D printing despite our good results, because they see it as little toys. In addition, there is still a certain skepticism regarding the initiatives coming from the non-state sector on the island,” Bajuelos says.

Despite the setbacks, Bajuelos is confident that additive manufacturing will continue to gain relevance in the Cuban landscape. For the maker, his creations constitute a set of far-reaching solutions that can promote greater technological sovereignty in the Caribbean country.

Cheap computers and the DIY Internet of Things

Javier Castellón obtained his diploma in automation engineering in 2018. For his final research project, he developed a monitoring system to make more efficient use of fertilizers and reduce pesticides in a Cuban precision-agriculture program. The system is composed of Web-connected devices that constitute the Internet of Things (IoT).

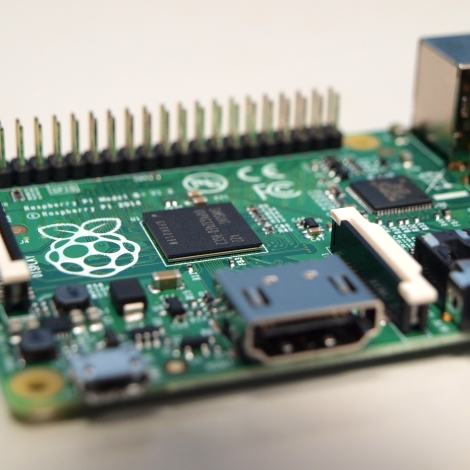

“This system allows the monitoring of environmental parameters measured by a wireless sensor network and phenotypic survey of crops. The architecture consists of a Raspberry PI as IoT gateway that works as a data server and a client application for mobile devices of the Android platform. The server was programmed in Python, using the TCP protocol,” Mr. Castellón says.

Tests demonstrated the feasibility of using free hardware and software in the development of low-cost automated systems.

Mr. Castellón deployed his innovation in a protected crops unit in the Cuban province of Villa Clara. The control tests demonstrated its functionality and the feasibility of using free hardware and software in the development of low-cost automated systems. The demonstration also had the loftier goal of clearing a path toward technological independence in the country, which is especially important in an economy under embargo.

Giselle Santamaría is another pioneer of innovation with cheap computers. the telecom engineer designed and built an intelligent video surveillance system using Raspberry Pi. The system connects a camera, a pair of servo motors and infrared LEDs to the single board computer. The device can look around and record video both day and night in low-light conditions.

“One of the functions of this equipment is to detect intruders and notify them without the use of a cable. It can also operate remotely, manually,” Ms. Santamaría says.

The tip of the iceberg

These projects are just the tip of the iceberg, says Alejandro Pérez Malagón, professor of automation and computing at the Technological University José Antonio Echeverría in Havana, or CUJAE, as it is known by its Spanish initialism.

“All over Cuba, many people are trying to make their lives easier or more beautiful through self-made projects. You don’t have to be an electronic engineer to make it happen,” Dr. Pérez says.

In Cuba, researchers and engineers take on many kinds of self-made projects. One group of scientists is dedicated to building drones for monitoring agriculture. Their surveillance drones have also been used to assist operators at Havana’s national airport. Around the island, amateur mechanics convert their combustion vehicles to electric, stripping out the engine, transmission and exhaust system to replace them with electric motors and batteries. That work, too, is aimed at independence, attempting to ween drivers from dependence on foreign fuel, as well as improve the sustainability of the vehicle.

While Cuba’s makers strive to reduce their need for outside products, their work also connects them to the outside world. The DIY ethos ignores borders. And so does the Internet.

“Worldwide, all kinds of people are taking advantage of the wealth of information available on the Internet to build cool projects on their own.” Dr. Pérez says.

About the Author

Claudia Alemañy Castilla is the 2022 Engineering for Change Editorial Fellow and an award-winning journalist who splits her time between homes in Cuba and Spain. Among her accomplishments, Ms. Alemañy Castilla has developed the COVID-19 Cuba Data Project for Juventud Técnica Magazine in Havana, Cuba, where she was a staff reporter specialized in science, technology and environmental journalism. She has also reported for Women in Science (a publication of País Vasco University), the Cuban Institute of Cultural Research ‘Juan Marinello,’ and others.