The engineering and design firm D-Rev announced the public launch of its extremely low-cost ReMotion prosthetic knee last month. The news culminated a seven-year journey from idea to prototype, field tests, redesigns and finally the product that we see now. A look at that process shows the right way to build a product that changes lives and that people actually use. This is a brief history of a new prosthetic knee that serves amputees in that huge market, 4-billion strong, of people who earn $4 or less per day.

ReMotion began as a student project at Stanford University in 2008. Working with the prosthesis-fitting health organization JaipurFoot (BMVSS) in India, a student team prototyped the JaipurKnee. JaipurFoot was seeking a replacement for the then-current standard of cheap knee prostheses, which were little more than a hinge and a rod.

A better knee could serve a lot of people. More than 9 million people worldwide may be in need of a prosthetic knee and without prospects for treatment, according to a study published in 2010 in the journal Prosthetics and Orthotics International.

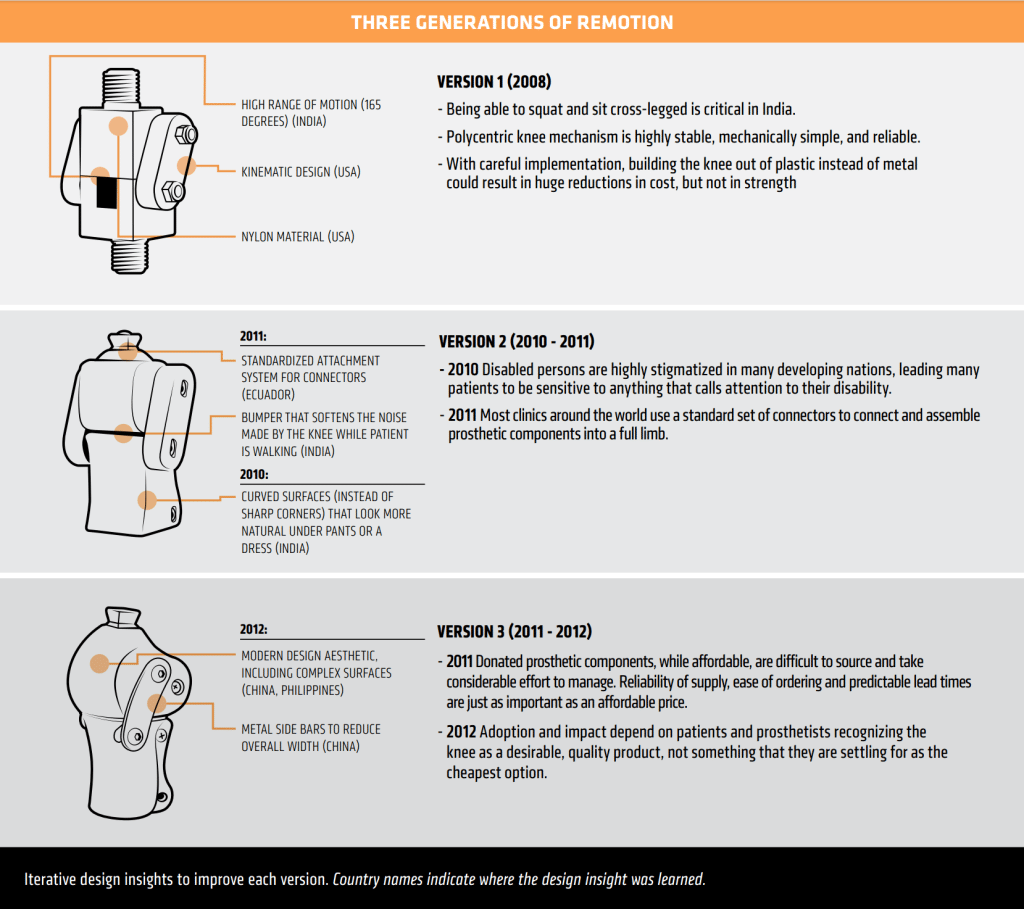

Meeting their needs meant developing a polycentric knee, which, unlike a hinge, moves on more than one axis to perform more like a real knee. The problem is that polycentric designs at the time were targeted at patients in high-income countries and cost US$500 to $10,000. The Stanford team created a prototype that cost only $20 to produce. Its simplicity and materials kept the cost down. Rather than build it entirely out of metal, the knee consisted of five nylon plastic pieces and four fasteners.

The students formed a start-up called ReMotion, then merged with D-Rev in 2011.

Patients want a knee that provides stability and a natural walking motion that functions seamlessly in rugged and wet environments, minimizes noise when the knee swings into full extension, and looks natural when worn under clothing – Sam Hamner

At the outset of early trials and data collection at JaipurFoot, the D-Rev team had anticipated that stability would be at the top of the list of user’s concerns. But surveys instead revealed two different targets for improvement: The noise that the knee makes when it fully extends, and the shape it takes under clothing. It turns out that people were concerned about drawing attention to the fact that they wear a prosthesis. The redesign began to take shape, focused on improving the chance of adoption – the likelihood that amputees and the prosthetists who fit their knees will choose the ReMotion knee.

“For patients, this includes designing a prosthetic knee that provides stability while allowing for a natural walking motion, functions seamlessly in rugged and wet environments, minimizes noise when the knee swings into full extension, and shaping the prosthetic so it looks more like a natural knee when worn under clothing. For prosthetists, this means designing the knee to work with standard prosthetic components and allowing for critical adjustments of alignment and friction,” says Sam Hamner, a former design engineer at D-Rev involved in the knee project.

Compare ReMotion to similar products such as the AT Knee in our Solutions Library.

Testing provided insight into the needs of the knee’s users, but even the act of surveying the users to understand their needs required an understanding of their needs. The ReMotion team learned through experience that people would not fill out their surveys properly if they contained the wrong questions, wording or languages, Krista Donaldson, CEO of D-Rev, and her team wrote in a 2014 article in DEMAND: ASME Global Development Review. When asking about a patient’s mobility, for example, the team had to toss out questions about culturally irrelevant activities such as bowling and golf.

A less bulky, quieter Version 2 took shape in 2010 and 2011. By that time, Version 1, also called the JaipurKnee, had been fitted to 4700 patients at the JaipurFoot Organization.

The third and current version launched in 2013. By that end of that year, more than 5000 patients were wearing a version of the ReMotion knee. D-Rev had partnered with clinics in 13 countries to distribute and test their prototypes.

The newest version has a slimmer, more natural-looking profile. Plastic side bars have been switched for thinner metal struts. It resists buckling when the heel strikes, and it reduces fatigue with a smooth, energy-efficient swing. It has 160 degrees of motion to allow actions such as kneeling, squatting, and riding a bicycle. And, like its forebears, the knee’s mostly plastic construction gives it an edge in heat, dirt and humidity, all of which are common in the countries where it is being used.

But the design is never finished.

“We are currently taking payments and shipping knees around the world. We expect that customer feedback from our first production run will be critical and that our response to that feedback may require changes to the product in the future,” says Nicole Rappin, Operations Manager at D-Rev.

The original JaipurKnee is still serving patients at the JaipurFoot Organizaiton. It was a solid design that has persisted through the years. D-Rev recognized its value and put in the time to improve it. Field testing, partnerships with clinics around the world and a commitment to low-cost, high-quality design have all conspired to create a proven, sought-after prosthesis. That’s what it takes to turn a prototype into a product.

Nicely put, Kudos!