Jed Guinto has puzzled over how to improve a chopping machine that he built to cut water hyacinth and other plant waste into small pieces. When the machine works well, it chops the material into smaller chunks using a machete blade on a roller disk. Guinto then tosses the chunks into a grinder that he also built. When that works well, its cement rollers break down the hyacinth chunks to a size fit for a briquette press. Mixed with sawdust, paper and water, the ground hyacinth is compressed to the size of a hockey puck and dried for use as cooking fuel.

The fuel briquettes save money for cooks in the Philippines where Guinto trains carpenters to build and test the machines. The presses work. The problems are with the choppers and the grinders.

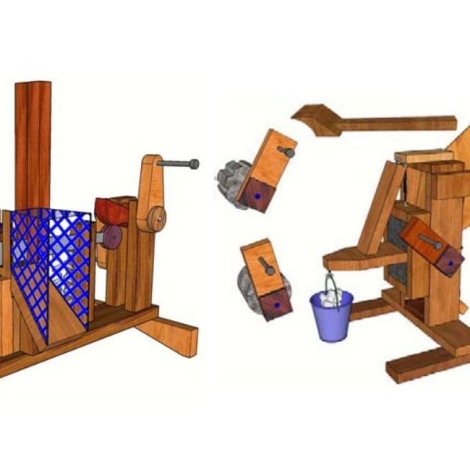

“After two hours of intensive use the steel axle would loosen away from the wooden arms,” Guinto told E4C in an email. “So we decided to weld the axle with another metal rod to complete the durability.” Welding adds another layer of complexity to the build, however. The machine, called the Easy Bio Chop, its sister device the Easy Bio Grind and the fuel briquette presses themselves are designed to be easy to build from widely available parts.

Guinto saw the press in a YouTube video posted by its designer, Lee Hite and a team from Engineers Without Borders – Cincinnati Professionals Chapter. Now he is part of a small, international network of engineers who experiment with improvements on chopping, grinding and pressing machines. They share their results with each other through email video and uploaded documents.

Now the designs teeter-totter between easy to build and effective. Effective devices are hard to build, but easy-to-build devices are not as effective.

Designing an easy-to-build chopper-grinder-thrasher is “critical” to household fuel briquette making, Hite says. “This is a much more difficult endeavor than most people realize,” however, he says.

“Clearly, the grinder and chopper devices I have are a long way from an ideal solution. The fact that Jed decided to build both the grinder and the chopper is a demonstration to me of just how badly the world needs a good design,” Hite says.

Performance sacrifices

Now the designs teeter-totter between easy to build and effective. Effective devices are hard to build, but easy-to-build devices are not as effective.

Hite’s plans are open source and freely available online. While Hite has designed his machines over the years, another engineer and friend of his called Richard Stanley has developed his own solutions. Stanley first opted for effective but difficult to build. His TMC, which stands for Thrasher Masher Chopper, is an all-metal 75kg brute that requires lots of welding and close tolerances. He designed it in 2002 with the Uganda Industrial Research Institute. “It indeed proved… difficult to replicate unless you had access to a well equipped workshop, which is fine for urban settings but impractical for the rural and peri-urban environment,” Stanley says.

The Easy Bio Chop and Bio Grind came next as an answer to the easy-to-build side of the equation. They don’t need welding, but, as Guinto points out, they can break down without a welding modification. “It is important to say that neither device is an ideal solution. They are simply an attempt at solving the problem when nothing else will do. It is also an attempt to spur ideas and development by other people,” Hite says.

The Mini TMC shown here has an optional mount for a bicycle to pedal-power the machine. Image courtesy of Richard Stanley / Legacy Foundation

Stanley co-directs the Legacy Foundation, an Oregon-based technology design and training organization with operations in 45 countries. Working with communities in Guatemala, he has developed a mini TMC that is easier to build.

“The mini TMC or ‘molino a mano,’ is a vast improvement on the earlier TMC and it is finding good acceptance. There is indication that the users might prefer use of leg power to increase output and duration of effort and we are thinking about treadle and/or pedal power adaptations,” Stanley says.

He demonstrates the hand-turned version in this YouTube video.

The world needs a better biomass processor

These designs have promise and they’re improving through the tests and creativity of people like Guinto in the Philippines and communities in Guatemala that work with Stanley. But there might be better ideas out there. Hite has asked for new ideas – new modifications and new designs.

“One of the nice things about E4C is its ability to engage many people interested in development. While Richard enthusiastically contiues his development effort, we both agree that the world desperately needs a low-cost, easy to build and very effective device to reduce biomass for briquette production at the family level,” Hite says.

For questions and to share ideas, please contact Hite through his open-source plans portal and Stanley through the Legacy Foundation’s site. You can also post your comments below and we’ll pass them along.