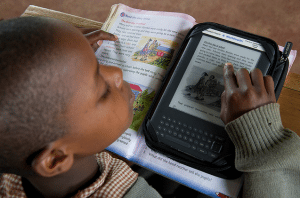

Designers in our field often hammer home the point that the best technology is often the simplest one, but that may not be the case for reading devices. E-readers, namely Kindles, may beat the dead-tree reading devices known as books in schools in developing countries.

The US- and Spain-based Worldreader has shown that Kindles hold several advantages over books. They don’t require libraries, for example. Kindles drastically cut the storage and delivery costs of paper books. They also boost test scores among grade-school students, according to controlled study funded by USAID.

Unlike books, however, Kindles can suffer broken screens and they are at the mercy of the sometimes-unreliable energy access common in developing economies. Here is how Worldreader is overcoming those technological hurdles and escalating its operations to provide e-books to 1 million people by 2015.

Notebook

50%: Students in sub-Saharan Africa with little or no access to textbooks

$0.00: Cost of Kindles to WorldReader’s recipients

3000: Number of Kindles Worldreader has distributed

100: E-books loaded onto each Kindle before distribution

6: Countries where WorldReader works

1 million: Students who may have access to e-readers by 2015

4.8% – 7.6%: Improvement in reading scores for Ghanian students with Kindles

True book lovers

Worldreader is a young organization, founded in 2010 in Barcelona, Spain (with offices now in San Francisco, California, and in Accra, Ghana), by people with an obvious love for books. We know this, in part, because the staff’s biographical blurbs list each person’s favorites.

The program sprang from the idea that Kindles might be more practical than books in sub-Saharan African schools.

[quote author=”David Risher, Worldreader’s co-founder and CEO (favorite childhood book: The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe).”]E-readers can have an even bigger impact in the developing world than in the developed world, because the need is so great and costs are coming down so quickly. I hope that we help this happen, in much the same way that cell phones have leapfrogged landlines across much of the planet, making the world a better place for all.[/quote]

In their first year, Risher and his team had the foresight to put their theory to the test and start gathering data, including reading test scores of children who received Kindles.

They found that elementary school students’ scores increased by 4.8 to 7.6 percent when they had Kindles compared to control groups of students who did not. The scores are according to an assessment designed by the Ghana Basic Education Comprehensive Assessment System, and the full results are recorded in this paper published on Worldreader’s site.

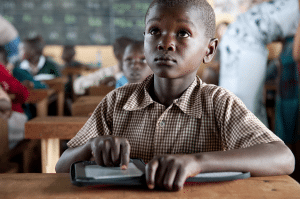

By the end of January, Worldreader has distributed 3000 Kindles to students in six countries: Ghana, Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Tanzania, and South Africa. The devices cost nothing for the students and teachers. Amazon sells them at a discounted rate to Worldreader. Worldreader loads each Kindle with at least 100 books and delivers them with cases and lights.

While most of the books offered are in English, Worldreader is pushing to include other languages and also books written by regional authors. The program provides 105 titles in in Kiswahili, 19 in Kinyarwanda (spoken in Rwanda and parts of Uganda) and five in Twi (an indigenous Ghanian language).

If the students had biographies on Worldreader’s site, African books would rank among their favorites. The most popular titles are not yet tallied, however.

Improving the tech

Broken screens were an unforeseen problem from the outset. The same study that found improved test scores also found that 40.3 percent of the Kindles in a random sample of 600 devices broke. Analysis later revealed that screens were the most vulnerable part. Amazon has since improved the hardiness of its screens in a subsequent generation of Kindle, and Worldreader is experimenting with different styles of protective cases.

We wondered if charging the devices was a problem in places where power can be unreliable. But with the Kindle’s battery-friendly e-ink display, the time between charges is measured in weeks, not hours. So, charging hasn’t been a problem, says Nadja Borovac, Worldreader’s marketing manager (books that have influenced her: Song of Solomon, Of Mice and Men and Beowulf). Even so, the organization is looking at upgrading the Kindle cases by adding solar panels.

Photo by Jon McCormack / The Kilgoris Project / Worldreader

“We’re investing in solar technology now, so that the e-readers can always stay charged. In five years, I expect that will be taken for granted, that e-readers never need to be plugged in,” Risher says.

Worldreader’s next milestone is to distribute 1 million e-books by the end of this 2013. Then the organization plans to hit 1 million again by 2015, but this time that number could be the e-readers distributed, and not just the books that are on them.

Story time

David Risher shares some of the insights and a moving experience that he has had since founding Worldreader.

“On a trip to Ghana, I loved walking down the street and seeing kids in our program proudly carrying their e-readers. And with no worries at all of their being taken from them,” says David Risher, Worldreader’s co-founder and CEO. “One thing people often ask me (and they look at me like I’m a bit crazy when they ask) is: ‘Won’t theft be a problem?’ Frankly, we didn’t know the answer before we started, but so far, we’re finding that (as one of the kids in our program told us early on), ‘Thieves don’t steal education.'” Photo courtesy of Worldreader

E4C: Would you share an experience that has kept you interested in this project?

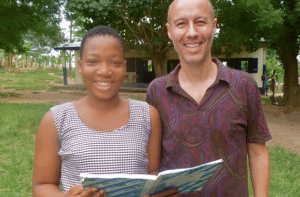

David Risher (right): So many! Reading with Okanta Kate (left). She is a Ghanaian high-school student who has read hundreds of books thanks to our work, and now wants to be ‘the most famous writer in the world.’ I find that incredibly motivating. She’s been so moved by our work that she now wants to leave a mark on the world. The two of us read her poetry together, and I deeply enjoyed hearing her read to me. And she felt the same way hearing me read her words. [Click to see one of her poems, “Agony of a Woman“]

Photo courtesy of Worldreader

How it all began

David Risher explains the origins of Worldreader in this video on YouTube. For more information and to find out how to contribute, please visit Wordlreader’s site.