This methodology can guide ethical decision-making in the practice of sustainable global development.

Syringe design presents a surprisingly complicated problem. Marc Koska introduced this case study in a TED talk in 2009: While working to develop a low-cost syringe for communities in the developing world, you, as a designer, hit a crossroads. Constructing the syringe to auto-disable after a single use is an important safety feature but it significantly increases the cost. The feature makes the syringe potentially unaffordable for some hospitals and clinics for which you’re designing it. If you don’t add the safety feature, however, you enable the potential spread of disease. How do you proceed?

Social entrepreneurs design and implement sustainable and scalable solutions to pressing social challenges across the world. Auto-disabling syringes could be one example.

Reflecting on ethical questions requires that innovators are emotionally engaged and can effectively assess the implications of their actions.

Ethical intricacies abound in social entrepreneurship. Reflecting upon such questions requires that innovators are emotionally engaged and can effectively assess the implications of their actions. That is only accomplished through discussion and honest reflection.

Grassroots diplomacy can navigate the delicate challenges of working in developing communities (or in different cultural contexts) in a harmonious and effective manner. The ability to develop a network of relationships is a hallmark of visionary social entrepreneurs, as is the ability to recruit, lead, and inspire staff, partners, and volunteers.

During their field work, innovators interact with diverse parties including local communities, non-governmental organizations, governmental and UN agencies, religious organizations, political groups, bureaucrats, local industry, US corporations, tourists, etc. In these interactions, innovators will observe and experience tensions. Ego and community tensions and dynamics are inherent in this work.

Even though there is no perfect solution, it is possible to make wise or thoughtless decisions that lead to strong or poor courses of action.

Social entrepreneurs might get asked for grease payments or even be propositioned for a dowry. Conflict is not rare. They might even observe other groups, or their own group, compromise the core concept of self-determination. Innovators must learn how to work in developing communities in a harmonious and effective manner to catalyze social change with their technology-based ventures.

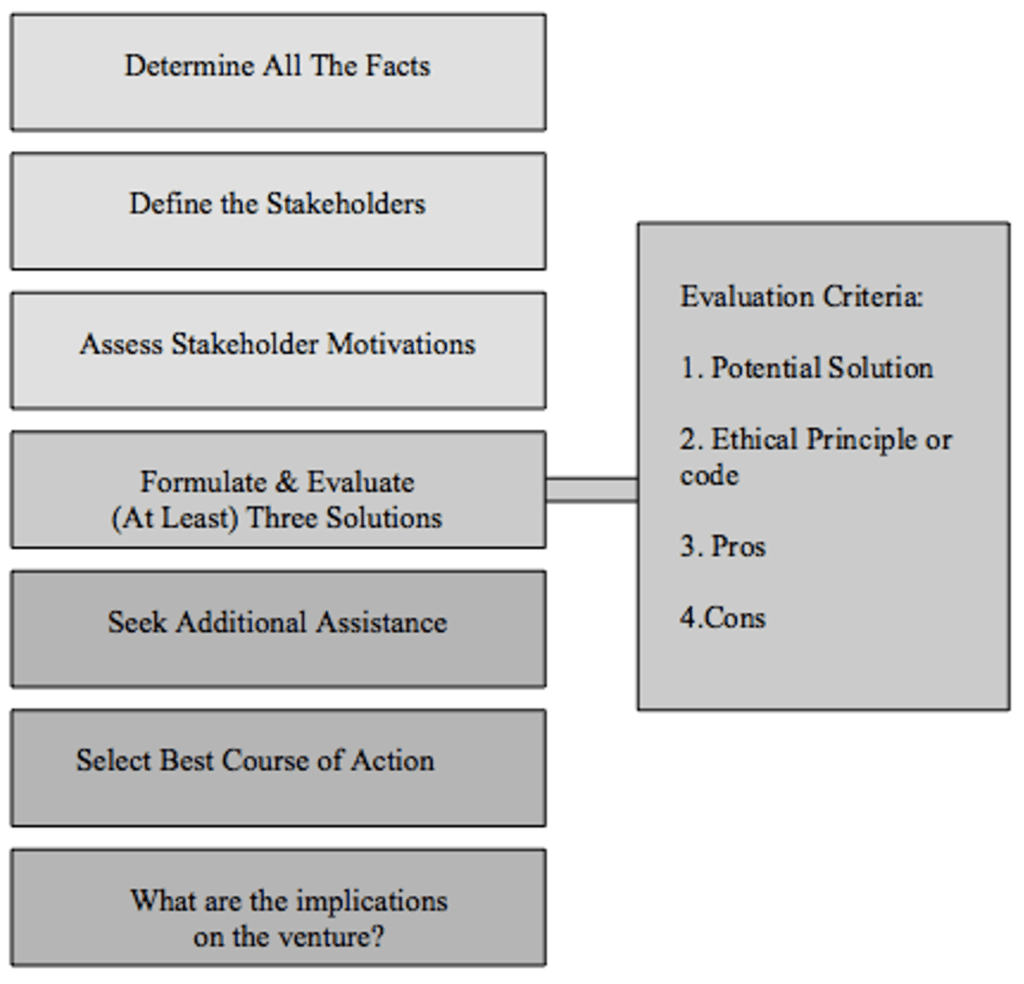

Methodology for Ethical Decision-Making

What does this have to do with syringe design? The syringes pose an opportunity to think through a problem that doesn’t have a perfect answer. In other words, the kind of problem that innovators encounter during their interactions with communities and other stakeholders in their work. Even though there is no perfect solution, it is possible to make wise or thoughtless decisions that lead to strong or poor courses of action.

This chart describes a methodology to make good sound ethical decisions.

Step 1: Determine the facts in the situation – obtain all of the unbiased facts possible. Clearly state the ethical issue.

Step 2: Define the Stakeholders – those with a vested interest in the outcome.

Step 3: Assess the Motivations of the Stakeholders

Step 4: Formulate (at least three) Alternative Solutions – based on information available, using basic ethical core values as a guide.

Approaches [1/2/3: repeat for every action]

- Potential solution

- Ethical Principle or code

- Pros

- Cons

Step 5: Seek additional assistance, as appropriate – engineering codes of ethics, previous cases, peers, reliance on personal experience, inner reflection

Step 6: Select the best course of action – that which satisfies the highest core ethical values. Always explain reasoning and be able to justify your stance viz. other approaches.

Step 7: (If applicable) What are the implications of your solution on the venture? Be able to explain the impact of your proposed solution on the venture’s technology, economic, social and environmental aspects.

Low-Cost Syringes: Some Solutions

After applying that methodology to the syringe problem, some carefully considered solutions might emerge. Students did just that at the Humanitarian Engineering and Social Entrepreneurship program that I used to lead when I was at the Pennsylvania State University. One trend among many of their propositions was that they didn’t accept the problem as a choice between two options. Instead, they introduced the variables that present themselves with context. They included some of the many stakeholders in a solution.

The students didn’t accept the problem as a choice between two options. Instead, they introduced the variables that present themselves with context.

For example, Molly Eckman’s preferred solution:

“Negotiate a deal with the health ministry to buy the syringes with the auto-disable feature in large bulk for less per unit to distribute or sell to hospitals and clinics across the area… If successful, it provides a win-win situation for essentially all stakeholders… The risks, while not insignificant, would not result in more infections due to our product, thereby eliminating the possibility that the manufacturer would be blamed for further infections. Current success that UNICEF has had with making deals and providing funding for nations to use their auto-disable needles indicates that this solution is very possible and would be effective.”

Taylor Lyle proposed a design innovation that would disable the syringe after the second use (not the first). The idea is a compromise that could effectively double the value of each syringe but reduce the risk that it is used on lots of patients.

And Jen Volz proposed to nix the auto-disable feature and sell cheap syringes in tandem with a national mandatory needle cleaning educational program for healthcare professionals.

Depending on the context, motivations, and values of the players involved, the case could be resolved in several ways. Other possible solutions include designing a small red tab to reveal itself after the syringe is used once. Doctors could then decide whether to reuse it. Another solution might be to get rid of syringes altogether and replace them with aerosol (vaccinations for example).

The idea is that we want innovators to do their due diligence. To help, this methodology can show entrepreneurs how to bring personal, contextual, and scientific (technical) factors into consideration in a systematic manner. This due diligence process is just as important as the decision itself.

Ethical decision-making in the praxis of sustainable development will prove to be a fundamental competency of successful social entrepreneurs and innovators who can launch high-impact social ventures and build entrepreneurial ecosystems around them while upholding the fundamental principles of self-determination and equity for all stakeholders.

Further Reading and Case Studies

Mehta, K., Dzombak, R., “Ethical Decision-Making and Grassroots Diplomacy for Social Entrepreneurs: Concepts, Methodologies and Cases,” International Journal of Social Entrepreneurship and Innovation, Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 203 – 224, 2013