The values of a Bolivian school for the indigenous in the 1930s reflect the potential of global development engineering today.

Florencio walks into my office in Oruro, Bolivia every month or so with a new question about water. He asks about water quality, water treatment methods, groundwater recharge, the water cycle, water storage, and so on. Once, after a talk I gave on the urban water cycle, he came in a few days later to ask about the rural water cycle. Most recently, he pulled out a sheaf of papers on reverse osmosis membranes as we sat down. He wanted to know the potential for treating saline water in his small community in the arid Bolivian altiplano.

Florencio challenges my idea of “development” and my own role as an engineer working in Bolivia.

Florencio herds sheep and cultivates potatoes and quinoa for a living. As a farmer and pastor in this place, water presents extreme challenges. His crops suffer from annual water scarcity. With each consecutive year of drought, the groundwater accumulates greater concentrations of salts from the soil, making it unusable as drinking water for his community or his livestock. These are the symptoms of a widespread water crisis in Bolivia1. The situation is the subject of much debate by engineers and bureaucrats, but Florencio isn’t waiting for the government to do something. He was recently elected as an official for his community and is on a mission to find local solutions. His dream is, in his own words, to become “un experto del agua.” A water expert.

At elevations above 12,000 feet, rural life is a battle in the altiplano. The sun is fierce and unforgiving during the day, while the nights drop below freezing. Florencio, though, has adapted to the campo with un-selfconscious determination. He always wears the same outfit to bear the elements: a worn blue vest and scarf, a wide-brimmed canvas hat with a neck flap, and conspicuous black goggles that suction to his forehead. His fingers stick out jaggedly from past breaks, healed in permanent right angles, and I can count the number of teeth he has left. This does not stop him from cracking a wide smile and shaking my hand vigorously four or five times every visit.

He embodies, in a sense, a Bolivian ideal. An ideal that is handed down through community life, born in the centuries-long struggle for indigenous rights in this country, and now channeled into his particular community’s needs. It is, I believe, best described as “ownership.”

Florencio challenges my idea of “development” and my own role as an engineer working in Bolivia. He comes to my office not, as some do, asking for something to be done for him; he comes asking for the knowledge and tools to do it himself.

Florencio has not given in to the subtle psychological battering that international development projects and foreign money tend to inflict on poor communities. That is, he has not victimized himself; he does not see himself as a handout case. Rather, he hungers to see his community thrive by the efforts of his own hands.

He embodies, in a sense, a Bolivian ideal. An ideal that is handed down through community life, born in the centuries-long struggle for indigenous rights in this country, and now channeled into his particular community’s needs. It is, I believe, best described as “ownership.” Ownership over the definition of the good life, and the decisions by which one achieves it.

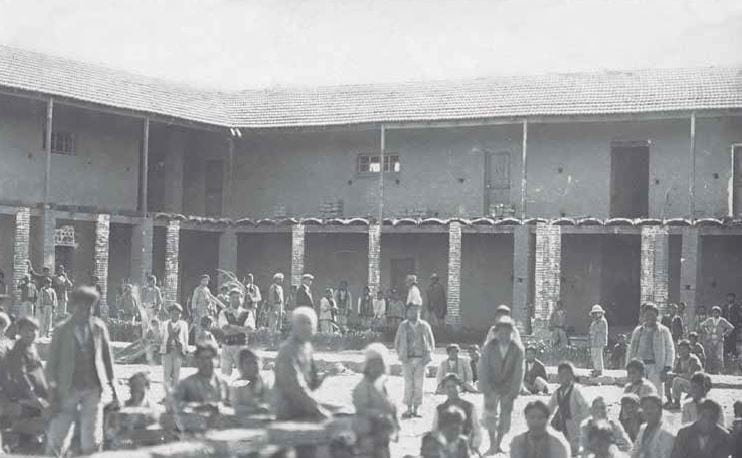

The Warisata community makes bricks and adobe for the school’s construction in 1931. Photo: Carlos Salazar Mostajo

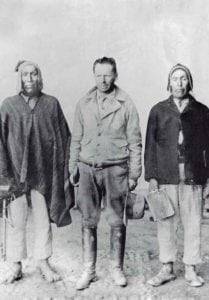

In August 2017, the Bolivian National Art Museum in the capital of La Paz held an exhibit of black-and-white photographs of an indigenous school in the 1930s called Warisata. The school now stands in Bolivian history as a permanent beacon and reminder of that ideal. Elizardo Pérez, a progressive member of the Spanish elite, and Avelino Siñani, an indigenous Aymara leader, founded the school together in 1931. Pérez had been tasked with the “education of the indigenous race of Bolivia.” By the 20th century, indigenous groups in Bolivia had already been subjected to feudal servitude for centuries. “Education” at the time was simply a euphemism for strategic assimilation: Spanish alphabetization, Christianization, and abandonment of rural life.

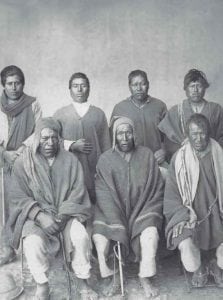

Indigenous leaders helped establish Warisata. Seated, left to right: MallkuII Pedro Rojas, Mallku Mariano Ramos, and Jilakata Mariano Apaza. Standing, left to right: JilakataIII Apolinar Ramos, Fernando Ramos, Manuel Quispe, and Lino Rojas. Photo: Carlos Salazar Mostajo, 1931

In response to this racism and loss of sovereignty among indigenous communities, Pérez and Siñani founded a school based on traditional community structures, culture, and agricultural methods. They taught arts, poetry, and music while at the same time strengthening local agrarian production. They used education to return ownership to the communities themselves, rather than as a mechanism of stripping it from them.

“Education” at the time was a euphemism for assimilation: Spanish alphabetization, Christianization, and abandonment of rural life.

Warisata became a seed of resistance that has grown steadily through social movements in Bolivia over the past 87 years. Many link the 1952 Bolivian revolution and land reform to initiatives that empowered indigenous groups such as Warisata decades earlier. The rise of the indigenous president Evo Morales in 2006 also expresses the same ideals of reclaiming sovereignty over territory, traditional ways of life, education, and the means of economic production.

On a smaller scale, Florencio, too, seems to fulfill the ideas set out in Warisata by claiming ownership over what is his, and, in the face of incredible obstacles, seeking its prosperity.

The photographs in the exhibit were taken by a journalist, Carlos Salazar Mostajo, who visited the school and was so moved by what he saw that he decided to stay and teach alongside the founders. The images show the hard-lined faces of indigenous men and women in traditional ponchos, jaws set, eyes penetrating. Florencio smiles more than the men in the pictures, but when I sit with him I think he could have walked right out of one of the posed 1930s portraits right into the 21st century, showing his neighbors a better example of the meaning of “development” in his personal agency, his eager stewardship even over what is difficult, demanding, and uncertain.

Education is more than simply the transfer of knowledge. It is also a transfer of ownership, to let (and help) men and women define their own hopes and needs.

As 21st-century engineers who care about issues of poverty, injustice, and suffering around the world, we would also do well to seek ways to return this agency to the communities with which we work. This requires more than construction. It urges us to double down on education. As the Warisata school teaches us, though, education is more than simply the transfer of knowledge. It is also a transfer of ownership, to let (and help) men and women define their own hopes and needs. And in doing so, we let them inform us about what we can (and should) offer.

The founders of the Warisata school, Elizardo Pérez and Avelino Siñani, center and right, in 1931. Another community leader, Mariano Ramos, shown left. Photo: Carlos Salazar Mostajo

Florencio provides an example of claiming his agency, teaching me how to do my job better. An acute example of the opposite, however, is found in a small indigenous community just a few hours away from Florencio’s land. The organization I work with partners closely with this community, known as the Uru people. Thought to be one of the most ancient indigenous groups in South America, the Urus have historically been known as a “water people.” Never having owned land or farmed, they built whole communities around lakes and rivers through the Andes, living from fishing and hunting, even living on large rafts for months at a time.

The Urus have been victims of countless “charity engineering” projects.

Today, what was once the second-largest lake in Bolivia, where many Uru communities still maintained their traditional ways of life, has all but dried up. Climate change, drought, and poor watershed management have contributed to an almost complete devastation of the Urus’ cultural and economic livelihood.

The Urus ultimately hope for the lake’s return. Their definition of the good life is in harmony with the lake and practicing their ancient traditions. The lesson from Warisata and Florencio, then, is to co-create ways for these communities preserve their culture, to maintain a connection to who they are as a people even as they diversify economically. This is not only a job for anthropologists, but a sensitive and demanding engineering challenge too. One of the ways the Urus have identified to maintain their lacustrine roots has been by developing fish farms in engineered ponds, requiring a host of technical knowledge and educational opportunities for engineers.

More often than not, however, the Urus have been victims of countless “charity engineering” projects (by leading international NGOs) that erode their personal sense of ownership and culture. For example, the nicest building in one isolated Uru community is a brand-new, freshly-painted computer lab for the children—full of Dell computers, monitors, and keyboards, and nicely embroidered backpacks with the donor’s logo.

…Abandon the traditional ways, learn Microsoft Office, get a job in the city, forget the lake.

Such a project effectively communicates to the Urus and to their children a Western idea of adaptation and development: abandon the traditional ways, learn Microsoft Office, get a job in the city, forget the lake. This is, essentially, the form of education Elizardo Pérez and Avelino Siñani tried so hard to combat almost 100 years ago. An education defined by external pundits—an attrition of agency in the decisions the community wants to make.

Oh, and the new computer lab does not have electricity.

—

Warisata lasted until 1940, a tenure of only nine years, before governmental authorities decided it was a threat to the established social structures and aggressively cut its funding. The authorities even launched a derisive propaganda campaign against it, labeling it “racist.” Its short life, however, created lasting waves of impact. The school serves as a reminder that education that truly seeks a transfer of ownership is more disruptive to the inequitable distributions of power than buildings and water filters and untouched technology will ever be.

Florencio generally carries a backpack full of technical documents and reports he has collected in impromptu meetings with authorities, technicians, and engineers, all focused on water resource management. Some of them, like the technical specifications of RO membranes, are perfectly useless to his rural reality, but we discuss the possibilities all the same.

He is teaching me what is important to him, and I am learning to listen.

1 For more information on the water crisis in Bolivia, see reporting by The Guardian, The New York Times, and National Geographic.

2 Photos and names in captions taken from Photographic Exhibition Catalogue: “Warisata in Pictures – The right to education from the experience of the Ayllu School” accessed at mirador.org.