Stores in Malawi and likely other developing countries carry defective and even fraudulent solar photovoltaic panels. In places where quality standards are not enforced or do not exist, stores and suppliers can sell faulty products to poorly informed consumers. Used solar panels, broken panels, poorly constructed panels and even fake panels with paper made to look like PV cells can have price tags that equal those of new panels in good condition.

Kristine and Michael Sinclair noticed the problem during a trip to Malawi.

“I’m a engineer and my wife is a solar physicist, both with a specialization in solar technology. We spent 3 months in Malawi and were astonished at the poor quality of the modules for sale,” Michael Sinclair told E4C.

“We met with government officials in charge of customs control to see if there were any quality standards in place, any systems in place to help them mitigate this problem of people selling modules that are of a predatory quality. And the answer is there’s nothing,” Mr. Sinclair says.

Fortunately for consumers, solar panels are unusually well suited for visual inspection.

“That works for solar because panels are transparent to light so you have to be able to see in. This wouldn’t apply to a battery or a solar home system because in a panel the guts are on display,” Mr. Sinclair says.

The Sinclairs created a visual inspection guide to help protect consumers.

“Anybody without a formal education could look it over and tell a good module from a bad one. Ideally, if you had no education in this you might want to attend a seminar, and we did that with students. At the end they felt able to use the guide to tell good modules from bad modules,” Mr. Sinclair says.

The International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC), which assesses standards for electrotechnologies, is in the process of publishing this guide as a publicly available specification.

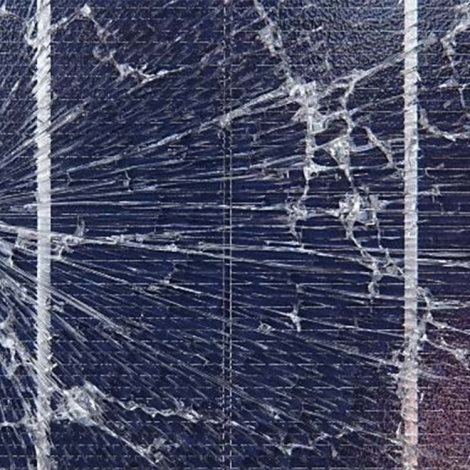

The guide is designed for the visual inspection of front-contact poly-crystalline and monocrystalline silicon solar PV modules, helping the inspector detect major defects. The guide should supplement international testing standards, but not replace them, the Sinclairs write (in the guide). “A lack of visually observable defects is necessary but not sufficient to determine if a module would pass IEC 61215 testing,” the Sinclairs write.

“Many consumers and retailers are not aware of the presence of significant visually observable defects that may limit performance and/or lead to premature product failure… This document was designed with the intention of being a quick tool that is inexpensive to implement, as it does not require any test equipment. Although helpful, no prior knowledge of solar photovoltaics is required to benefit from this guide, and an inspector should be able to be trained in its use in two days or less,” the Sinclairs write.

Please find the complete guide here: Solar PV Product Visual Inspection Guide.

This is an outstanding resource, I intend to share it with colleagues at Engineers Without Borders USA. We have an emphasis on in-country sourcing to support local vendors and create linkages to technicians and access to spare parts. This guide to local equipment inspection and quality assurance is excellent. Also, as an EE in the PV industry who has visited a handful of module production lines in China, these characteristics are many of the same things I was looking for in multi-MW production inspections. Kudos to the authors, really nice work.

Well executed guidance for general audiences. Really good use of visuals – examples of issues and severity scale.