Salitral is a fine place for mosquitoes to breed. Species that spread malaria thrive in its ponds, agricultural canals, year-round temperate weather and periodic monsoon-type rains.

But for 12 days in 1995, eight ponds in Salitral were nearly free of mosquito larva. Their populations were decimated by a high concentration of Bacillus thuringiensis israelensis, or Bti. And the delivery system was coconuts.

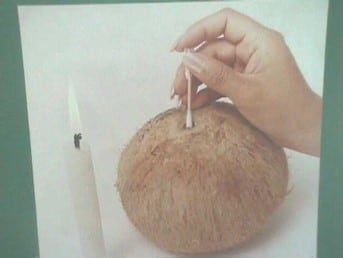

The microbiologist Dr. Palmira Ventosilla developed the homegrown method for incubating Bti at the Experimental Microbiology Lab at the Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia in Lima, Peru. She put together a Bti kit. With it, anyone with basic know-how can inoculate a coconut, wait for the Bti population to grow suitably potent, and then crack the coconut and toss it in a pond.

These biological coconut bombs are apparently harmless to people and most other organisms. The World Health Organization issued a guideline saying that even in drinking water, Bti is not known to be harmful to people. But it is lethal to the mosquito species that spread disease in the world’s tropics.

“We can control 72 species of mosquitoes and blackflies with this method, including Aedes aegypti, a vector of zika, dengue, yellow fever and chikungunya,” Dr. Ventosilla told E4C.

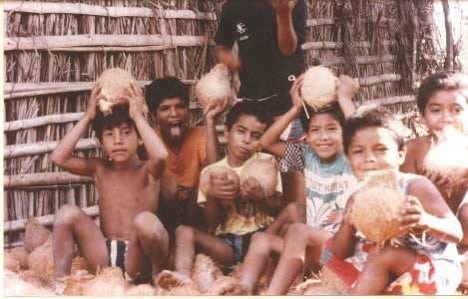

In 1995, grade school students who had made their own Bti bombs threw them into eight ponds. Researchers then measured the rapid decline in concentrations of Anopheles Albimanus larva, one of the mosquito species that spreads malaria.

Bti naturally occurs in soil and on plants and insects. It produces a toxin that kills dozens of species of mosquitoes, blackflies and gnats, but it has little to no effect on other insects, fish, birds or mammals. Including people. That makes it an outlier in the fight against malaria vectors, which is waged most often with chemical pesticides. The bacterium has been commercially produced and sold as a pesticide for decades. It is approved by the US Environmental Protection Agency and has been tested extensively in the United States and other countries.

Bti appears to target only a few species and may have little effect on anything else. To work, mosquito larva must ingest the toxin that the bacterium produces. It is activated by enzymes in the larva’s alkaline midgut, damaging epithelial cells to cripple the insect’s digestive system.

Until Dr. Ventosilla’s coconuts, the problem with Bti was its cost. Now wherever there are coconuts, people have the potential to control mosquitoes. Dr. Ventosilla’s Bti kits contain a cotton swab seeded with 1000 – 10,000 Bti spores, another swab with 40mg of sodium glutamate, a small piece of cotton and instructions for how to inoculate a coconut.

The method may have several advantages over chemical pesticides. Its cost and low toxicity are strong arguments in its favor, but so is the fact that mosquitoes appear to have no resistance. Mosquitoes have been building resistance to chemical pesticides since the 1970s, Dr. Ventosilla writes in a chapter in the book Long-Term Solutions for a Short-Term World. In Peru, 51 species of Anopheles have shown signs of resistance to DDT, organochlorates, organophaosphates and carbamate compounds.

The Salitral experiment was one phase in a decade-long intervention and research project. Dr. Ventosilla and her team distributed Bti kits to 98 families with grade-school students.

Photo courtesy of Palmira Ventosilla

The intervention began with education. Working with local organizations, the researchers helped lead community awareness campaigns, training sessions with families and school lessons in malaria transmission and control. Then the families tested their coconut bacteria bombs. The battlefield was 197.3m2 of ponds throughout the community. For comparison, they did nothing to another set of ponds in the community that covered a combined total of of 298.3m2.

Each coconut contained an average of 2.2 x 105 spores per mL. Experimenting with concentrations, the researchers and the students they were working with in the community seeded four ponds with two coconuts each, and four other ponds with four coconuts. After 96 hours, nearly 90 percent of the Anopheles Albimanus larva had died off in the ponds seeded with four coconuts, and 80.71 percent of the larva had died in the ponds that took two coconuts.

The larva remained absent for about 12 days as the BTI concentrations in the water diminished daily.

In a follow-up study a decade later, Dr. Ventosilla and her team found that residents of Salitral still remembered elements of the education campaign. In surveys, residents of Salitral tended to understand more about malaria transmission, how to incubate Bti and how to treat or drain standing pools of water around their homes to reduce mosquitoes breeding grounds compared to another community that was a control not included in the Bti research. Salitral residents had no reported cases of dengue in that decade and fewer reported cases of malaria than the control town, the researchers found.

The project may have been a vehicle of change for the community, moving it from a passive to an active attitude, the researchers wrote in Mosaico Científico in 2005.

Simple solution but with great effect. The usage of the commonly available coconut to prevent mosquito diseases is an outstanding idea. can also be useful to flooded area during typhoon.