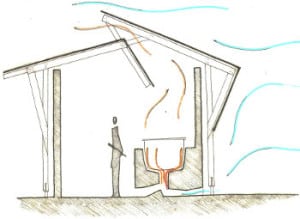

The kitchen’s roof uses the prevailing wind flow to enhance ventilation, and new, hand-built stoves produce less smoke and consume less fuel to improve indoor air quality. Image credit: Charles Newman

By Charles Newman, LEED AP

Guest to E4C

(Scroll down to see the photo essay below)

USALAMA, KENYA – The kitchen was a big problem. My team from the Engineers Without Borders New York Professional chapter and I recognized its deficiencies while we were building four new classrooms for the primary school in Usalama, Kenya. Throughout the three months of classroom construction, we organized daily work schedules, hired subcontractors, and procured materials. Still though, the kitchen loomed as an issue that desperately needed a solution.

The conditions in the kitchen were deplorable and dangerous. Every day, when the cook, Matua Nzoka and three student volunteers made lunch for the school’s 350 students, the kitchen became a literal smoke box. The only ventilation was through a pulled-back roof panel, leaving the walls black with soot. This cave-like box contained several three-stone cooking fires, and nothing much else. There was no interior floor slab, so Matua and the students had to cut vegetables on the ground before putting them on the fire.

With open cooking fires in a poorly ventilated room, the original kitchen was a smoke box. Photo credit: Charles Newman

Matua told me how much he loved to cook for the kids, but “cooking in the kitchen is difficult,” he said. “It is hot, smoky, and it makes my eyes hurt.” The three school girls who tended the fires skipped class for two hours every day to work in the smoky kitchen. They were always happy and up beat – but their dry eyes and coughing told a different story.

I knew that we would be able to solve “the kitchen problem” with only a few adjustments. Previous volunteers estimated a new kitchen to cost around $4000 (USD). I was confident though that by using the entire deconstructed structure (rather than starting from scratch), all the leftover materials from the classroom construction, and a surplus of $1000 in the classroom construction budget, we would be able to complete the kitchen for “free”.

After talking to the school administrators and other members of the community, I got to work designing the new structure. The existing kitchen was a small 10ft. by 12ft. brick building. We accounted for the prevailing wind direction in the roof design, guiding wind both to the fresh-air intakes for the fires, as well as over the top of the structure to ventilate the space inside.

Then we built three stoves, two residential-sized and one industrial-sized, based on the basic clean-burning rocket stove design. The large stove can handle meals for up to 500 students. We handmade the bricks for the stoves from mixtures of mud, sawdust, grass, and ash. The design directs the flames straight to the pots.

In addition to the kitchen, we realized that we should also build a space for safe food storage. This new space would have to be about 300 square feet, with enough room to store a six-months supply of food. To cut costs, we opted to use leftover stone from the classrooms, and sections of old water pipe to create a cool, ventilated space.

A welder in the nearby town of Kibwezi fabricates the pot stand for the stove to serve 500 students in Usalama.. Photo credit: Charles Newman

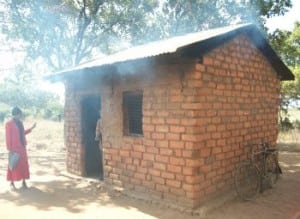

The kitchen, one year later

Last month, I visited the community and checked in on my friends at the school. The new stove saves time and fuel, Matua told me. “We use less wood and the water boils faster,” he said. “It’s so much nicer to cook in here now!”

It was also clear that he no longer had need for volunteers because the stoves burned so efficiently without much maintenance. He and the girls used to start the cooking fires at 9:30am for lunch at 12:30pm, but now Matua starts the fires 11am on his own.

Most importantly, during the construction of the stoves, the masons and I had many discussions about different ways to build them, and I noticed some of them taking notes on the dimensions and materials used in their construction. I learned last month that the same workers built similar stoves for themselves. Two of them have also built five stoves for their neighbors and one for a hotel. And neighboring schools have visited Usalama to learn about the larger stove’s design.

The project caught the attention of Kenyan officials. A few months after the structure was completed, representatives of the Kenyan Education Ministry and Health Ministry stopped by the kitchen and storage area and gave their approval.

Mwikali’s Gift, a non-profit dedicated to development works in Usalama, generously funded the entire construction of the classrooms and the kitchen renovation.

Local masons helped build the clean-burning stoves from handmade bricks. The isolative bricks form a wall around the pot to trap heat from the fire below. Photo credit: Charles Newman

Lessons Learned

When working on the ground on such a large construction project, it is important to remain flexible and resourceful throughout the process. Nothing should go to waste.

It is also important to listen and to incorporate the knowledge and building practices of the community where you are working.I could not have completed this project without the hard work of the community, and their detailed knowledge of local materials. This created a reciprocal transfer of knowledge throughout the project that placed the ownership of the project in the hands of the Usalama community.

I learned more in working on this small kitchen project than on any other project before it, and look forward to bringing this knowledge to more communities throughout Africa and Haiti.

Building the Usalama Primary School’s kitchen, a photo essay

Matua Nzoka, the cook, talks about working in the Usalama Primary School’s smoky kitchen before the reconstruction. Photo credit: Charles Newman

Local laborers separate bricks from the kiln after teaching EWB-USA members the science of brick firing. Bricks contained varying mixtures of clay, saw dust, dried grass and volcanic pumas. Photo credit: Charles Newman

With help from volunteers in the Usalama community, the builders excavated the site for the storage area in one day. Photo credit: Charles Newman

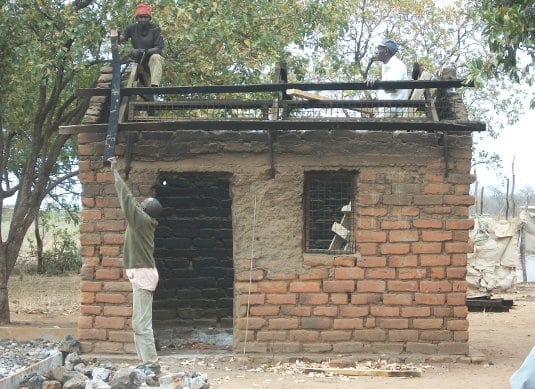

To deconstruct the original kitchen, the workers removed the roof panels, trusses (including every nail) and brick gables. They set all of the materials aside for reuse in the new design. Photo credit: Charles Newman

Leftover wire mesh and purchased chicken wire reinforced the existing mud-brick walls. Photo credit: Charles Newman

In the place of windows, pieces of repurposed plastic pipe are lodged in the walls of the storage area for better air flow. Photo credit: Charles Newman

The main cooking stove is under construction here. It’s based on a rocket stove design. Photo credit: Charles Newman

These are the finished stoves. The community reports that the stoves use much less wood and produce less smoke than the open firest they used before. Photo credit: Charles Newman

The builders resuse roof panels from the old kitchen to make part of the new roof. Photo credit: Charles Newman

The redesigned roof, shown here, harnesses the wind for better ventilation. Photo credit: Charles Newman

Charles Newman is an emerging architect and freelance design and construction consultant for projects in Africa and Haiti. Find out more about his work at www.charlesnewmandesigner.com. You can reach him at charlesnewmandesigner (at) gmail (dot) com or on Skype at “charles.mwendo.newman.”