This article reveals the often-overlooked consequences of excluding women’s voices from the development of technology. The result is harming women now and in future generations. Global development practitioners, including technology designers, should note: While the problem is universal, it is affecting women in low- and middle-income countries in particular.

Data Profiling — How It Works and Why It’s A Problem

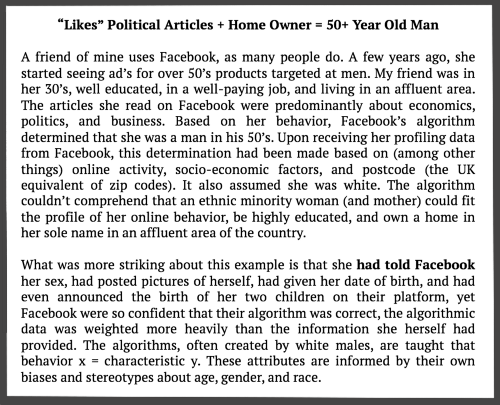

Do you know why or how certain movies are suggested to you on Netflix over others, or how your news feed articles are prioritized on Facebook, or why certain Google search results come to the top over others? Movies, articles, and search results are targeted to you based on your “likes”, your friends’ “likes”, your search history, your political views, information you provide to other apps and devices that you use, and many other personal traits.

You probably already knew that, but have you considered that they’re also based on whether or not you’re a woman, whether or not you’re a parent, and whether or not you’re in the paid workforce? The Adtech industry uses your online behavior to build a profile of you — who they think you are. They may look at your behavior and profile you as a male, between 40–50, heterosexual, married, multiple children, and living in an affluent area. Advertising is then targeted to you based on what a typical man of this age and demographic is interested in, which is heavily based on societal norms, the personal biases of the individual(s) creating the algorithms behind this, as well as stereotypes. This type of profiling happens all the time — just think of how many online or digital interactions you have with various apps and websites all day long. These companies are receiving a steady stream of information about you that they use to refine and add to their profiling of you as an individual. Not all of this data will be interpreted correctly.

Now think about LinkedIn, online recruiters, job search sites, banks, financial lenders, healthcare providers, and governments — this is not about whether you see the latest handbag or cat video anymore, it’s about whether or not your profile comes up in the recruiters search for a new candidate, whether a lender finds you credit worthy, or whether you qualify for healthcare. This is where technology has the potential to exponentially exacerbate bias with unchecked AI, but it could also reduce human bias by putting up a virtual curtain to look beyond one’s gender, race, or other profiling traits. The former is the status quo; the latter will only happen if we act.

This is why we need a focus on gender data+tech.

What is Gender Data+Tech?

When you hear “gender data+tech” what comes to mind? If you’re working in international development, you probably think of the gender digital divide or you might think of the more recent focus on tech-facilitated GBV. Technologists’ minds on the other hand could gravitate to digital rights or possibly the “pipeline problem”. If you’re the type to discover the next best market, then the untapped potential in women’s healthcare and Femtech might come to mind. To all the data gurus out there, you’re probably thinking of data rights, data security, and privacy. A few of you will be thinking about gender data, its gaps and access problems. Then, if you are one of those very few people who straddle some combination of data science, gender studies, policy, and practice you will likely think of AI ethics, and all of the different types of data bias that can occur in machine learning.

In order to define gender data+tech, we first examine the consequences of status quo. In this article, we discuss direct harms and indirect harms associated with data, or lack thereof, and technology solutions. We not only outline the direct harms of getting online today, but also focus on revealing the often-overlooked consequences of women’s’ voices not being incorporated into tech, resulting in indirect harm that will affect generations upon generations.

Three Billion Marginalized Voices — Creating Space for Women and Girls[1]

In order to address the needs of women and girls, we need to ensure that we are consciously putting them first. This might sound obvious to some, but it will be a dividing factor for others.

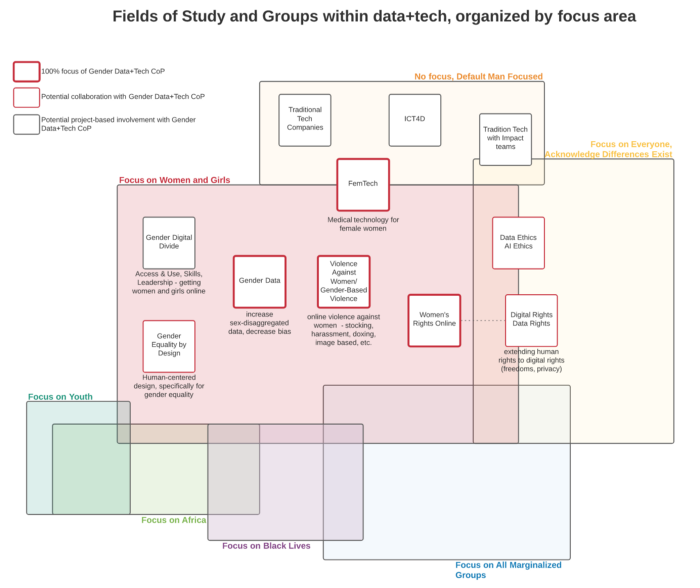

Most of the work in this space does not actually have a primary focus on women and girls. Some work acknowledges that there are differences in our global population and focuses on human rights (data ethics/ AI ethics, digital rights/ data rights), some focus on challenging the power and purpose of technology (Data&Society), while others have a focus on all marginalized groups (Design Justice Network, Data + Feminism Lab, Algorithmic Justice League, We All Count). These are all separately and together necessary spaces for the betterment of society.

This is a visual mapping fields of study and a few predominate groups that are close to Gender Data+Tech, organized by prime focus area. This is populated based on publicly available information and is by no means comprehensive or static. This visual is to provide clarity on gaps as well as identify room for collaboration within the space.

Having a space focusing on women and girls is also separately and together necessary. Without this, conversations (subconsciously) orbit around men as the default, even when led by women. Historically, men/boys raise their hands first, which is a problem when the question relates to the needs of women/girls. Of course, there is room to work together, but this requires a women/ girls focused space that enables the different perspectives to emerge.

United We Stand, Divided We Fall

It’s going to take a cross-cutting gender lens with a truly diverse global perspective to address and create for the futures of women and girls within data and tech. Current coordination and funding efforts lack acknowledgement that this problem cuts across all gender work[2] as well as across all developed and developing countries, Northern and Southern Hemispheres.

No matter what perspective you’re coming from, we can all agree that when looking at issues of gender or women, and technology or data it’s a very minimally explored area that needs to be further developed with frameworks and structures that collectively guide us. The intention of this article is to increase awareness of this issue and galvanize people into action. We need a larger discussion that collectively defines all of the risks for individual women and girls as well as the risk on our economic and social systems that shape gender equality now and into the future.

Direct Harm/ GBV/ VAW

Direct harm against women and girls encompasses intentional violence such as: online harassment, hate speech, stalking, threats, impersonation, hacking, image-based abuse[3], doxing, human trafficking, disinformation and defamation, swatting, astroturfing, IoT-related harassment, and virtual reality harassment and abuse. These types of violence can be easily classified as GBV/ VAW, tech-facilitated GBV/VAW, or online GBV/ VAW because the intent behind the acts is clear, to harm an individual or group. There is a small, but growing body of work on these topics.

Groups that have been focused on this type of tech-facilitated direct harm for some time are the APC and journalists, although the work was historically not intended to focus on women, the targeting of women is common, thus a coalition of women journalists was recently formed against online violence. The child protection communities have also had a strong presence, as it relates specifically to children. Traditional GBV communities are also beginning to take up such topics since tech-facilitated GBV is caused by the same generational problem of power imbalance between men and women.

Indirect Harm/ GBV/ VAW

The way in which a majority of technology, especially digital tech, is being created today is amplifying gender inequalities and discriminating against women and girls. Despite preventing women from accessing jobs, funds, public services, and information, indirect harms against women from the misuse of data and tech is almost entirely overlooked.

Here we are talking about algorithmic bias (i.e. coded bias in artificial intelligence and machine learning), data bias (i.e. missing or mislabeled datasets), data security (i.e. sharing identifiable information), and other gender-blind tech that isn’t incorporating the voices of women and girls (e.g. bots, car crash dummies, and human resources software perpetuating harmful gender norms).

Why Are There So Few Women in Tech Today?

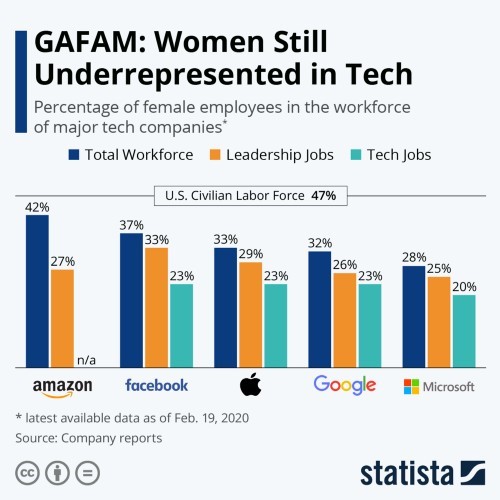

The tech industry, like almost every industry or sector, is full of harmful gender norms, bias, and sexism, but something unique to the tech industry is the extremely small representation of women in combination with the massive amount of growing power and influence tech has on our daily lives.

As Emily Chang so clearly spells out in her book Brotopia Breaking up the Boys’ Club of Silicon Valley an important thing to understand about these problems is that women have been excluded from the technology industry for over 50 years despite being the early developers. To all of those who say that it’s a “pipeline problem” she asks, who created the pipeline? The pipeline problem was created by the tech industry itself, from intentionally hiring anti-social men with the Cannon-Perry aptitude test in the 1960s, to Hundred Dollar Joe at Trilogy rewarding impulsive risk takers from strip clubs in Vegas in the early 1990s, to the original founders of PayPal being outwardly anti-feminist and anti-diversity, selectively hiring men like them beginning in the late 90s. The lack of women in the tech industry today is not because there’s a lack of interest or intellect. It’s because the tech industry pushed out women in the 60s and has been a massive boys club with exclusionary behavior from the 1990s through 2010s, only solidifying such behavior today with the largest tech investors coming from the same proud PayPal Mafia.

Now Let’s Move Forward, Together.

When examining why this problem exists it’s easy to get lost in discussions with people who don’t care about the problem, people who don’t see the problem, or people who lack the will to do something. Instead of focusing our finite energy on this, let’s first start with the low hanging fruit. Let’s coordinate the people who care, see, and have the will to do something about the problem, but don’t know how to do it alone or just need their voice amplified.

We are building Gender Data+Tech Community of Practice to bring together thought leaders to create partnerships, collaborative guidance, and develop solutions. Our goal is to build an evidence base with proven data and tech solutions that focuses on tackling gender inequalities for women and girls.

We, as a small but growing global community, are eager to have the critical conversations about how to ensure diverse voices and perspectives of women and girls are reflected and incorporated into technology today (e.g. demystifying black boxes, documenting training data, use AI to fight against GBV) as well as co-create better technology for tomorrow (e.g. participatory tech, inclusion prediction models, NLP tools for gender professionals).

Please reach out if you are passionate about moving the needle for women and girls with data and tech. We are stronger together and now is the time to shape our future.

[1] The terms “woman” and “girl” are social constructs of gender, thus this includes anyone who self-identifies as a woman or girl. This is also meant to include all female persons, indifferent of their gender identity. Language has been intentionally abbreviated not to dilute or distract from the 3 billion majority who are cis women and girls.

[2] Let’s address putting terminology differences aside for the time being. Gender Equality, Gender-Based Violence (GBV), Violence Against Women (VAW), and Violence Against Women and Girls (VAWG) work often overlaps, some would even argue that they are all the same.

[3] Image-based abuse includes: sharing images or videos without consent, taking images or videos without consent, shallow fakes, deepfakes, cyber flashing, sextortion, sextortion scam, child based image abuse.

About the Author

Stephanie Mikkelson is a development practitioner and global researcher focused on responsible gender data and digital solutions for large INGOs and UN agencies.

A version of this article was first published on Medium. See the original article and others by Stephanie Mikkelson on Medium.