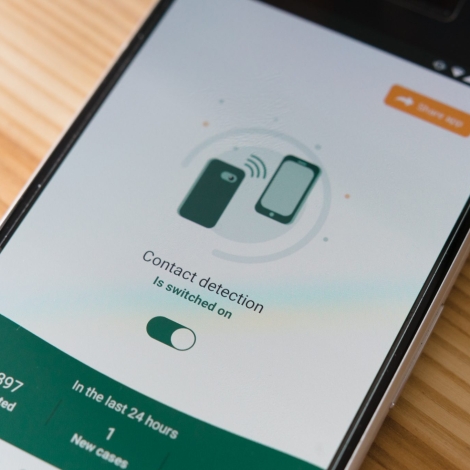

An emerging complementary measure to fight the coronavirus and flatten the new infection curve is the implementation of contact tracing technology. Mobile apps may be a powerful tool for the work to identify, assess, and manage people who have been exposed to a disease.

How it works

So far, we have two types of approaches to the development of contact tracing apps. Let’s explain both with an example:

When person A and person B come to close contact, their phones exchange a personal token using Bluetooth, so they can have a list in their phones of the persons they have been in close contact with.

If the app is using a decentralized approach, when person A tests positive, a QR code authorizes the app to upload the list of persons (list of tokens) that they have encountered. Always without retaining location data. Then person B’s phone can download the list of codes from a person who has had a positive test and compare it with person B’s encounter history.

Without clear user protocols and transparency of the app’s data usage, it can be quite hard for people to adopt these solutions.

On the other hand, if the app is using a centralized approach, it will upload the list of tokens as well as proximity and other interaction data. Some health authorities might choose to upload location data as well. Then an algorithm analyzes the interaction data to determine who should be contacted and sends out alerts.

As with most apps, user engagement and efficacy is critical. However, without clear user protocols and transparency of the data usage of the app, it can be quite hard for people to adopt these solutions.

The lack of protocols or guidelines on how to share sensitive user information contributed to many users and governments being skeptical of the use of contact tracing apps. Apple and Google teamed up to develop a set of underlying protocols for both Android and iOS. Specifically, Apple and Google have developed an application programming interface (API), which in essence acts as an intermediary between different applications. In this particular case, the API allows health applications to send information across Android and iOS and get access to the features they need, such as Bluetooth signals. That way, the developers only need to develop the frontend interface for the users and connect it to this API. Of course, it is not mandatory to develop a contact tracing app under these protocols; there are some agencies that are working on completely bespoke systems of their own.

In regards to privacy, Apple and Google have been transparent. There are some important aspects of how the API handles the privacy of the users. One is that the API will share the strength of the Bluetooth signal so health authorities can set their thresholds for what constitutes a “contact event.” It won’t share the precise length of time two people were in contact, though. Rather, it will only share estimates of exposure time, from a minimum of five minutes to a maximum of 30 minutes, in five-minute increments. Health authorities can use this information to alter their guidance to users based on how long ago the event was. The Bluetooth metadata will be encrypted using the AES encryption algorithm (the same that the US government uses to protect classified information) to protect against it being used to track individuals in reverse identification attacks.

If a user downloads an application and it’s not clear what to do after opening, they will most likely uninstall it.

However, the trust that people have in the privacy of these applications is still a concern. That seems reflected in the numbers of downloads. For example, France launched a mobile track-and-trace app on June 2nd, and by the first two weeks 1.5 million people had downloaded it, representing only 2 percent of the French population. Back in March, Singapore launched a tracing app based on Bluetooth technology, but only 20 percent of the population downloaded it because the citizens weren’t comfortable with a phone-based tracing app. In response, the government started planning on the release of a wearable tracking device that will not rely on smartphone ownership.

In Latin America, many countries have launched apps to auto-diagnose COVID-19 symptoms. None include functioning contact tracing, however. Developers in some countries such as Colombia are still working on contact tracing apps, but on a local level rather than a national level. Instead of implementing the application in the whole country, they implement the application in a city, for example. To ensure the use of the application, the government is planning to make it mandatory to be able to go outside. That, of course, has been controversial.

Instead of launching at a mass level, it might be better to test the application first with small communities and analyze users’ behavior.

In my opinion as a software developer, most of the governments and agencies that are developing these applications are focusing only on the functionality and the optimization of the software, but they are forgetting about the user experience. It matters how an app keeps users engaged, and also how to guarantee secure management of the data collected.

One good example of user engagement is coronavirus.app, although is not a contact tracing app, is related. This app was released in March of 2020, and by July they reached more than 10 millions users. This is because of its simplicity and good design practices. Users can access via desktop and mobile and when they enter the application they already know what they have to do and what they want to see. This aspect is something that is missing on the contact tracing apps. If a user downloads an application and it’s not clear what to do after opening, they will most likely uninstall it.

Another aspect to highlight is to have a focused launch strategy. Instead of launching them at a mass level, it might be better to test the application first with small communities and analyze users’ behavior to know what things need improvement.

In short, contact tracing apps seems to be a good complementary measure to continue reducing the infection curve, but to be effective, a large part of the population must download and use it. The task now is to find a way to instill trust and easily download these tools.

About the Author

Gustavo is an E4C Research Fellow living in Buenos Aires, Argentina and is pursuing a dual M.S. in Systems Engineering and Electronic Arts. He is currently working as a Software Developer at Wingu, an NGO that aims to reduce the technological gap in the social sector. He has two years of experience working with governments and NGOs in Latin America in projects related to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals.