The Palni Hills are 770 square miles (2000 square kilometers) of forest and farmland in Tamil Nadu, southern India, where trees and bees are good for business. The region, in the eastern tip of the Western Ghats ranges, is known for coffee grown under a forest canopy, and, increasingly, for its honey.

In the last 20 years, workers employed at the Palni Hills Conservation Council, a local non-profit, have planted 9.5 million trees, from among 140 native species, on farm and forest lands. The PHCC has also trained men and women, coffee farmers and others in apiculture. The trainers share their know-how, and some proprietary hardware, to supplement people’s incomes with honey and beeswax sales. This is how new digital monitoring tools are improving the prehistoric pursuit of bee farming, and funding reforestation in an ecologically dynamic region (scroll down for a photo essay below).

Central heating and cooling

Like its larger European cousin, Apis cerana indica, the Indian honeybee, needs to maintain a narrow range of temperatures within its hive. Regardless of the weather, the brood must live within 91.5 to 96 degrees F (33 to 35.5 degrees C). When hot days in the Palni Hills forests threaten to overheat the hive, bands of worker bees may fan it with their wings to dissipate the heat. If that fails, a human intervention may be in order. An apiculturist can drape the hive in a wet jute sack.

The bees can also raise the temperature by flexing their flight muscles, a trick that can save colonies from attack by giant Asian hornets. When the hornet enters the hive, dozens or hundreds of bees coalesce around it, forming a ball of muscle-flexing bees that raises the temperature to up to 122 degrees F (50 degrees clesius). The bees can survive the heat, but the wasp dies. Kannan has seen the ball defense in action, he says.

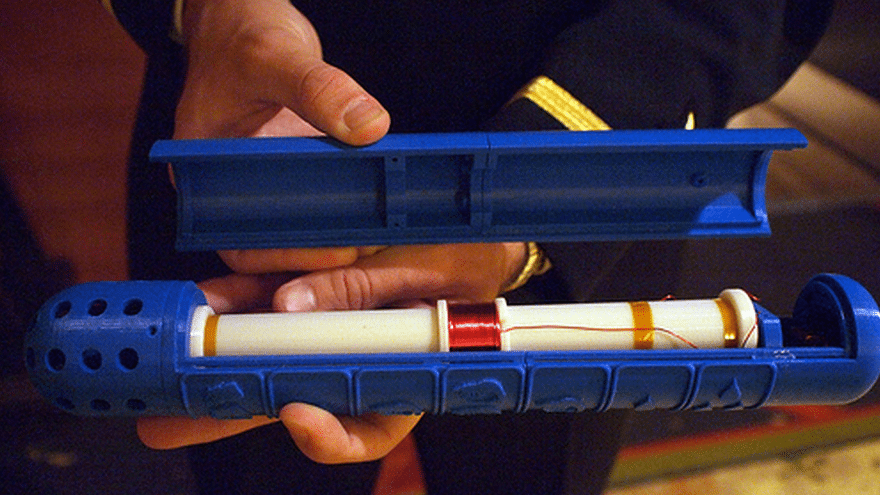

Bee farms use PHCC’s dataloggers to monitor temperature and humidity changes in the hive. The environmental group assembles imported parts into its device, and ties it together with its own software. The design team tries to adapt the device to the conditions in Palni Hills, with new improvements underway.

“Right now we are planning to upgrade the datalogger with one more parameter, a wind-speed monitor,” Kannan Raveendran, PHCC’s president and an Ashoka Fellow, told E4C. “As wind speed is a critical parameter for crops as well as bees, the addition of this to the measurements will make a difference in these days of changing climate.”

The bees hunker down on windy days and don’t collect as much pollen or nectar. Winds make it harder for them to fly with their harvest. The moist pollen that the bees collect in bristles on their legs not only fertilizes plants, it’s also the main ingredient in the royal jelly that the bees feed to their young. In a stiff breeze, it can dry and blow away.

“Crops suffer and bees suffer,” Raveendran says.

When the dataloggers record long bouts of windy days at the hives, apiculturists can feed sugar water to their overworked bees to help them survive.

Hives of clay and bamboo

On average, apiculturists in Palni Hills may have two to five hives. The bees produce about six honey harvests per year, for a total of 33 pounds (15 kilograms) of honey from each colony. At 136 rupees ($3) per pound (300 rupees per kg), the average bee farmer earns 9000 to 22,500 rupees ($200 to $500) from yearly honey sales.

Langstroth hives, with their removable frames on which bees build their honeycomb, dominate bee farms in the west. PHCC, however, employs the simpler top-bar design. Their hives can be boxy or basket-shaped, made of bamboo, cow dung and clay. Bees attach and hang their honeycomb from the hive’s eponymous wooden top-bars.

Reforestation for water

PHCC sells hives and dataloggers, and trees from its nurseries, to support its apiculture training and reforestation programs. After more than 20 years of planting seedlings in Palni Hills, PHCC has played a key role in the health of the region’s forest and the canopy over coffee farms.

At Palni Hills, the Ghats mountains taper from high montane grasslands through deciduous forests into lowlands flanked by the Cumbum Valley in the south and the tributaries of the Kaveri River in the north. Reforestation is conserving ground water that feeds the rivers and people living downstream. The trees also protect some interesting wildlife. Bison, leopards and elephants pass through the forests, as Raveendran explains in this interview on YouTube with Francoise Remington, founder of Forgotten Children.

For more information, please see PHCC’s web site.

Palni Hills apiculture in pictures

Photo courtesy of Kannan Raveendran

Photo courtesy of Kannan Raveendran

Photo courtesy of Kannan Raveendran

Photo courtesy of Kannan Raveendran