From my home in Puerto Rico, the Caribbean archipelago where I was born and raised, the reality of climate change and its associated social inequities has hit me hard. Puerto Rico is subject to some of the harshest impacts of climate change. We see more frequent droughts, heat waves, floods and tropical storms, all of which are projected to worsen with rising atmospheric temperatures and warming oceans. Compounding the hardship, each disaster triggers additional challenges such as property damage, power outages, limited access to water, food insecurity, and changes in biodiversity to name a few.

Underserved communities, including many in Puerto Rico, experience the impact of climate change more severely. Marginalized groups are often not prioritized when it comes to disaster response, and many lack the means to invest in strategies, goods and services that can mitigate or support their recovery from natural hazards.

Yet as an innovator, I cannot help but to believe that we can tackle many of these obstacles through problem solving, creative thinking and equitable design. We need to act now and we need to put together as many heads as possible.

Over the past years, I have been navigating the intersection between climate change, technology innovation, and community impact in Puerto Rico and abroad. Alongside many great partners, I have facilitated collaborative design processes with residents of local communities, and have co-created hardware and software tools to address some of the indirect impacts of climate change. In the following pages, I will share a few insights that I’ve gathered along the way, and that I believe will be useful for anyone wishing to embrace design and engineering for climate resilience, with a community-based approach.

Incorporate community leadership and inclusive design

Humanitarian and community engineering projects can sometimes provide a cure that’s worse than the disease. The aphorism often applies when outsiders to the community take the approach of solving problems “for” the community, as opposed to supporting grass-roots initiatives or working hand-in-hand with local residents. Community leadership – not just participation – is key for the appropriateness, ownership and long-term sustainability of community-centered projects, and it avoids harmful outcomes to residents who can already be in a susceptible position with regards to climate hazards and socio-economic circumstances.

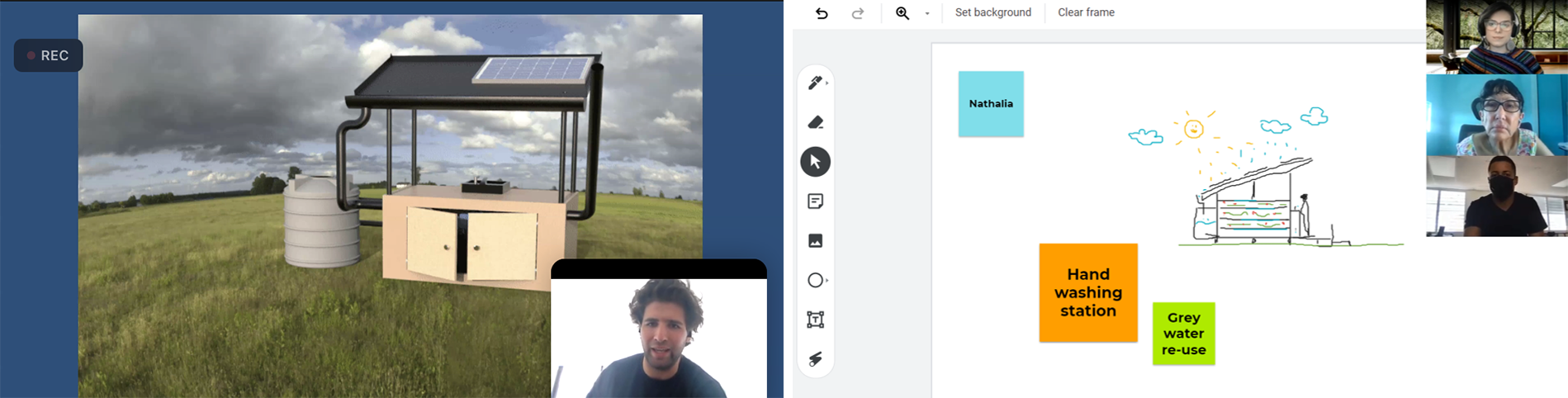

During our 2020 virtual Co-creation symposium, Puerto Rican community leaders and residents identified collective priorities and ideated solutions to strengthen their community resilience. Images show the conceptual design of an off-grid hand-washing station in Culebra, Puerto Rico. This project has been continued in partnership with Mujeres de Islas, Inc., Sede de Experiencias Vivas de Aprendizaje (SEVA), DesignED4Resilience, students from University of Puerto Rico and MIT D-Lab.

Moreover, specific populations within these communities, such as women, members of the LBTQI+ community, elderly, people with disabilities, children, and caretakers, tend to be over-burdened or at higher risk with regards to climate impacts. The domestic loads imposed by gender norms, lack of access to adequate health, transportation and communication services, heightened risks of sexual assault during disasters, among other factors, create particularly harsh scenarios for vulnerable populations. The first step towards aiming for responsible design is acknowledging these inequities and prioritizing accordingly. This mindset must be present throughout the design process – including the early research, data gathering and problem selection phases.

When engaging in community-based engineering projects, ask yourself: Which voices within my communities are present and which are not present in research and decision-making processes? How can we facilitate the participation of underrepresented groups? Do we have diverse leadership and design teams? How can our designs be culturally appropriate? Can our processes and innovations creatively adapt to different levels of literacy and technological skills? Can they aim for more equitable life experiences?

Virtual events during the global pandemic can easily exclude groups with low technological literacy. Several of our participatory design projects address this gap in representation through carefully performed socially-distanced activities. Some of the strategies we have used are: (left) a three-dimensional “Lego” model with 3D-printed parts that can be easily disinfected for use in a socially distanced community mapping project, (right) providing disinfected supplies for sketch-modeling and co-designing products, and, not pictured, large posters for distanced product feedback interviews.

Protect Natural Ecosystems

When I returned to my favorite bike path in the north-west coast of Puerto Rico after the passing of Hurricane María in 2017, I was devastated to see the beautiful mangrove forest completely destroyed. This shocking scene however, was only a testament of nature doing its job: the mangroves sacrificed themselves to protect the rest of us from the blows of the storm.

If we turn to mother nature, we will learn that she has already developed effective strategies for mitigating climate impacts. Mangroves, wetlands, and healthy coral reefs can protect us from floods caused by coastal erosion, storm surge or heavy rains. Healthy soils prevent flooding by filtering and retaining water, and they also capture and store carbon. Similarly, forests remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, and can mitigate the impacts of heat waves. We even have some help with vector control – one of the main concerns after heavy rains – as some fish species are natural predators of mosquito larvae.

Mangrove swamp at Punta Tuna Natural Reserve, not yet recovered from the impact of Hurricane María in 2017 (Maunabo, southeastern Puerto Rico).

If you are hoping to tackle climate challenges through innovation, try borrowing ideas from nature’s response. Ask yourself: How does nature solve this problem? Can we use or imitate nature (biomimicry) when addressing this issue? What is threatening the conservation of the natural ecosystems and biodiversity that protect us from it? Can we think of innovative solutions to protect or restore these systems?

In collaboration with researchers from the University of Puerto Rico and Comité Pro Desarrollo de Maunabo, Inc., and with sponsorship from the National Geographic Society, we are developing a low-cost electro-mechanical instrument (left) to support the research and conservation efforts of the Annona glabra juvenile plants in the Punta Tuna wetland in eastern Puerto Rico (right), and to promote citizen science within the neighboring communities.

Think Local. Think Analog.

“It took me five days to get to my parents’ home after the hurricane. I got a little further each day on my motorbike, clearing the path as much as I could from all the debris, returned home to get more gas, and got up to continue the next morning.”

My friend from rural Las Marías narrated his journey to check on his family after Hurricane María. This is the reality of many communities that are devastated by a natural disaster. Residents are unable to leave their community and seek external services or supplies, and family members or other groups cannot enter the community to provide support. When developing technology aimed to support post-disaster scenarios, we should not assume there will be a working telecommunications infrastructure, open roads, functioning supply chains, electrical power supply or running water. While this may seem like a limitation, these constraints may actually be key to coming up with creative solutions that we wouldn’t have thought of otherwise.

When faced with resource constraints, try focusing on all the assets that are available. Which materials are commonly used and readily available? How can we untap naturally abundant resources? What are some of our community strengths? Can innovations be designed around commonly used devices or practices? Are there any traditions or cultural traits that would come in handy? Who are the community experts in local skills, activities or crafts? What strategies can we learn from communities living in remote locations and contexts – such as nomad populations and indigenous groups?

After Hurricane María, I was impressed to learn about all the different gadgets that people came up with to manage the emergency. Makeshift washing machines, do-it-yourself showers, rocket stoves, you name it. It’s amazing how creativity can flourish when we are forced to look for alternatives. With no power for months, many people began using their grandparent’s technology – washboards, radios, land-lines, hand drills. Even horses were used to cross flooded roads! Sometimes, we discard “outdated” technology as obsolete. However, we may want to include these analog tools in our brainstorming board as they may trigger innovative ideas for resource-constrained scenarios.

Break down your design challenge into the different functions you need to achieve. Which are the potential paths that can be taken to fulfill these? Can we use hand-cranks, foot-pedals, or solar power to operate machines? Are there alternative communication methods? Can we incorporate redundancy in our solutions and have multiple options? How might we harness the users’ own creativity through our design?

After hurricane Maria, community residents in Puerto Rico came up with makeshift solutions to manage the emergency (left), harnessing this creativity, and in collaboration with the Response Innovation Lab, we conducted workshops focused on do-it-yourself technology, such as foot-powered bucket hand-washing stations (right).

Think outside the crisis

“Hope for the best, prepare for the worst” is one of those phrases we frequently hear when it comes to disaster preparedness. We don’t know exactly when we will be hit with the next serious heat wave or if a dangerous storm will make landfall this year. Many climate stressors are seasonal and unpredictable in nature. While experiencing the event, the need for actions and solutions will feel urgent. But what about the rest of the year when we are not experiencing this? What will happen to our projects, initiatives, businesses and innovations? How will they be maintained and sustained outside the crisis?

Imagine this scenario: your community has formed a climate action committee and decides to install a solar charging station in preparation for the next power outage – everyone is excited! After two lucky years, the first major storm causes a community-wide blackout, and everyone rushes to the station – only to find dirty and damaged solar panels, families of pigeons who made it their home, and ultimately a useless device that will now become solid waste in the community. The group has become inactive, so there are no established roles or response plan.

What if the story had been different, and this charging station had been placed in a local school, to be used by youth during the school year? Perhaps any damage would have been identified early on and fixed by troubleshooting. What if the climate committee was actually a student group that organizes monthly activities? Perhaps everyone in the team would be ready-to-go after the power outage.

It’s important that sustainability, and better yet, prosperity and regeneration, is considered during the early phases of project planning. Ideally, project continuity should be budgeted for when allocating funds early on. Otherwise, we may run a hackathon, start a project, or perform research, only to leave a project unfinished and people disappointed. In disaster scenarios, community groups (many of them in strenuous financial circumstances) constantly invest their precious time with students and organizations, usually uncompensated. After hopes are raised, events finished, and papers published, many of these projects are not completed as expected, the community never hears back, and it is difficult to regain trust for future collaborations.

When planning climate and community-centered innovation, I encourage you to challenge your vision and ask yourself: How can our innovation add value outside of the crisis? Can we build something that harnesses other opportunities or serves multiple purposes throughout the year? How will our project or business be sustainable in the long term? Which partnerships can we leverage to support continuity? How will we follow up, measure and evaluate?

It’s not all about nuts and bolts (take care of yourself)

And finally – abrupt changes to our normal conditions, like being exposed to natural disasters, can take a serious toll on our mental health. Evoking memories of past events, or discussing potential future hazards, can cause stress, anxiety and traumatic response throughout design and innovation processes. Being fully submerged in climate action activities can also become draining and stressful.

Take a deep breath.

Don’t put unnecessary pressure on yourself and others. Enjoy the process, the community, the mutual support, the energy. Remember to be present, to feel the sun in your skin or the rain on your face. Avoid overworking and look for ways to clear your mind and to manage stress. Acknowledge yourself, your community, and your team. Keep in mind that an important area that is strongly affected by climate change is people’s mental health. Can our design processes, and our designs themselves, acknowledge and support the mental health stressors that are provoked by climate impacts?

Breathe. Take care of your inner peace first, so you can radiate contagious positive energy outwards.

Enjoy innovating!

How to get involved

Are you interested in innovating for climate resilience or disaster response with a community-centered approach? Hoping to get involved in Puerto Rico? Here are some groups you can reach out to:

- Sea Grant Puerto Rico

- Centro Interdisciplinario de Estudios del Litoral

- American Red Cross, PR chapter

- Para La Naturaleza

- Puerto Rican Non-Profit Organizations (Directory)

- Planet Centric Design

- UNDP Accelerator Labs

- PamLab Design and Engineering (that’s me!)

About the author

Pamela C. Silva Díaz is a mechanical engineer and owner of PamLab Design and Engineering. Through her business, she offers engineering and technology design services, as well as consulting on community-centered engineering and participatory design processes. You can reach her at pamela (at) pamlabdesign.com.