Enter the Innovate for Impact: Siemens Design Contest to solve post-harvest loss challenges like low-cost food refrigeration.

Puerto Rican farmers are spending grants from the food aid non-profit World Central Kitchen to build their own walk-in coolers to reduce post-harvest food losses. Their next challenge is low-cost refrigerated transportation. The technologies they are motivated to build themselves suggest needs that product designers and engineers could meet. For design inspiration, try looking for these kinds of examples of do-it-yourself builds and bootstrapped workarounds that solve problems affordably.

Small-plot farmers in Puerto Rico are struggling to meet new regulations that preserve food safely and reduce post-harvest losses. Grants by the non-profit food relief organization World Central Kitchen have helped some of the island’s farmers bring their operations into compliance, but mainstream methods of construction and equipment purchases can cost more than even the grants provide. So, some grant-winning farmers are building their own coolers and regulating the temperature with mobile-connected sensors. Others are rent-sharing to work around the high cost of refrigerated trucks.

Affordable, sustainable transportation is still an unmet need. So, too, are affordable walk-in coolers.

New regulations and a helpful non-profit

The US Food and Drug Administration issued new regulations to farms called the Food Safety Modernization Act. The act went into effect for small farms in January 2020. As a US territory, Puerto Rico must comply. Small-plot farmers on the island often work within slim profit margins, and some operate in the red.

World Central Kitchen provides food aid, trains cooks and supports small food ventures in Latin America and the Caribbean. Chef José Andrés founded the non-profit in 2010 to bring food relief to Haiti following that year’s catastrophic earthquake. In Puerto Rico, World Central Kitchen launched a program called Plow to Plate and has awarded (USD) $1.3 million in grants of $5000-$20,000 to farmers, fishers and small businesses in the food industry since December 2018.

“The farms are where we have helped support the development of cold-storage facilities. Because Puerto Rico is so hot and humid, when you pick something, in a couple of hours it might be wilted,” Alexandra Garcia, World Central Kitchen’s Chief Program Officer, told E4C. “You can’t keep stuff for more than a few days,” Ms. Garcia says.

The mainstream solutions are costly. Companies have offered custom and prefabricated cold storage units. Some are solar powered and mobile-connected, but the problem is their price at $60,000 or more.

“Some of our farmers gross as little as $30,000. I’m sorry, but farmers are not going to be buying $60,0000 storage units when they can build their own.” Ms. Garcia says.

“Farmers tend to be DIY hackers. They fix tractors, they know how to fix the barn, they’re kind of jacks of all trades,” Ms. Garcia says. “They can build a cooler for as little a $2000-$5000.”

Cold transportation has been a harder problem to solve. The farmers in the Plow to Plate Program have not yet found an affordable technological solution. World Central Kitchen would like to see new ideas from product designers and engineers.

“How can engineers design some system that can transform a pickup or a jeep into cold storage transport?” Ms. Garcia asks.

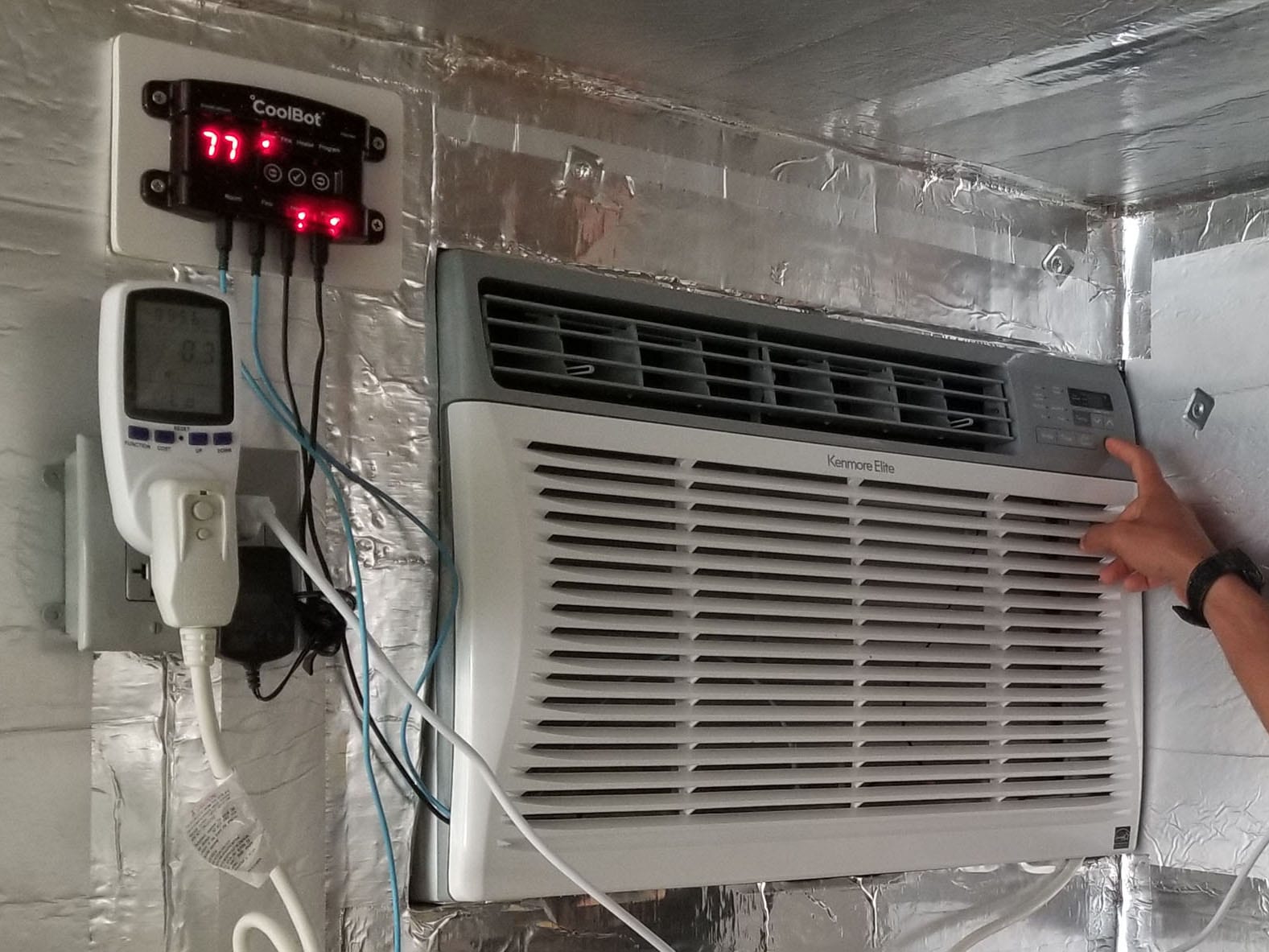

CoolBot, the linchpin in DIY walk-in coolers

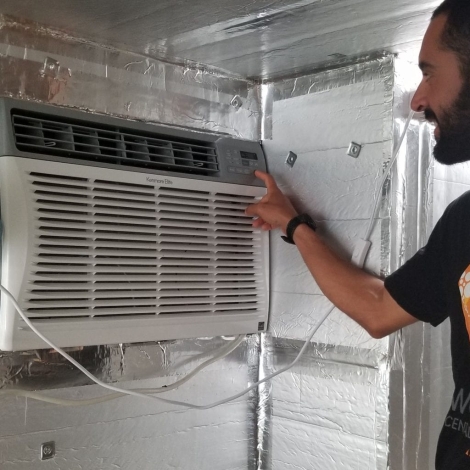

Photo courtesy of Franco Marcano

Farmers who have been making their own walk-in coolers use CoolBot temperature regulators, Ms. Garcia says. Hook a CoolBot up to a box or window air conditioner in an insulated room, and the Coolbot can maintain the temperature at the desired setting. The device has a microcontroller brain bundled with sensors to take the room temperature and keep the air conditioner in working order. It prevents the air conditioner’s fins from freezing. Store It Cold, LLC, CoolBot’s US-based manufacturer, also makes fully functional walk-in coolers. One of them is featured in E4C’s Solutions Library.

See the CoolBot walk-in cooler in E4C’s Solutions Library

Franco Marcano built his own walk-in cooler on his farm Cosechas Tierra Viva, located near the eastern coast of Puerto Rico. Mr. Marcano cultivates two-thirds of an acre on his 1.5-acre property, leaving the rest as fruit trees and forest. His harvest is mostly greens, such as kale, bok choy and arugula, which he sells in bags at farmer’s markets around the island.

A $9000 grant from World Central Kitchen paid for materials, and Mr. Marcano built the cooler and other infrastructure himself.

“I built a fully equipped post-harvest station that complies with the latest FSMA regulations. Stainless table, walk-in cooler, sink, hot water. Everything we need to make sure that we can prove to our buyers [that the produce is safe and compliant with regulations],” Mr. Marcano says.

Money is tight for the business, as the farm has operated in the red since its start in 2014. Mr. Marcano has put his mechanical engineering degree to work on DIY construction and technological upgrades for the farm. He is trying to cut costs while laying the groundwork for the potential of a financially sustainable business in the future.

When he learned that he would need a walk-in cooler for his greens, Mr. Marcano priced new and used options, but they were too expensive. Used coolers he saw cost $3000 to $4000 for just the insulated box, not including the compressor or other components. New ones cost $10,000.

“At the end it’s just a box with insulation,” Mr. Marcano says. He decided to build his own. “I built a 17 by 8 [foot] walk-in cooler, and with all materials it cost around $3000,” Mr. Marcano says.

The CoolBot is the brain of the cooler, and it’s an awesome device, Mr. Marcano says. His unit came with instructions for how to build a walk-in cooler. He built his cooler in a corner of his basement for added insulation underground. As an engineer, he was of course compelled to make custom modifications to the design. For added strength and ease of clean up, Mr. Marcano framed the cooler with galvanized steel rather than wood, and hung PVC panels rather than drywall. A 12-BTU window air conditioner chills the room to 50 in 15 minutes, Mr. Marcano says.

“I’ve been trying to share with other farmers that I built this humongous walk-in cooler for a fraction of the cost of what it would be if you went to the market for a walk-in cooler,” Mr. Marcano says.

The CoolBot Mr. Marcano uses is an older model that, unlike newer generations, does not connect to a mobile application. To compensate, and to complement the device’s sensor suite, Mr. Marcano has mounted sensors of his own.

“We designed a remote humidity and temperature sensor. It’s Arduino based. Raspberry Pi, C++ and Python. I use open-source, open-hardware technology to develop simple things that just make my life easier,” Mr. Marcano says.

Like the cooler, the entire farm is studded with sensors.

“We have developed a model called smart farming,” Mr. Marcano says. The farm has a weather station that gathers data on that unique micro-climate and sends it to a database for access from a home computer.

“We can record precipitation, wind speed, temperature, humidity… We can control irrigation though an app, know how much water is in the tanks, how much we’re consuming. We try to correlate our data with production data and come up with strategies about what to grow and when to grow it,” Mr. Marcano says.

“We’re trying to go back to the land to live a simple life, but yet we live in the 21st century and we cannot deny that technology can make things simpler,” Mr. Marcano says.

Refrigerated transportation: a target for good design?

Puerto Rican farmers take foods from their farms to markets located in different spots around the island. To keep their products intact and sanitary, and to comply with FSMA regulations, they need refrigerated transportation. Mr. Marcano has considered DIY options.

“If I can get ahold of a vehicle, I can easily put insulation boards around it,” he says. Then he might add a refrigeration unit of some kind attached to a battery.

Photo courtesy of Maria Teresa Juan

Other farmers have taken to rent-sharing arrangements. Maria Teresa Juan, owner of Urrutia Foods, pays her part of a $325 fee to rent a refrigerated van with another farmer. Six times each month, Ms. Juan loads up goat and cow cheese, honey and coffee and shares space with the other farmer’s eggs.

Before the new regulations took effect, Ms. Juan was able to store her cheese in coolers that were passively chilled, but now she is required to use refrigeration while moving the products to market.

Rent sharing is just one means of cutting costs and turning a profit on Ms. Juan’s farm. The Hacienda Renacer comprises 110 acres that Ms. Juan has rented for 20 years. She needs five acres for her goats and rents the rest to cattle ranchers. The honey, coffee and cow cheese she sells are produced on other farms, and she sells them through an arrangement organized in a cooperative.

“That’s how I’ve figured out to keep my project going while I become financially sustainable,” Ms. Juan says.

In 2019, supermarkets declined to stock Ms. Juan’s goat cheese because its packaging was not compliant. The cheese required modified atmosphere packaging that displaced oxygen inside the package with nitrogen. Ms. Juan needed a nitrogen injection system, which she was able to afford with a $20,000 grant from World Central Kitchen.

Photo courtesy of Maria Teresa Juan

Now she needs refrigerated transportation.

“I tried to buy one, but the cheapest I found was a used truck for $30,000. There was just no way I could afford it. Refrigerated units don’t arrive to the island as much. Sellers, I think they take advantage of that,” Ms. Juan says.

Low-cost refrigerated transport might have a large market in Puerto Rico. As many as 70 percent of the farmers on the island rent vans, Ms. Juan says.

A desgned solution would have to operate during drives of 10 minutes to up to 2.5 hours, and it should keep its contents cold for six hours while parked at the market. The vehicle should also continue operating on the drive back to the farm.

“A successful market is one where you come back almost empty, but not entirely empty,” Ms. Juan says. An empty truck implies the loss of sales that might have been made if more of the product had been stocked.

A dire need

If farms fail to comply with the new regulations, they will have to close their doors. Closures may be inevitable at this point. Ms. Garcia says. World Central Kitchen’s work may be a lifeline for some, but others will need other kinds of help.

The cooler upgrades that Puerto Rican farmers have taken on themselves, as well as the lack of low-cost refrigerated transportation, both suggest potential targets for engineering design and social entrepreneurship. New low-cost products and services could meet a dire need in Puerto Rico.