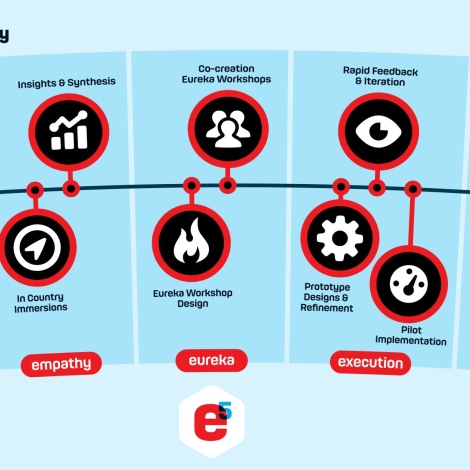

Human-centered design is a process as fluid as the humans on which it is centered. But it is also a methodology that is simple enough to lend itself to a flow chart. Matchboxology is a South Africa-based consultancy firm that applies the principles of human-centered design to improve technologies for global development. They have distilled their Africanized human-centered design process into five phases, each of which begins with the letter “E.”

Two heads of Matchboxology joined us to illuminate the phases. Cal Bruns is the founder, CEO and Chief Creative Incubationist at Matchboxology, and he is joined by Cristin Marona, Director of Positive Change. Mr. Bruns has 30 years of experience in design and behavior change strategies in more countries than some people can name without consulting our phones. Ms. Marona may have accrued a similar number of stamps in her passport while working for more than 15 years in global public health, social work and development. She is based in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, working on projects throughout Africa. She is also an Adjunct Professor at the Boston University School of Public Health and a doctoral candidate at the London School of Tropical Medicine.

They both agree that a traditional product design team tends to focus on a product’s attributes and characteristics; whereas human-centered design begins by gaining an empathetic understanding of consumers’ needs, preferences and realities before the design process begins. “This is especially true in the context of global development, Mr. Bruns says.

“International development deals with really hard problems, but both [fields of design] have technical and human challenges. Unlike typical fast-moving consumer goods design challenges, when you get it wrong development, people die,” Mr. Bruns says. “There are, unfortunately, too many examples of potentially life-saving innovations that don’t save people’s lives because they started with a technical solution in mind, not the human problems that lie behind the challenges.”

Phase One: Evidence

The first phase of human-centered design calls for gathering evidence. By carefully examining a robust body of scientific evidence, designers can start to discover where the real problem they are trying to solve lies.

“The magic of science is it’s good at focusing your attention on where you should be looking,” Mr. Bruns says. Quantitative data can point to a problem but qualitative interrogation can begin to reveal causes.

One of Matchboxology’s recent projects tries to encourage the use of HIV self-testing kits and reduce HIV transmission amongst Kenyan men, an effort funded by Children’s Investment Fund Foundation, the Elton John AIDS Foundation and UNITAID. The work began with gathering evidence.

Data show a 6-7 percent HIV-positive rate in the population. But many people do not know they are positive, and most of those who don’t know are men.

“Conventional research indicated that men don’t want to access services because they don’t want to go to clinics,” Ms. Marona says. She and her team were unconvinced this was the only reason, and dug into the issues of stigma and HIV. As opposed to fielding surveys, they hosted conversations in peoples’ homes, coffee shops and other comfortable locations to build trust. Instead of one-on-one interrogations, they spoke with groups of friends to help people relax and open up. In all, they met with 94 men and more than 100 women.

“Without that context of the wider network you’re really missing a lot of what’s going on,” Ms. Marona says.

Men, they discovered, worried about things like what their wives would think if they came home with an HIV testing kit. What would it say about their marriage? If they test positive, what would that say about their ability to provide for the family? Ultimately Matchboxology clustered HIV testing barriers into six categories of fears men have. With that evidence, Matchboxology could move on to other phases of human-centered design.

Phase Two: Empathy

“In our workshops we ask people to take off their right shoe, hand it to the person next to them and ask them to put it on. We do it with everyone: diplomats, people in rural villages, women and men. Everyone laughs because it’s uncomfortable to wear someone else’s shoe. But then it sinks in and they get the importance of empathy in problem solving,” Mr. Bruns says.

Empathy-building activities can help well-meaning designers discover that they might not have the right idea at the outset.

“A lot of people who want to solve the world’s toughest problems are really brilliant,” Mr. Bruns says. “However, they assume that once they have arrived at a solution, everyone will rush to it. By sharing and building empathy for those closest to the problems, a brilliant technical designer’s problem-solving abilities are enhanced.”

Phase Three: Eureka

Collective problem-solving workshops are “where the magic happens,” Mr. Bruns says.

“When you listen to people, they’re going to tell you some really interesting shit. We tell designers, don’t rush to sell your preconceived solution, let people speak first,” Mr. Bruns says.

The ‘aha’ moment happens when technical experts, designers and those closest to the problems are really listening to each other as equals. This is the ignition of co-creation, “the most powerful moment in human-centered design,” Mr. Bruns says. The firm has conducted ‘eureka sessions’ all over the world, seating people such as officials in Brazil’s ministry of health beside patients and nurses working in the favelas. When experts see how smart and creative ordinary people can be about their own lives, they can become humble and open to new ideas. That’s when “they give us their nuggets of goodness,” Mr. Bruns says.

“What happens when the design experts are in these meetings is they realize the limitations of their first prototypes,” Mr. Bruns says. “We so often see the go-to solution is an app, but that’s not always practical in areas where data is limited or expensive or almost nobody has smart phones.”

On the other hand, “Village guys see things every day and don’t recognize them as opportunities, but the technical guys see with fresh eyes and plenty of expertise and can help prototype those out,” Mr. Bruns says.

Eureka sessions lead to the next phase: Execution.

Phase Four: Execution

Executing the design merges the work of the first three phases. A great design hits a sweet spot between what people want, need and can actually use.

One of the solutions Matchboxology fielded in the HIV self-testing project was to enlist moto-taxi drivers as distributors and salesmen. Riding on the back of a motorcycle taxi, male passengers could discuss their issues in privacy with the male drivers. The drivers could use that opportunity to convince their passengers of the need to test. It’s the kind of plan that could only follow from a deep understanding of the reasons why men avoid testing.

Phase Five: Evolution

As the solution propagates into the wild, its strengths and flaws appear. Refined ideas and new courses of action suggest themselves, leading human-centered designers to pursue improvement. The fifth phase, evolution, is where designers get better at solving a problem.

In this phase, it may become clear that one product or one strategy is useful among some people, but problems persist.

“How can we get to a greater bouquet of products,” Mr. Bruns asks. “How do we know we need a bouquet? Evidence tells us.”

Matchboxology’s bouquet of products to increase HIV testing in Kenya included camouflage bags to hide the kits while you transport them home from the pharmacy and “sex packs” in bars that include condoms and couple’s self-testing kits.

Parting advice: be humble

“If I was going to give some advice, I’d say increase your humility and be objective,” Mr. Bruns says. He mentions the example of communities in sub-Saharan Africa in which women carry water jugs from rivers to their homes. People in the global West saw it as a water and a gender problem; convinced that putting wellpoints in the village would solve both. When wells fell into disrepair, human-centered designers looked beyond the mechanical issues and discovered that women valued the time they had to themselves walking together to and from the river to fetch water. Many were quite happy to return to their old ways.

“Experts worked on solving the problem without recognizing all the dimensions,” Mr. Bruns says. “you need to understand the full reality before trying to change it.”

Expanding on the suggestion, Ms. Marona emphasizes the value of listening.

“You have to meet people where they are, and part of that is understanding their mindset,” Ms. Marona says. “If you’re parachuting in a solution for them, you’re sort of setting yourself up for failure from the beginning. Did you ask what they want?”

This article again exposes us to the central dilemma. As practitionars, we have those who develop communities and those who develop economies. Community Development arises from a completely different worldview than does Economic Development.

The former is driven by the needs of people. The latter by the wants others would impose upon society. Marketing seeks to take wants and turn them into needs. This is Econ101. Wants are turned into societally endorsed personal needs. Inevitablly they can be identified by examining their genesis and seeing where they have not followed methodologies exemplified by the 5 E’s described here. The potential Achille’s Heel in this methodology, given that it inevitably is implemented in a world dominated by the ‘Want-centric’ worldviews, lies in its very first step at the point where data available leads to the “alignment of [the project’s] definition of success” . If external funding sources are sought after having defined the project in this way, in most instances one can expect the project to have set itself up for failure through the barely perceived but significant pressures to describe success in terms of Economic Development rather than thaose of Community Development. Good business rather than good living.