The hardest question that Erna Grasz has answered came from a young man in high school in a rural Kenyan village, Grasz says. He asked her why she quit her job as an electrical engineer to become a beggar. As the CEO and founder of a non-profit organization, Grasz spends a lot of time holding her hand out for donations. Or “begging,” from this boy’s perspective. She did it because there were people in her life who cared who didn’t have to care, she told him. She was the first person in her family to earn a university degree, and she did it because teachers, Girl Scout leaders and the community supported her, she says. That education led her to a career in robotics for removing landmines, radioactive waste and bombs and managing teams of engineers at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and Philips Healthcare.

Now she pays the favors forward. Grasz quit her corporate job to found the Asante Africa Foundation in 2006. Together with Emmy Moshi, a Tanzanian entrepreneur and Helen Nkuraiya, a Kenyan school principal, and an international team in three countries, Grasz helps provide meaningful education for children in rural Africa. To date, Asante has partnered with 26 schools, works with 660 teachers and 30,000 students. Grasz and her team build schools, kitchens and dormitories, install plumbing and improve sanitation in the communities where they work. They provide scholarships for students and training and resources for teachers. And they work with and hire people from the communities where they operate.

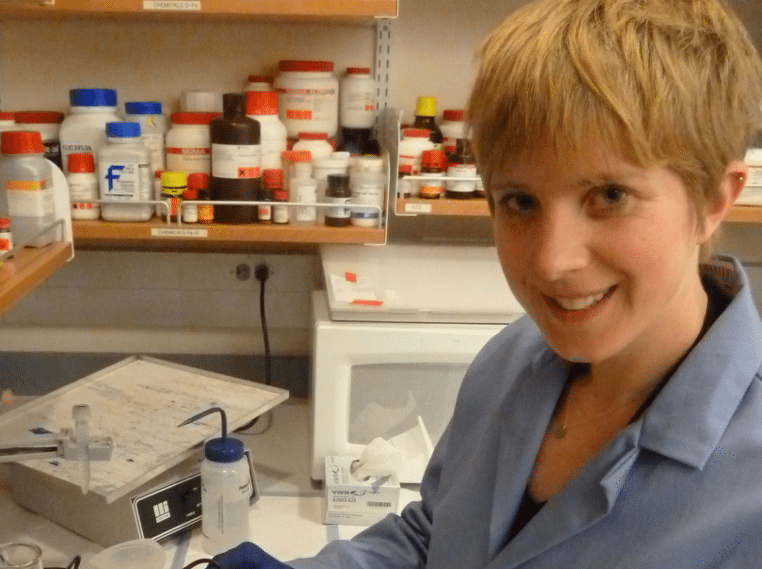

Grasz volunteered the answer to her hardest question ever, so we asked her five easier ones. This is five questions with Erna Grasz.

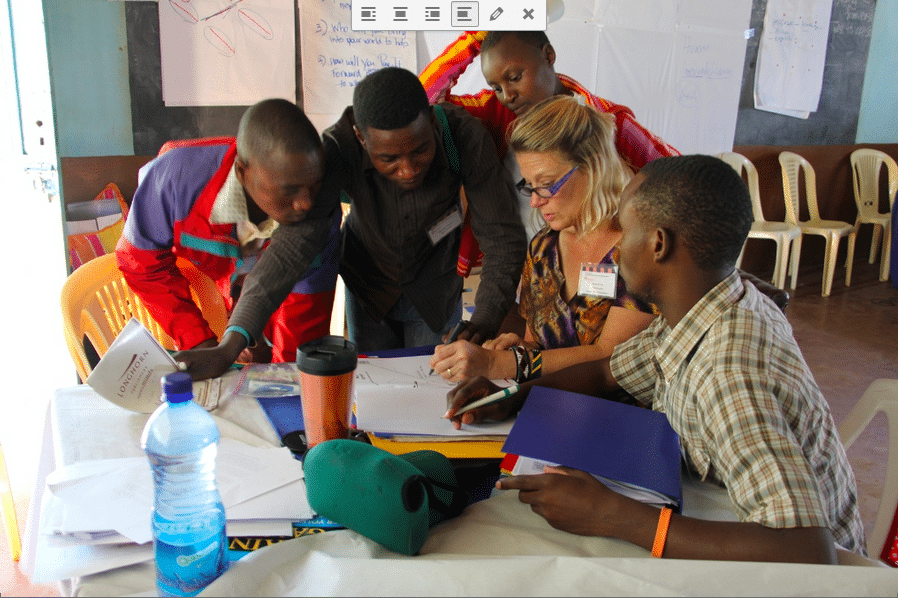

Erna Grasz shows Kenyan students how to set small goals to reach larger ones. Image courtesy of Erna Grasz

E4C: What were you doing when you first realized that you are in the right line of work?

EG: I was probably in my early 30s when I finally realized the power of engineering. And I was leading a team of engineers, we were building an automated robotics facility that nobody thought was even achievable. And it was in the moment that we commissioned this optics facility, fully automated, that it made me realize, dreams really are achievable if you can bring the right talent together and if you can help all of these talented people see what the vision looks like. If they can see it in their head, the impossible is achievable.

I worked at Lawrence Livermore National Lab. At the time we were working on the world’s largest laser. And it still is. My boss said you’ll have to build a class 100 clean room that’s going to assemble all of these optics and, oh, by the way, you’ll have to use robotics to do it.

And I remember saying to him, ‘what’s a clean room?’ He said, ‘go figure it out.’ And then he said, ‘there’s no money in the budget, you’ll have to go to Washington DC to get the money.’ And I remember thinking, How are we going to do this?.

So we rallied a team. We built an amazing team of engineers and designers and five years later we delivered. we delivered on time and met the specs. I knew then and there that engineering and technology makes the vision that’s in your head a reality. You can do it. It’s not easy, and you’ve got to keep getting back up when you fall down. But you can do it.

I think the world of robots symbolizes what I love about my job today. In the world of robotics, if the software doesn’t work with the mechanical, doesn’t work with the electrical, the optics, the operator – if those piece parts don’t work cohesively, you won’t get a working solution. And in my world today, if the community is not in sync with the donors, is not in sync with the technology, is not in sync with the teachers – none of it works. So, in my mind they’re all systems challenges. They’re all systems solutions.

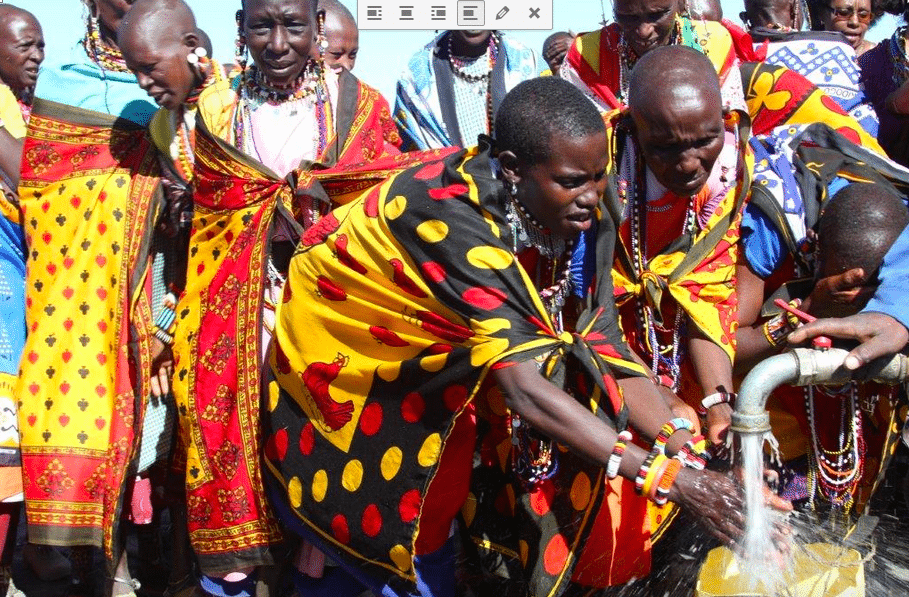

So, how do I know I have the most amazing job in the world? It was a year ago, standing in the bush in Kenya, there was an elder, a Maasai chief elder who said he had never seen clear water come out of the ground. We were there to honor and celebrate a new well at his school and new classrooms. And the community had never seen clear water before. I knew I was in the right job when everybody is expressing how their life was going to be different because they don’t have to walk 20 kilometers to get water. And the kids will get lunch because there’s water to cook the cream of wheat. I just paused in the moment and thought we had just changed a community of 7000 people because of this one small technology. [Editor’s note: The well installation was in the Nchaishi community near Maasai Mara]

Members of the Nchaisi community in Kenya use a water spigot that Asante Africa installed. Image courtesy of Erna Grasz

E4C: How important is technology and infrastructure to education in the communities where you work?

EG: I have seen good technology and I have seen bad technology. There’s actually a saying in Africa: Africa is a graveyard of good ideas. I have seen a lot of outsiders carry a widget and say, ‘this is going to save your life. This is going to change your world.’ And no one bothered to ask, Is this even what you need? I see it all the time. I had a headmaster say, ‘no I don’t need another water tank. I have four water tanks, but no way to get the water into the tank.’

I’ll give you a great example right now. Everybody is wanting to dump Kindles and iPads into schools in Africa. No electricity to charge them, no Wi-Fi to download curricula. No instructions on what a touchpad means. It’s a cutting board as far as they’re concerned. So, if they haven’t bought into it and the user doesn’t understand and buy into what the purpose of it is, then it’s bad.

Good technology is when it’s simple, serviceable, usable and it’s their idea.

Mobile phone apps are a great example. What is magical is what’s going on right now. Last December I was in a room with 120 highschoolers. I asked them to raise their hands if they have a mobile phone. There were only three kids who didn’t have a mobile phone. A Maasai chief said to me, ‘Erna, do you know how we know where there’s green grass for our cows?’ And I’m expecting a divining rod or something. And he says, “We call our friends on the phone to ask.”

Phones are used as banks. People actually load money onto their phones and use their phones to share it with each other.

It’s clever how they’re using simple technology to leap frog the computer era that we’re in here. They won’t ever know computers like we do.

E4C: You have worked in robotic mine detection and radioactive waste removal, but now you’ve gone off the rails to work in education in developing countries. Does your former life instruct your work now in any way?

EG: A lot of young people will say to me, ‘I want to leave engineering, I want to run a non-profit.’ So what I tell people is that I’m only just now getting prepared to do what I’m doing.

The example that I give is that when I was leading engineers at Philips Healthcare I had engineers that lived in Bangalore, Maine, Cleveland, Ohio, California and Holland. If I had not had to do the job I had orchestrating how all of those people work together virtually, and how as a manager and leader I would lead virtually, I would not have been prepared for this job.

I’m a firm believer that the world you’re exposed to today is giving you tools in your tool kit for what you’re going to do tomorrow. Sometimes that’s technical tools, sometimes project management, sometimes people skills but they’re all getting you ready for what’s coming.

E4C: What education technology have you seen in developing countries that you think should also be used in developed countries?

EG: I think what’s missing… I’m not sure how to say it without sounding insulting. Our youth here [in the United States] have so many tools and technologies to assist them that they have become dependent on those tools and technologies. They’re forgetting how to be clever and creative. What is going on in developing countries is that, because they don’t have so many tools and technologies, they are still very hungry for knowledge, they’re very creative and clever and determined.

So if I could, I would take them away [from students in developed countries]. I would turn off technology for a day and try to solve the same problems and just see how clever and creative the young people can be.

E4C: What mistake have you made in your work that has been instructive, and what did you learn from it?

EG: The mistake that I’m constantly making is assuming too much. I’m a story teller so I’m going to give you a story. We helped build a school in a community in Tanzania. The community had never written a check or paid a teacher’s salary or paid a cook to go buy maize. We were explaining that, as the community leaders, they needed to get a ledger because they already had all the receipts, but they didn’t have a ledger. So, six months later, I’m back in town and they show me the ledger. They pull out this ledger, set it on the table, they pull out their receipts, set them next to the ledger. They have a ledger, and what do you think, they open it up and it was empty.

So they had done exactly what they had been asked to do. But a lot had been lost in translation around what our assumptions were about what a ledger was supposed to do for them.

For us, that was a huge lesson. In order for the communities to be successful, they may need skill building and learning. And it’s probably not from some white person in the Western world, it’s probably from someone in their community who understands their culture. We find mentors in the community to help. We staff local, we lead local, we mentor local.

Westerners are not a part of the equation when we’re interacting with the communities. All of our staff that work with in Kenya and Tanzania are local people from those cultures.

I call it the inside out solution. If the solution is not coming from within it will not survive.