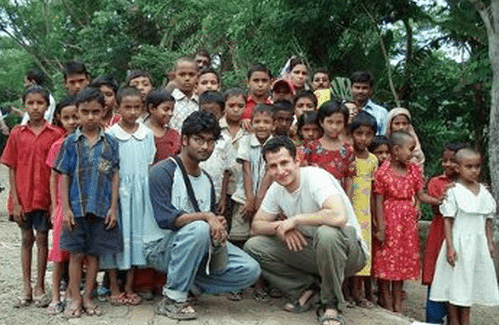

Josh Nesbit is helping to turn cell phones into tools for better healthcare. Photo courtesy of Josh Nesbit

The cell phone has been a lifesaver for patients in developing countries. It has improved people’s odds of getting help, and it has enabled more personalized medical care. Josh Nesbit has helped pioneer the push to expand the work of the cell phone in rural healthcare. In May, we retold Nesbit’s story of meeting rural healthcare workers who walk 45 miles to collect information on patients. Nesbit saw the problem during a visit to Malawi in 2008 when he was an undergraduate student at Standford.

Since then, Nesbit’s company, Medic Mobile, has helped hospitals in rural Malawi digitize their medical records and, using a text-message-based system, dramatically cut the time it takes them to track patients. We caught up with Nesbit between trips in his tightly packed schedule. These are five questions with Josh Nesbit.

E4C: What do you say to skeptics who believe that the value of the cell phone in international development might be over-hyped?

JN: Right now, the power of the phone comes from its ubiquity and not necessarily its features. The phones that are being purchased at scale in areas where the value to development work is highest are ultra-low-end handsets capable of texting, navigating SIM menus and calling. But the fact that this connectivity is the new lowest common denominator – that’s a game-changing platform and reality. I will say that I love the built-in flashlights in $12 phones!

E4C: SIM apps for collecting data with cheap phones is new, but in its testing phase. Have you had a chance yet to see the impact it can have?

JN: Great question, but we’re just now implementing the pilot in Malawi focused on community case management to improve child health. Pilots in a few other countries will follow in the next three months, and we hope to scale from there.

E4C: Would you mention how Medic Mobile uses these open source platforms: FrontlineSMS, OpenMRS, Ushahidi, Google Apps, and HealthMap.

JN: We’ve implemented and developed tools for FrontlineSMS, including the base platform, FrontlineForms (a java application for data collection through mobile forms that runs on specific mid-level handsets), TextForms (a tool to manage data collection through structured SMS exchanges), and PatientView (a lightweight patient and health worker records system, with a heavy emphasis on managing community-level data and services). We also built out the messaging module for OpenMRS, which is an enterprise-level, web-based medical records system.

HealthMap and Ushahidi are popular mapping applications – we’ve worked closely with the brilliant teams behind the technology but haven’t contributed code to date.

We collaborated with Google’s disaster response team on their development of Resource Finder, a dynamic resource mapping platform. SIM apps are our newest products, and we’ll have more to announce soon!

E4C: What has been the response to Hope Phones so far? Do people want these used phones?

JN: The campaign has really grown this year, and we’re seeing a jump in phones donated – both from the general public thanks to coverage from Good Morning America and other outlets, and specific campaigns such as Every Mother Counts, the Million Moms Challenge, and George Washington University’s commitment to collect 20,000 phones before they host the Clinton Global Initiative’s University meeting mid-2012. We’ve already delivered phones to health workers from Malawi to Senegal to Honduras, and expect to scale both collection and delivery in the first quarter of next year.

E4C: Can the E4C community help you with a project underway, or with the design of new phone tools that you might have in the works?

JN: We’ll never dissuade offers to help – if you see a specific need, have the ability to contribute code to an open source product, or have a big idea, please be in touch.