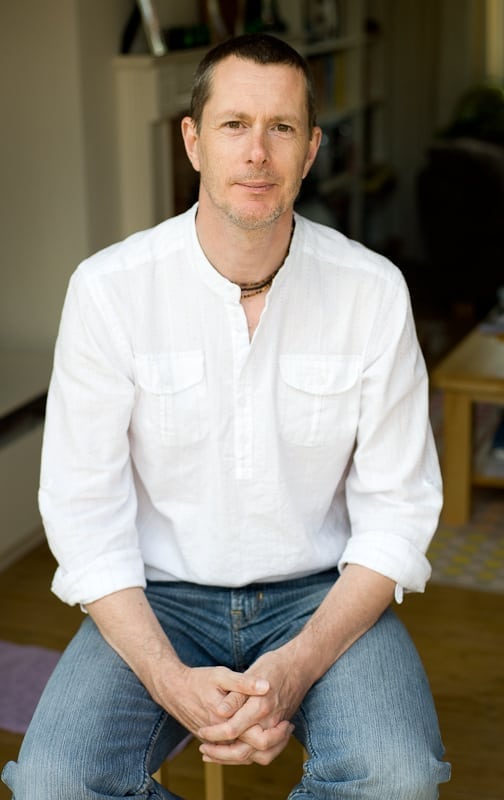

Ken Banks launched FrontlineSMS in 2005 as a tool that turns a computer into a hub that broadcasts text messages to mobile phones and gathers data sent by text. FrontlineSMS is open source and free to use, and it has been downloaded more than 200,000 times. The platform has been used to manage medical records, monitor elections, in finance and other settingBanks went on to found kiwanja.net to help people working in global development make the most of communications and information technologies.

Ken Banks launched FrontlineSMS in 2005 as a tool that turns a computer into a hub that broadcasts text messages to mobile phones and gathers data sent by text. FrontlineSMS is open source and free to use, and it has been downloaded more than 200,000 times. The platform has been used to manage medical records, monitor elections, in finance and other settingBanks went on to found kiwanja.net to help people working in global development make the most of communications and information technologies.

Banks is now the first Entrepreneur in Residence at CARE International. He has written articles for the BBC, the Guardian and CNN, and he is editor of two books: The Rise of the Reluctant Innovator (PDF book sample) and the recently published Social Entrepreneurship and Innovation: International Case Studies and Practice. We asked him five questions.

E4C: What trends in mobile technology are making an impact in global development?

KB: I think the most exciting thing about the technology is that it’s actually not the most interesting thing. What I find most exciting as a mobile trend are the growing number of local solutions being built in the developing world – local app developers and techies and non-profits building solutions to their own problems, not importing them from outside. For too long technologies have been designed, developed and owned by outside (often larger) international organisations, who fly in with them and try to get adoption. This is a perfect reflection of the top-down nature of traditional development. As more and more people in-country become skilled in app and tech development, less and less will need to come from the outside, and for me that’s a good thing.

E4C: Now that mobile technology has caught on as a tool for global development (thanks in part to your own work), what reservations do you have about its potential to improve lives in developing countries?

KB: The greatest tendency in the ICT4D field (as we like to call it) is to get carried away with the technology, and take our eyes off the people and the actual problem. We quickly get caught up in the potential of drones, 3D printers, the Internet-of-Things and iPad Pros and forget that there are still many problems out there that can be better solved with things like a simple text message. The biggest danger we have in development is that we’ll fail to solve many problems because we’re too fixated on being cool and innovative – things which often fail because the technologies we see as being cool and innovative often fail in the environments where we work.

E4C: The publisher of your new book writes that it will be an “invaluable resource for… insight into what really works – and what doesn’t.” Do you have an example of a thing that works and a thing that doesn’t?

KB: The ‘things that work and things that don’t’ refers more to the process than the end result. So there are no ‘failed’ projects in the book. What’s crucial is to learn about the many barriers and obstacles and u-turns that innovators face and make on a daily basis, highlighting failure as part of the process, not the end result. So for anyone who wants to get the whole story behind social innovation – not just huge impact figures and stories of amazing people who have done amazing things, but the heartache and frustrations and struggle that many faced to get there – then this book is for you. Social innovation laid bare, if you like.

E4C: You’ve thought a lot about innovation within tight resource constraints. Do you have an example of how the lack of resources led to a good idea?

KB: I think you can find these all over the developing world. Mobile banking would be a great example, in Kenya, where the lack of the bricks and mortar of the more traditional banking sector approach meant that people have turned to their phones to access financial services. We have less need to do that – we have cash machines and banks and online banking easily available to us – so our incentives to disrupt or leapfrog are less. Across Africa, mobile phones are being used in healthcare delivery for similar reasons – the lack of health infrastructure (and trained doctors and nurses) means that people are having to get creative, and the mobile phone happens to be the best device to use if you want to establish a direct connection between a patient and doctor, or a medical service.

E4C: A theme in the introduction to your book, The Rise of the Reluctant Innovator, is the folly of trying to solve problems in other countries without putting in time living in that country. Do you have an example of that at work?

KB: I think the best example I could share would be my own work with FrontlineSMS (a text messaging platform I developed in 2005 to help grassroots NGOs use SMS to increase the impact and reach of their work). I’d already spent over a decade at that point working across Africa, not on technology projects but trying to understand what life was like for the people I was hoping to help. So I had effectively spent a decade travelling and listening, not looking to solve anything. I had also studied Social Anthropology at Sussex, so was very fixed on anthropological approaches to development – observing, trying not to impact my environment as I learnt, and so on. So, when I came up with the idea for FrontlineSMS at the start of 2005, I knew exactly what the platform needed to do, and how, for grassroots NGOs because I had a considerable amount of experience working with them at that point. Without that insight I’d likely not have built the kind of appropriate solution they needed. Studying appropriate technology, and Schumacher’s thinking, at Sussex also helped me ensure I built a tool that local organisations could take, own, run and support on their own. I still, ten years on, believe this is the best approach in ICT4D yet so many technology projects continue to built inappropriate (complex, expensive, top-down) solutions, many of which continue to fail.