The American Society of Mechanical Engineers’ Journal of Medical Devices made a special issue available free and open to the public until mid-April 2020. Medical Devices for Economically Disadvantaged People and Populations contains research on technologies designed to serve emerging markets and underserved communities in any country worldwide. In an introductory essay, Boris Rubinsky, a mechanical engineer at the University of California, Berkeley, pulls on two threads that will interest medical device developers: targets for future design and new technologies that hold promise for positive impact among the world’s poorest populations. Dr. Rubinsky captures the context of the problem and proposes that engineers have a larger role to play in the solution than what they have so far taken on.

“The increasing cost of medical devices is disproportionately affecting economically disadvantaged people around the world. As of 2017, over half of the world population is too poor to access health services and related expenses are impoverishing hundreds of millions. Among those that can afford healthcare, nearly a billion people spend 10% or more of their household income on health expenses for themselves or a family member. For almost 100 million of these, the expenses are high enough to push them into extreme poverty, forcing them to survive on the equivalent of just $1.90 or less a day.

“Many of the findings and discussions relevant to medical devices in ESDPs [economically and sociologically disadvantaged populations] are published outside the engineering community. However, it is the opinion of these editors that a concerted engineering effort is essential to addressing and overcoming the current challenges being faced.”

Targets for new design

Research into new medical devices that can have an impact in the world’s underserved communities could start with insight into which technologies are most beneficial now, and where are the shortcomings. For the first, the World Health Organization maintains a list, as Dr. Rubinsky mentions: WHO’s list of priority medical devices.

And the second is understandably beyond the scope of an introductory essay, but Dr. Rubinsky ventures to start a list that could fill volumes. The list’s opening entry is medical imaging technology: Needed in underserved medical centers, expensive, requires specialized knowledge to operate and maintain, and popular solutions amount to a shocking waste of resources. Two such measures are the purchase of low-cost and low-quality devices that do not last, and donations of technologies from medical centers in more affluent regions.

Donations have been a temporary measure to try to paper over a problem, but they have become the cliched example of wasted effort in global development strategies. Examples abound of donated equipment that has stopped working for lack of routine maintenance because people on the receiving end are not trained. And donations can break because they are not designed for physical environments and intermittent power supplies at the medical centers where they are shipped. Donations are a poor substitute for affordable devices designed for and with professionals in the areas where they operate.

Promising new technologies

Dr. Rubinsky places the smart phone at the top of his list of promising new technologies that could be leveraged and improved as medical devices. With peripheral add-ons and apps, phones are already in use in medicine. Examples include ultrasound, microscopy, microfluidics and other diagnostics, and the rise of articifical intelligencec and diagnostic algorithms may be key in imporoving the phone’s versatility as a medical device in the future.

Besides the phone, articles in the special edition feature other notable technologies.

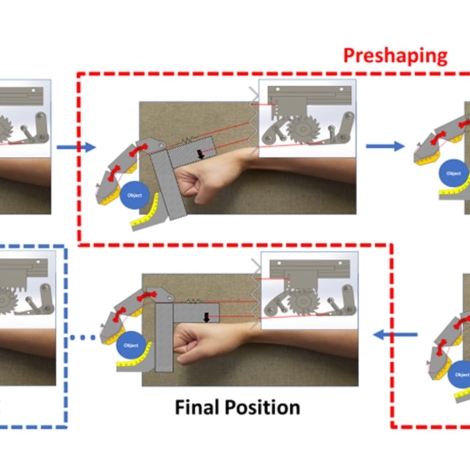

“This SI showcases work developing low-cost arm rehabilitation systems, 3D-printed hand prostheses, and improved, frugal liners for lower leg prostheses. Other articles exhibit novel intrauterine tamponade designs for treating postpartum hemorrhage, low-cost oxygen blenders for infant bubble continuous positive airway pressure circuits, and task-shifting devices for enabling the insertion of subcutaneous contraceptive implants by less skilled caregivers. The issue includes manuscripts describing the development of reusable core needle biopsy devices, low-cost electrosurgical units, and inexpensive gene sensors for label-free cDNA detection. A two part series of review articles examine the applications of cryobiology in both cryogenic preservation of living tissues and cryosurgery in ESDPs.”

See Dr. Rubinsky’s essay and all of the research in this special edition of the journal at the link below.