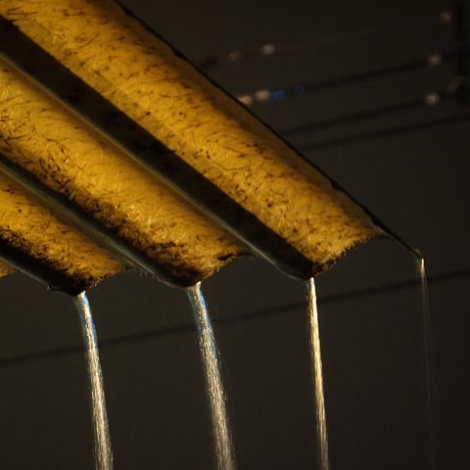

Rain pours from a rooftop in the Ecuadoran coastal city of Guayaquil. A new study links heavy rains that follow dry weather to a 36 percent uptick in diarrhea cases.

Diarrhea rates may be tied to rainfall patterns in developing countries. In the low-lying villages of the coastal province of Esmeraldas in northwestern Ecuador human waste accumulates on the ground and in unsealed latrines when the weather is dry. Then the rain comes, flushes the waste and muddy pockets of incubating pathogens into rivers and watering holes. Two weeks later, diarrhea rates rise by 39 percent, a new study published in the American Journal of Epidemiology has found.

That’s the best explanation for the uptick in diarrhea cases, according to Karen Levy, who led the research at Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health. Levy and her team studied 19 villages in the region and found that diarrhea rates increased and decreased with rainfall patterns. They also found that water treatment, but not sanitation, can help. The results suggest how to predict changes in disease rates before they happen and mitigate the damage. But they also call attention to one of the most vexing problems with sanitation and water treatment: non-compliance.

Weather, diarrhea and water treatment

The researchers found that heavy rain can foretell both an increase and a decrease in diarrhea rates. Diarrhea decreases by 26 percent when the downpour follows weeks of light showers, the researchers found. The reason, they suppose, may be that human waste cannot accumulate when light rains constantly wash it away.

The surge in diarrhea rates disappears when at least 71 percent of the community treats its water. The most popular kinds of water treatment in the region are boiling and chlorination, Levy says. But interestingly, sanitation did not afford the same protection, at least according to this study. There may be a few explanations for the finding.

“It’s possible that our measures of sanitation don’t accurately represent protection, or that none of the communities in our study had high enough latrine coverage to make enough of a difference. On average, only 46 percent of households reported using a latrine,” Levy told E4C by email.

“In other words,” Levy says, “having a toilet doesn’t necessarily guarantee proper waste disposal, and if you use a toilet but your neighbor doesn’t, your family will still be exposed to fecal contamination. Also, an improperly built latrine might end up serving as a point source of fecal material into the community in the face of heavy rainfall.”

Treatment, sanitation and hygiene programs work

Dirty water and diarrhea are everyday facts of life worldwide. As many as 1.2 billion people, or 18 percent of the global population, may drink contaminated water, one study has found.

Water treatment is an obvious solution, and the World Health Organization offers a detailed guide for choosing the best intervention for each situation.

Levy’s research notwithstanding, sanitation and hygiene can also prevent diarrhea and other illness. An analysis that pooled the results of 46 studies on sanitation, hygiene and water treatment programs in developing countries found that those measures can reduce diarrhea and other other illness by 25 to 37 percent. Sanitation in particular reduced the risk of illness by 32 percent, according to the meta-analysis published in 2005 in The Lancet.

But use it or lose the benefit

The issue that many of these studies hide, however, is that people don’t always use the latrines or the water filters. Or they don’t use them correctly.

“Compliance and uptake is a big issue in efforts to improve water quality, and ultimately much harder than providing good treatment technology. We need more research into what motivates people to treat their water, and what the barriers are to adopting these technologies,” Levy says.

“It takes a village” really is an apt cliché when applied to cleaning up the water. Even just a few people can cancel the health benefits of a whole community when they don’t treat their water or when they defecate in the open or simply use their chlorinators or latrines in the wrong ways. If just one household or one work site serves untreated water to guests or employees then many people can get sick. When 90 percent or less of a community fails to adhere to clean water programs, the benefits can drop by up to 96 percent, according to a study by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine published in 2012.

Questions for future studies

Public education may be the best long-term solution for enticing people to use water-improving technologies. But design can also play a part. Design that weaves itself more intuitively into people’s daily habits, or that makes an intervention easy to use and hard to botch, may improve uptake. Maybe those designs are already here. Boiling, for example, may be one of the cooking chores in many kitchens now, and it could be extended to drinking water. Or maybe new designs will come with more targeted research and creativity, or from inventors in each of the vulnerable communities themselves.

Levy’s research will hew more closely to the life cycles and impact of the different microbes that cause diarrhea.

“Each organism has a different life history and survival time in the environment, so environmental cues affect them differently. When you just look at “diarrhea” you clump all these disease agents together, and create a lot of noise in the analysis, especially when considering seasonality. We know that viruses tend to peak in cooler months, and bacteria tend to peak in warmer months, so my group is carrying out investigations about how these different organisms respond differently to climatic drivers,” Levy says.