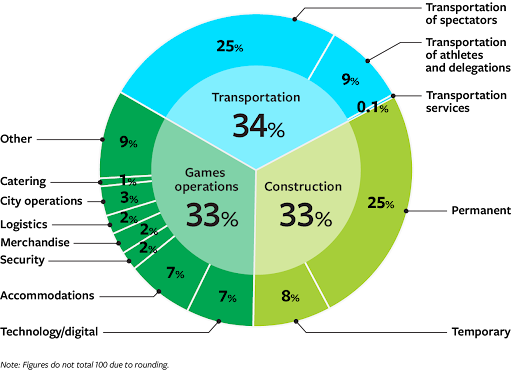

One of the least discussed traditions of the Olympics is the environmental degradation left behind when the crowds leave. The Olympics average an output of 3.5 million tons of CO2, and each event has damaged the natural world in a bid to accommodate athletes and fans.

The 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics is a notorious example of high-cost infrastructure construction marred by environmental damage and corruption. Massive construction projects led to illegal dumping, polluted rivers and drinking water, and landslides that damaged homes and destroyed animal habitats.

Four years later in PyeongChang, the 2018 Winter Olympics oversaw the falling of thousands of trees, displacing animals to clear ski slopes. The sacred site Mount Gariwang, was determined by the International Ski Federation to be the only place in Pyeongchang suitable for the Alpine courses, resulting in the removal of 58,000 trees. And those examples are just a fraction of the ways the Olympics and other large gatherings take their toll.

Three main sources of Carbon impact according to an analysis by MIT Sloan Management Review. Image used with permission.

The IOC’s Sustainability Strategy

The Olympics took a turn toward sustainability in 2020. As a part of the Olympic Agenda 2020, 40 recommendations were made to shape the future of the Olympic games, in which Recommendations 4 and 5 were directly aligned to sustainability.

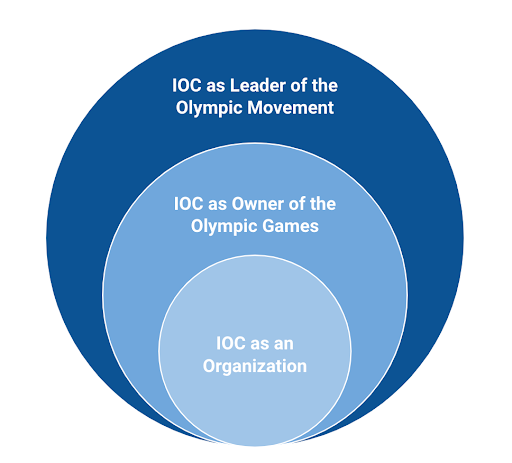

Recommendation 4, “Include sustainability in all aspects of the Olympic Games”, describes the International Olympics Committee’s (IOC’s) role in integrating sustainability into the planning, staging, and future of the Olympics. The Committee also recognizes that host cities will be largely responsible for carrying out this recommendation.

Recommendation 5, “Include sustainability within the Olympic Movement’s daily operations,” defines three key elements: develop the IOC’s corporate sustainability program, share best practices to further the Olympic Movement, and leverage partnerships to advocate for the role sports has in global sustainability discussions (Olympic Agenda 2020). With these recommendations, Olympic organizers developed a long-term approach with targeted objectives within three spheres of responsibility illustrated below. Although initial steps to formalize procedures and practices have been taken, the critical question remains how effectively these objectives are applied in practice.

The IOC Sustainability Strategy Framework. Image: Created by the author, based on data from the IOC.

How Sustainable Were the 2024 Olympics?

The 2024 Paris Olympics set out to be more sustainable than previous games and learn from past Olympic environmental impacts. This year’s Olympic organizers cut emissions in half compared to previous summer games. Rather than mounting new construction projects, 95% of the venues were existing or temporary structures. There was some new infrastructure built for the 2024 Games, such as the Paris Aquatic Center and the Olympic Village. And organizers encouraged spectators and teams to use public transport. In a notable example, four teams from the Netherlands, Britain, Belgium, and Switzerland traveled by train to reduce airplane emissions.

Additionally, to reduce energy consumption, Olympic organizers leveraged solar panels and prioritized drawing energy from the French power grid based on nuclear power, and renewable power from the French national utility company, EDF.

Sustainable products also made an appearance in this year’s games. One set of eye catchers is the unique Olympic medals crafted from the metal preserved from Eiffel Tower renovations, or repurposed from Monnaie de Paris, the French government coin producer. Furthermore, approximately 30 parade boats were electrically propelled as they traveled down the Seine River during the opening ceremony.

Although Paris has made strides in prioritizing sustainability for the Olympics, considerable work remains to ensure the commitment continues.

About the Author

Bethlehem Mersha is a 2024 Engineering for Change Fellow and an engineer with a B.S. in Mechanical Engineering and an M.S. in Technology Innovation & Entrepreneurial Engineering. With experience in manufacturing and design, she works as a cnsultant in the energy industry. As an E4C Fellow, Bethlehem is focused on assessing the impact of the ASME ISHOW program. She is passionate about driving sustainable change and making a positive impact through her work.