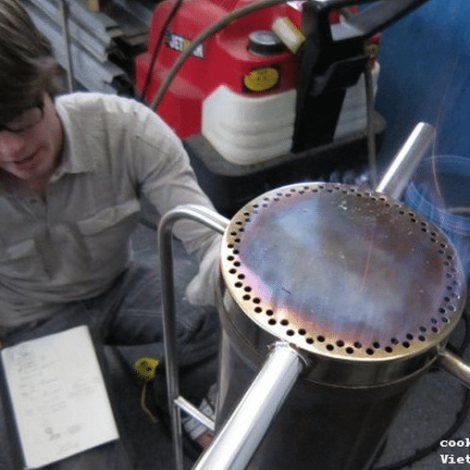

I spent the year developing a better way to fire bricks in Vietnam. It all started with an idea to gasify rice husks to cook meals in rural Nicaragua. My team developed this technology as a senior project in mechanical engineering at the Georgia Institute of Technology. We devised a way to use the thermochemical process of gasification to turn the husks into a clean cooking heat.

We tested our ideas outdoors on campus every week and kept a little blog about our project. Something strange started to happen: as people spread the word about our project, we got calls from around the world of people interested in using the technology. One of the folks that I got into contact with was a consultant in Vietnam. As the semester progressed, I realized that I wanted to continue exploring this strange fire-making technology and so I set off to Vietnam to volunteer as a fire maker.

I arrived in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, and began to chase down the source of any smoke I saw the distance. Smoke is a problem to an engineer: it signals incomplete combustion. Following the smoke led me to charcoal makers, women frying bananas, trash incinerators and, eventually, brick kilns.

Making charcoal briquettes in rural Vietnam. Photo courtesy of Marc Pare

Making charcoal briquettes in rural Vietnam. Photo courtesy of Marc Pare

Kilns stuck in time

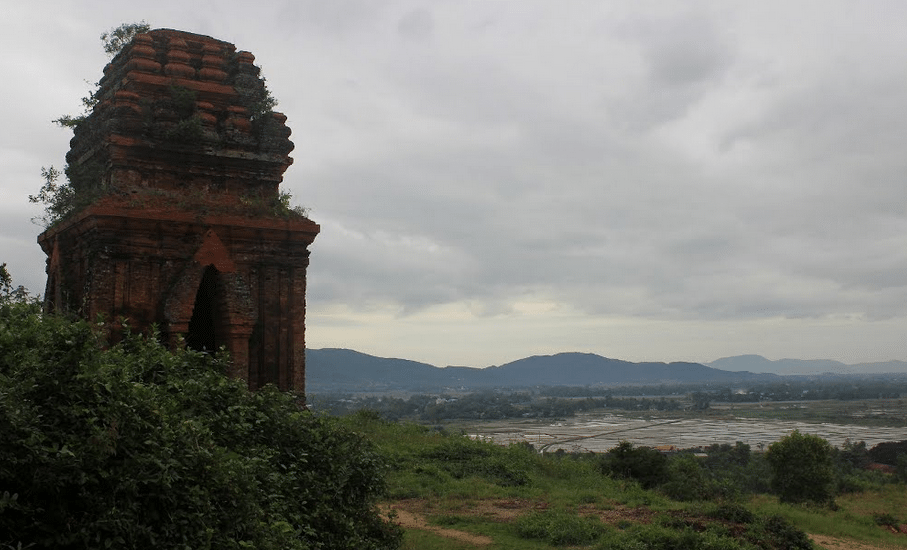

Brick making is an ancient industry. The techniques used in many developing countries go back thousands of years. In Vietnam, you can find brick towers built by the Champa civilization, which ruled parts of the country from the 7th to the 19th centuries.

Their ancient technology is almost identical to the process that you find in Vietnam’s brick-making regions today. Unfortunately, as demand for construction material has grown, traditional techniques can’t keep up. That is, their environmental impact, while negligible when demand for bricks was low, has become an extraordinary air pollution problem.

Photo courtesy of Marc Pare

Down the rabbit hole we go

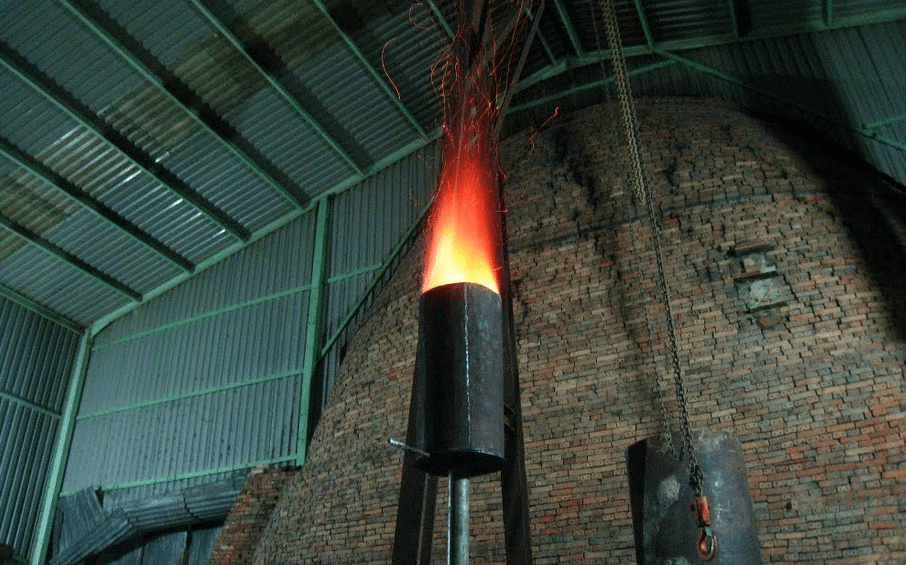

It was about eight months ago that I first sketched a gasifier and a brick kiln together. And, despite my fumbling and inexperience, the project has moved further than I had ever thought it would. Two months ago we lit our first rice husk gas flare. Not only that, but the technology has hit all of the specifications that we required: cost, size, operating characteristics (it had to be a simple for kiln operators to learn to use).

You can find a description of the specifics of our project on our website and on the recent Dell Social Innovation Challenge page. It has been an interesting journey, to say the least. I encourage anyone with the inclination to make a difference with technology to follow your nose on your crazy ideas. With that in mind, here are a few things that worked for me. I hope they will show you that a lot more than you might think is possible.

Rice husk is used here to make rice paper. Photo courtesy of Marc Pare

Don’t get married to a particular application

It was when I opened my mind to gasification as more than just a cooking technology that I started to see hundreds of opportunities in Vietnam. That took me away from the one sort of lackluster application I had first experimented with (rice husk for cooking is possible but very difficult to market).

A mountain-top Champa tower in Quy Nhon. Photo courtesy of Marc Pare

Finding a local partner is more important than a clever technology

The dirty secret of applying technology to effect change in the developing world is that it doesn’t exist in isolation; you have to consider a whole range of social cultural and political constraints in the design of even the simplest thing.

One of the ways that you can shortcut this aspect of the design process is to find a supportive and capable local partner organization. My partner in Vietnam is ENERTEAM, an energy and environment consultancy. They are incredible, and very supportive of my work. I know that if I run a design idea by them and they get excited, then it has potential; if it falls flat, then there must be some factors lurking underneath that I didn’t consider. This is pretty cool because you get to incorporate tacit knowledge—that knowledge that people can’t always describe with words—into your design.

The kiln team’s first successful flare. Photo courtesy of Marc Pare

There aren’t many engineers out there

Many of the NGOs that I have met over the last year don’t even consider involving engineers in the design of their projects because they just can’t find them. The result, to an engineer, is boring and unambitious applications of technology to development.

The other side is important to consider as well: If you’re an engineer, you’ve got to get out there if you really want to make a difference. You’re up against a nearly incomprehensible web of anthropological and sociological constraints; you have to get feedback early and often in your design process. The American Society of Mechanical Engineers calls this attitude “let’s go see” in the Unwritten Laws of Engineering.

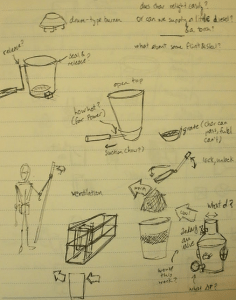

An early sketch of the gasifier kiln. Image courtesy of Marc Pare

Don’t do your research on Google

Don’t do your research on Google

You are looking for two things in your research: practical information and rare information. The Internet is great for a lot of things but most of the technical information that you find online these days tends to be biased towards the new and shiny. An Arduino microcontroller won’t really help you very much in the field.

I’ve found that technical material written around the 1940s ’60s and ’80s for gasification is the most useful. At that time, many cars and trucks used gasifiers as an alternate fuel source. my technical Bible is a 1984 thesis written at UC Davis. It’s a difficult text to find, I ordered the last copy available from online used book sellers. Something else to consider, the stuff that bubbles to the top of Google results is the stuff that everybody else is reading. Unless you’re freakishly creative, you’ll just end up with same dozen ideas that everybody else has. Fortunately, there are remedies to this. Use the library, find the graybeards in your application area and ask them what to read. The point isn’t to look for answers (which is usually what you’re doing on Google) but to equip yourself with design tools.

In closing, be bold

If there’s one thing to take away from this experience, it’s that engineers will have a lot to say about where our world is headed. Be bold and build things! Oh, and if you’ve got a project on Dell’s contest site, let us know in the comments. I would love to see what others are working on.