Passengers ride on the roofs of overcrowded train cars in Mumbai. Photo: Anand Balasubramaniam (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Nearly 3000 train services carry 8 million passengers daily through Mumbai, India’s financial capital. Suburban trains are chronically overcrowded, especially during peak hours. People travel in dense crush loads of 16 passengers per square meter, among the densest conditions in the world. Images of scores of commuters hanging onto the doors of overflowing compartments have become iconic.

Until now, the steps taken to ease congestion have focused on increasing the trains’ capacity. Big ticket, multi-million dollar endeavors, such as the Mumbai Urban Transport Projects funded by the World Bank, have launched and then failed to meet their targets. As the Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) of the World Bank noted “better services increased demand more than had been expected.” Consistent with Lewis Mumford’s classic observation, adding capacity to deal with congestion was like loosening one’s belt to cure obesity. Clearly, in India’s context of increasing population growth, a singular focus on boosting passenger capacity is unwise, especially in light of the fact that the suburban railway system currently operates at a major loss.

Moving non-motorized transport from the fringes to the center stage

While India’s social commitment to mass transit is admirable, an integrated approach would be much more preferable, wherein non-motorized transport infrastructure took the load off the trains by weaning short-distance travelers. About one-fifth of commuters use suburban trains to travel less than 10 kilometers (6.2 miles). Such short distances could be easily covered by bicycle or even on foot if safe paths were available. And non-motorized transport paths would be much more cost-effective in decongesting suburban trains than increasing capacity. Simultaneously, non-motorized transport could provide comfortable and flexible last-mile connectivity to the suburban railway stations, while at present millions of people must access these by bus.

Poor infrastructure makes Mumbai train stations dangerous for pedestrians. Photo Allison Giguere (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

In Indian cities, the share of cycling and walking is enviable, ranging from 58 percent to 30 percent. Mumbai, in particular, is ideal for cycling. It has high densities, mixed uses, a linear geography, flat terrain, and mild weather with nine rain-free months per year.

Still, non-motorized transport is seen as a poor cousin of motorized vehicles; both the Indian government and international funding agencies seem to share the view. While the Mumbai Urban Transport Projects made small provisions for pedestrian crossing facilities, most were cancelled due to reduced funding. Similarly, one of India’s largest urban infrastructure projects, the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission did not encompass a single project catering to walking or cycling.

In Kolkata, authorities went as far as attempting to outright ban or covertly squeeze cyclists off the roads by framing them as a “traffic impediment.” In Mumbai, ‘skywalks’ proved a misguided attempt to cater to pedestrians’ needs in the vicinity of train stations. Initiated with much fanfare, most skywalks ended up poorly patronized. This should have been unsurprising given that pedestrians were forced to climb up stairs while motorized traffic flowed below. The project was eventually aborted.

Skywalks like this one in Thane, Mumbai, have only increased the chaos on the streets. Photo: WRI Center for Sustainable Cities (CC BY-NC 2.0)

India’s (and Mumbai’s) persisting urban transport problems are often attributed to a lack of institutional capacity, clarity, and ownership. Urban transport falls under the purview of multiple agencies under the central, state, and local government umbrellas but outside the purview of the railway administration. Meanwhile, state governments oversee local land use. As a result,transport policies are neither nuanced nor integrated.

Cyclists and pedstrians share Mumbai’s overcrowded roads with motorized vehicles. Photo: Adam Cohn (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

This bleak picture notwithstanding, positive change must start somewhere. In fact promoting walking and cycling have been proved to be the most cost-effective measures in reducing congestion. Bike sharing initiatives in China led to improvement in traffic conditions in 80 percent of China’s 100 biggest cities, and costs related to traffic congestion fell by $ 2.6 billion. Though data is not available for the city of Mumbai, study conducted for the city of Beijing to see how bicycle could decongest the overcrowded Beijing Metro found that 13 percent of current metro riders and 10 percent of bus riders could be easily shifted to bicycling.

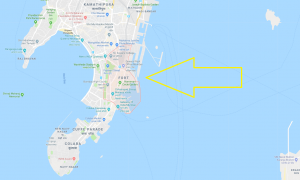

In Mumbai, a highly visible pilot could be the conversion of the central Colaba Fort area into a pedestrian and bicycle-friendly space. More than money, the implementation of such a pilot would require a political champion, Mumbai’s very own Bicycle Mayor who could propel a much-needed transformation in mindset.

In Mumbai, a highly visible pilot could be the conversion of the central Colaba Fort area into a pedestrian and bicycle-friendly space. More than money, the implementation of such a pilot would require a political champion, Mumbai’s very own Bicycle Mayor who could propel a much-needed transformation in mindset.

About the Authors

Vineet Abhishek is a civil servant working with the Indian Railways, currently posted at Mumbai, Western Railway.

Dorina Pojani is a Contributing Editor at E4C and Senior Lecturer in urban planning at the University of Queensland, Australia.