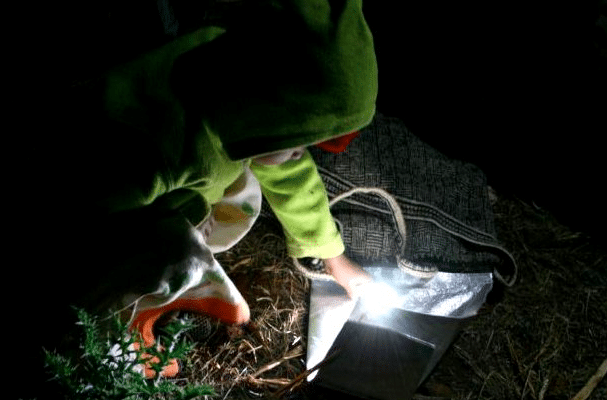

The lantern is a prototype developed in Brazil that incorporates the Portable Light Project’s solar textiles into a locally-made design. Image courtesy of the Luz Portatil Brasil team

Like most good ideas, making solar power wearable is a solution that seems obvious in hindsight. With flexible thin-film solar cells and batteries integrated into their textiles, people with mobile day jobs charge their phones and light their off-grid homes at night.

The Portable Light Project had this good idea and the program has distributed customizable kits to families and professionals in nearly a dozen countries. Off-grid communities integrate the kit’s unique solar technology into their own local materials and fabrication techniques. The result is low-cost, clean power with a familiar feel.

“We’ve produced a simple solar textile kit which is adaptable,” Sheila Kennedy, who heads the project as a senior principal at the Boston-based firm Kennedy & Violich Architecture, Ltd., told E4C. That adaptability, Kennedy says, has been valuable.

“There is so much over-specified stuff out there— do we really need another cheap plastic gizmo? Instead, we need a system which is enduring, resilient and versatile.”

The specs

For $18, the kits include an LED lantern, a rechargeable 3.7-volt lithium-ion battery, and a three-watt copper indium gallium diselenide thin-film panel with a relatively high current of one ampere, a circuit board or control tray with USB ports for charging devices.

High current was important in the design, Kennedy says, because people rely heavily on solar power in the off-grid communities where her team works. With their generator, the battery charges in five to six hours of sunlight.

“I do believe that we have the smallest-footprint, fastest charging flexible photovoltaic system in the world,” Kennedy says.

Solar’s hidden pollution problem

The kit’s light carbon footprint is one of its selling points. Solar panel manufacture pollutes, of course, and it could take about two years of operation before a crystalline silicon panel offsets the pollution created when it was built. Studies show (pdf) that thin-film panel manufacture may be about half as dirty and take only about one year to break even.

Also, as the technology has improved, the kits use fewer panels.

“I have seen efficiency go up dramatically. When we started working in 2005 and 2006, we had to have two panels. Now we can do it with one panel, which has halved our costs,” Kennedy says.

The project further reduces its manufacturing carbon footprint with flat-to-form fabrication. The process takes a three-dimensional object – the lantern – and then creates a flat, two-dimensional template for folding. Local manufacturers can then use the template to cut the shape of their preferred textile and fold it into the lantern.

“The flat-to-form idea is very simple, but it represents a big departure from singular, hard designed objects, which is what so much of typical industrial design is—all that plastic and glass, all that embodied energy,” Kennedy says.

Beekeepers and turtle patrols

Portable solar has manifested in creative designs in a handful of countries in Latin America and Africa. Solar textiles serve beekeepers and women’s cooperatives in Brazilian Amazon river communities. Students in Rio de Janeiro helped design two fold-to-form lantern templates that attach to bags and boats and are used by nearly 500 families living off the grid.

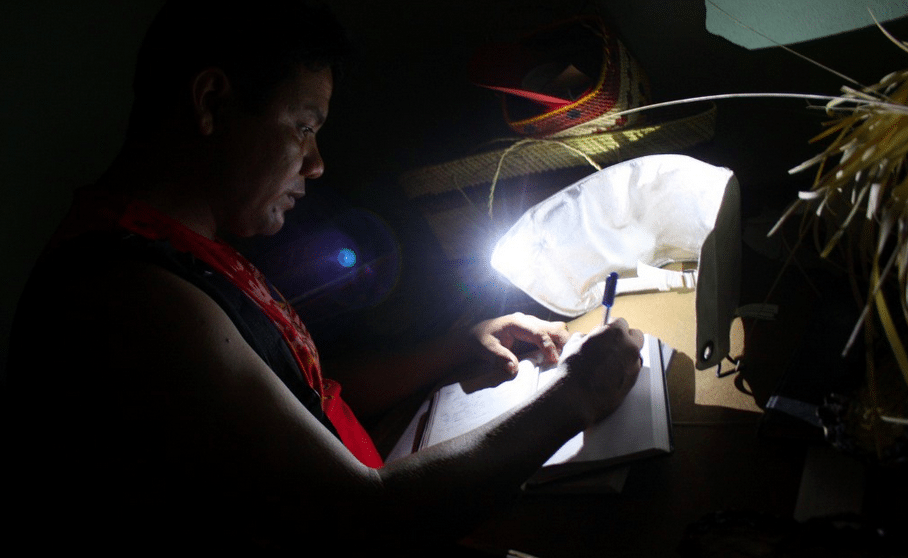

Nicaraguan rangers working with the conservation organization Paso Pacifico hook a solar textile and LED lantern onto their bags by day, and remove it to light their homes at night. The lantern can switch to red light for nighttime beach patrols that protect sea turtles and their eggs from poachers.

In Haiti, traveling midwives working with the organization Maison de Naissance in Haiti power lights and charge medical devices while visiting their patients. The project may also be poised to make new inroads in Haiti soon.

Soft infrastructure

Solar textiles may something more than just a one-off solution. They could be front-runners in an emerging field of materials that perform services. As such, the textiles represent “soft infrastructure” that could replace the machines of traditional infrastructure, Kennedy says. “Those materials are creating a different definition of infrastructure. We used to think of infrastructure as a technology, or a physical object, but now materials can actually produce infrastructural effects – creating energy, creating light and storing power,” Kennedy said in an interview with the Global Journal.

It’s interesting to hear Kennedy speak about the significance of soft infrastructure and what it can mean for future trends in development. We’ve shared her thoughts in a question-and-answer feature here.