A workshop was held in Kampala, Uganda to announce a new fund for energy access entrepreneurs. Approximately 50 excited Ugandan entrepreneurs turned up. The consultants in charge of administering this fund described complex rules, unfavorable lending schemes, and inappropriate financing for early stage local companies. The disappointment in the room was paramount; frustrated, an official from the Ministry of Energy shouted at the consultants, “why are you giving hope to these people that they will get funding and waste their time, when you will just award foreign companies?” Unsurprisingly, months later, foreign PAYGO companies were awarded. This story is part of the lingering destruction of colonialism, and the white supremacist belief that people of color are not capable of leading themselves; the belief that gender equality, good governance, and economic advancement can only occur through outsiders creating and implementing solutions for people of developing nations. Let’s not pretend this is a level playing field and address the elephant in the room – race also absolutely matters when achieving universal energy access. To ignore this important conversation does a disservice to the Sustainable Development Goals.

Let’s not pretend this is a level playing field and address the elephant in the room – race also absolutely matters when achieving universal energy access.

During the colonial development of southern nations, electricity was delivered first to white settlements. This was no coincidence; by denying electricity to the underprivileged masses, power (literally and figuratively) and opportunity was also systematically denied. The entire electrification planning and grid infrastructure created in southern countries over the past 150 years has been baked into colonialist and white supremacist politics, shaping decisions on who should benefit or be excluded, long after independence. Yet this discourse is never brought up when discussing modern day electrification. The past, however, impacts the future. One such horror show, Buchanan Renewables Energy, is a modern day example of how foreign American entrepreneurs exploited not only the Liberian poor, but devastated natural resources. They utilized millions of dollars from OPIC to support their corporate greed, creating serious human rights, environmental, labor, and sexual abuse violations and treated locals as dispensable workers. Worse, the founders faced no consequences for their actions and have gone on to start new venture backed companies. There was a reason as to why the film Black Panther was met with such enthusiasm in Africa. Never before were Africans allowed to dream that they themselves could create technology to advance their own nation, without any assistance from the outside.

Grid infrastructure created in southern countries over the past 150 years has been baked into colonialist and white supremacist politics, shaping decisions on who should benefit or be excluded, long after independence.

Is the sector increasingly looking like a neo-colonial attempt to capitalize the lack of electricity off of the backs of the poor to bring profitable returns to foreign investors? Again, Africa’s resources: this time the sun instead of rubber, is promising wealth outside of the country. East Africa is awash with solar companies accessing cheaper capital overseas, disadvantaging local entrepreneurs who simply cannot access the same on similar terms. When foreign energy companies are awarded with large-scale financing, it’s true that ultimately the consumer will benefit from accessing clean energy, which is the target of the Sustainable Development Goal 7. But what about the country? Does their GDP rise as a result of this new market opportunity? Are thousands of full-time employment jobs being created and is the sector providing a boost to the tax revenue base of the country? In other words, is energy access successfully contributing to Sustainable Development Goals 8, 9, and 10, which are decent work and economic growth, industry, innovation and infrastructure, and reducing inequalities? Anil Gupta, a Professor from the Indian Institute of Management said, “I would not mind involvement of designers from anywhere as long as they come with an open mind, share their learning with/from grassroots learners, and give credit where it is due. The problem arises when some so-called do-gooders raise huge funds, pay fat salaries, and use their partnership with local communities to legitimize their greed.” In the energy access sector, which is occurring?

In the face of adversity, however, is always opportunity. Here are some suggestions for staeholders to improve on racial equity and energy access planning:

- Level the playing field. Ecosystem support services are critical, which includes backing local SME financiers and local intermediaries which need to provide cheaper debt capital in local currencies to local entrepreneurs. Philanthropists can concentrate their donations towards local entrepreneurship readiness programs, such as incubators, accelerators, and women’s empowerment initiatives that strive not just to deliver energy access but focus on human development. For example, Sendea provides necessary growth capital for local small and medium solar enterprises.

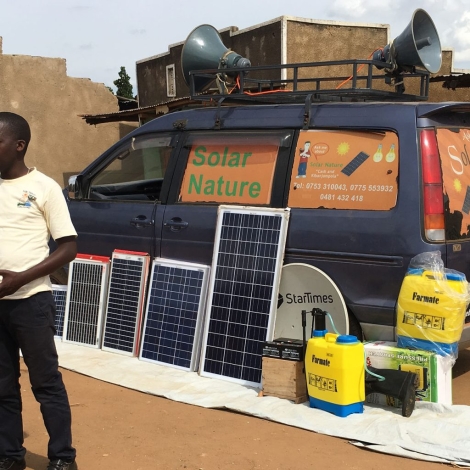

- Community owned renewables are essential to advancing racial equity. Elevate the grassroots and environmental justice leaders in planning. For example, ENVenture solely works with grassroots leaders to create community owned clean energy distribution.

- Partnerships are good, but joint ventures are great. If you are an outsider with a solution, seek out co-owners and implement joint venture models. Partnerships suggest that both have something to gain, but ownership implies long-term sustainability with the locals having a majority stake in the solution. For example, Empower Generation founder Anya Cherneff is an American who co-founded her organization with Sita Adhikari, a Nepali local.

- Diversity matters. Financiers, especially impact investors can contribute by publishing diversity statistics. What percentage of founders being invested in are in men and women of color? What is the make-up of those board seats of foreign energy access companies? After a thorough examination of existing portfolios, opt for strategies to be inclusive of energy entrepreneurs from the global south and/or people of color entrepreneurs in developed countries, especially those with familial ties to countries with energy access problems.

- Reframe the problem. If you are from the developing world, ask yourself – how can I solve the problem of energy access in my country? If you are from the developed world, ask yourself – how can I help support people in developing countries to solve the energy access challenge?

Racism is endemic to global inequality. It is also creating inequality in the energy access sector. In an industry where every customer of energy access service are poor black and brown people, emphasis needs to be redirected towards supporting local people of color energy entrepreneurs creating solutions. The Black Panther dream can become a reality if the colonialist mindset that is plaguing the energy access sector ceases constraining black and brown excellence.

This piece was first published at Sun-Connect and republished here with permission. Read the original: The elephant in the room—an expose on racial equity and energy access.

About the Author

Aneri Pradhan is the Founder and Executive Director of ENVenture, an incubator that empowers rural Ugandan Community Based Organizations to start clean energy ventures.