Editor’s note: Demand: ASME Global Development Review is shuttering after six years of publishing research, in-depth coverage of the most interesting manifestations of design, engineering and social ventures in global development. The biannual magazine was a premier source of global development writing and a sister publication to Engineering for Change. As an homage to Demand and the work of the experts whose voices it disseminated, we are reprinting Demand’s articles on this site.

This case study portrays the Kenya-based sanitation startup Sanivation, detailing its rise from conception up to the start of a shift in direction and scale. When this essay was published, the company was on the verge of a tilt toward greater size and impact. Emily Woods, Sanivation’s co-founder, describes events that occurred since publication following the original text.

Modern sewage and waste treatment systems were designed to eliminate waste. With a global population set to top 9 billion in 2050, this approach is untenable if the hope is for everyone to live healthily and resourcefully, the Toilet Board Coalition argues. The global network of sanitation champions wants to see recycling and reuse of biological waste become mainstream, and it’s working with entrepreneurs and municipalities to prove that there are numerous ways this can be done at scale.

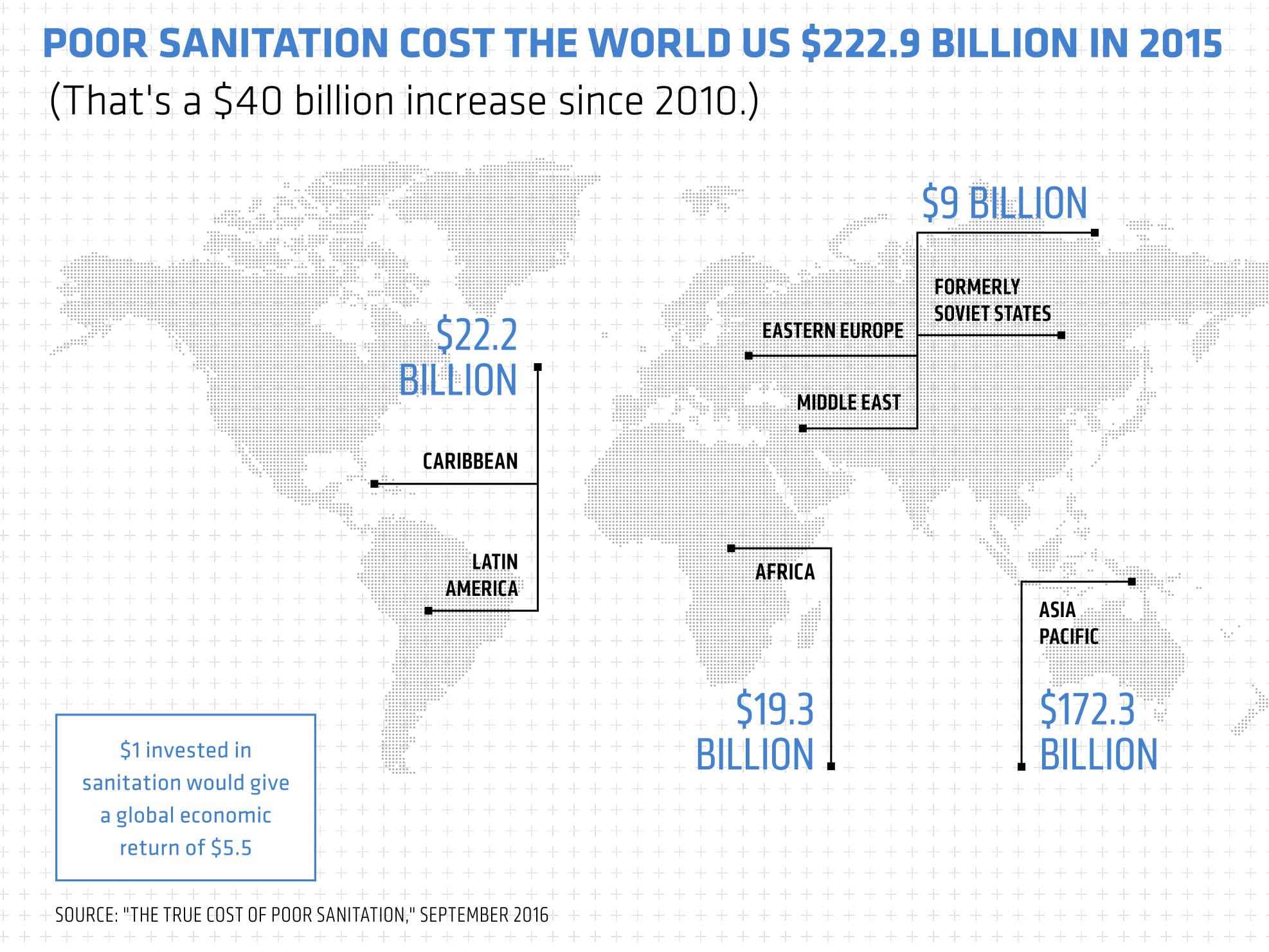

The world has a major problem with waste. Specifically, human waste. Of the 7.6 billion people on the planet, more than 2 billion people don’t have a toilet in their homes, and more than 890 million of them still practice open defecation. That isn’t just a sanitation issue at that scale. It has economic, health and safety impacts as well. Poor sanitation costs the world $223 billion annually, while sanitation-related illnesses are one of the leading causes of child death.

Catherine Berner has intimate knowledge of this problem. “Any decent human being sees that as a problem that needs to be solved,” she says.

An environmental engineer by training, Berner is trying to do just that. She is the manager of product at Sanivation, a sanitation social enterprise based in Naivasha, Kenya that collects “toilet resources,” or human waste, and converts them to fuel-charcoal, specifically. Berner has been with Sanivation since 2015 and supports the design, building, and implementation of Sanivation’s waste treatment facilities; manages partnerships; and conducts market analysis for fuel products.

See Sanivation’s container-based waste collection service in E4C’s Solutions Library

Sanivation started in 2011 with an original goal of addressing that “two billion without a toilet” number by selling toilets and a waste collection “subscription” service to low income urban households. More recently, the company has been working with government agencies and NGOs to support its scalability. In its home city of Naivasha, for example, Sanivation is working with Naivasha Water & Sanitation Company (NAIVAWASS), the city’s water service provider, to build a treatment and processing plant to handle waste from the 85 percent of the city’s homes and businesses that aren’t connected to sewer lines.

“We are working with the government to set up the right partnership structure,” Berner says.

NAIVAWASS could apparently use the support: when Sanivation reached out about a partnership, the utility’s waste treatment plant was at 240 percent capacity and was getting backed up with concentrated fecal sludge.

“Folks are willing to pay to have their pit latrines or septic tanks emptied, but there’s not a funding mechanism for treating that waste. So, we are saying that we will treat that fecal sludge and turn it into fuel at no cost to the plant,” Berner adds.

An outdated system

Naivasha’s woefully insufficient capacity to safely handle its biological waste wouldn’t come as a surprise to Sandy Rodger. Rodger is an engineer who used to run factories and supply chains for Unilever and now heads operations at the Toilet Board Coalition, a business-led nonprofit whose mission is “to accelerate business solutions that deliver sanitation at scale by innovating at the social, economic and organizational levels.” He’s seen plenty of examples underserviced and overtaxed waste treatment systems.

“Because I’m an engineer, I believe that if you design a system well, you tend to get good performance on multiple dimensions,” he says. Either you have a well-designed system or you don’t, he adds. “If you do, it tends to work on all levels. But the so-called linear economy-which we’ve [used] since the Industrial Revolution-in which we use things once and throw them away, is just not very well designed.”

Rodger doesn’t fault the original develop ers of such a system. “Nobody had a plan that said, ‘Hey, let’s use all the stuff once and throw it away.’ It just kind of happened that way,” he says. “Because the planet doesn’t send you an invoice when you use some resource and then throw it away, it seems to be cheaper that way.”

Rodger suggests that the cost of operating this way, if it was properly costed, would be very high, however. “If we are going to have nine billion people on the planet living good lives, we have to get used to the idea of using our resources over and over,” he says.

That’s precisely what the organization Rodger is part of now wants to do. The Toilet Board Coalition was founded in 2014 to “accelerate the sanitation economy” and has recruited executives from several multinational corporations, including Unilever and Unilever-owned Domestos, Firmenich, Kimberly-Clark, Lixil, and others, to support the work. By bringing together companies, social investors, sanitation experts, and non-profit organizations, the Toilet Board Coalition aims to develop commercially sustainable and scalable solutions to enable waste systems and markets to be reengineered.

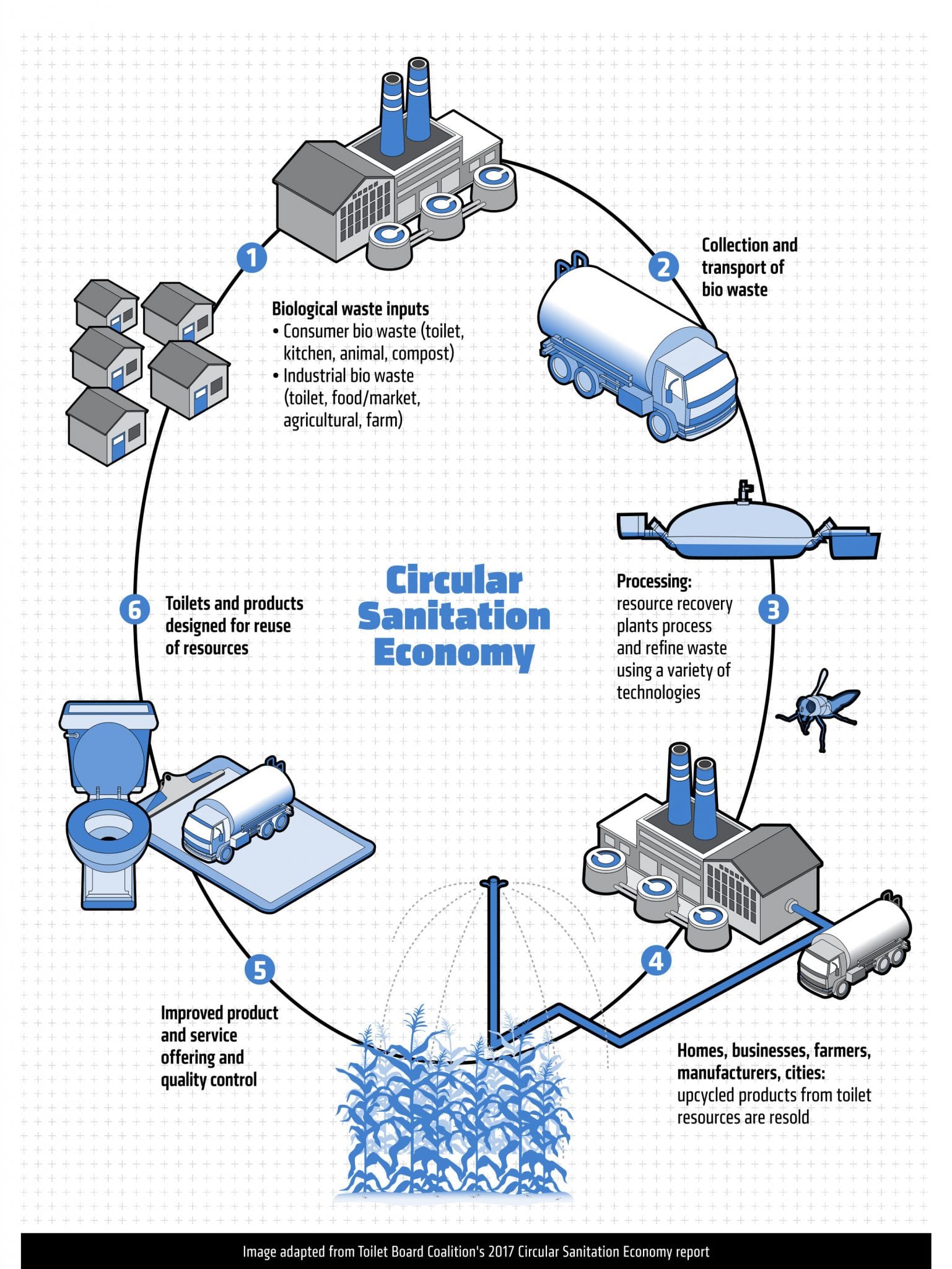

Among the most critical issues the Toilet Board Coalition is committed to is what it calls the “circular sanitation economy,” in which biological waste from food, farms and people, is processed and refined into safe products that can then be sold businesses, cities, and individuals. This is precisely what Sanivation does, and the Coalition believes that such examples of purposeful waste reuse are essential to a healthy global sanitation ecosystem (The other two pillars are the “toilet economy,” in which toilets and toilet products are designed for the reuse of resources; and the “smart sanitation economy,” where sensors and apps are designed and used to capture information about consumer behavior and health.)

The sanitation economy is a challenging sell, however, given humans’ long-engrained ideas about the filth of feces and the urge to eliminate it from our daily lives rather than recycled it back in. Rodger calls this a “cultural hang up” and tries to reframe how people view human waste in more palatable terms: he compares feces to “secondhand tomatoes” leftover in a market, or vegetable scraps that get tossed in the compost bin.

“The way we talk about toilets and sewers, it’s somehow more repulsive to most people than food waste, even though food waste tends to be smellier,” he says. “It’s the same stuff-the tomatoes you eat that then go through your body and down the toilet and those that are wasted from the market.”

Embarrassment and revulsion to waste has influenced the way our waste treatment systems have been designed, however. “A hundred or more years ago, in countries like the U.K. and the U.S., we built sewers to take away the smell [from human waste]” Rodger explains. “And having built those sewers, we have struggled ever since with biological waste. In waste systems, there isn’t actually a consistent way of dealing with compostable waste.”

Out with the old

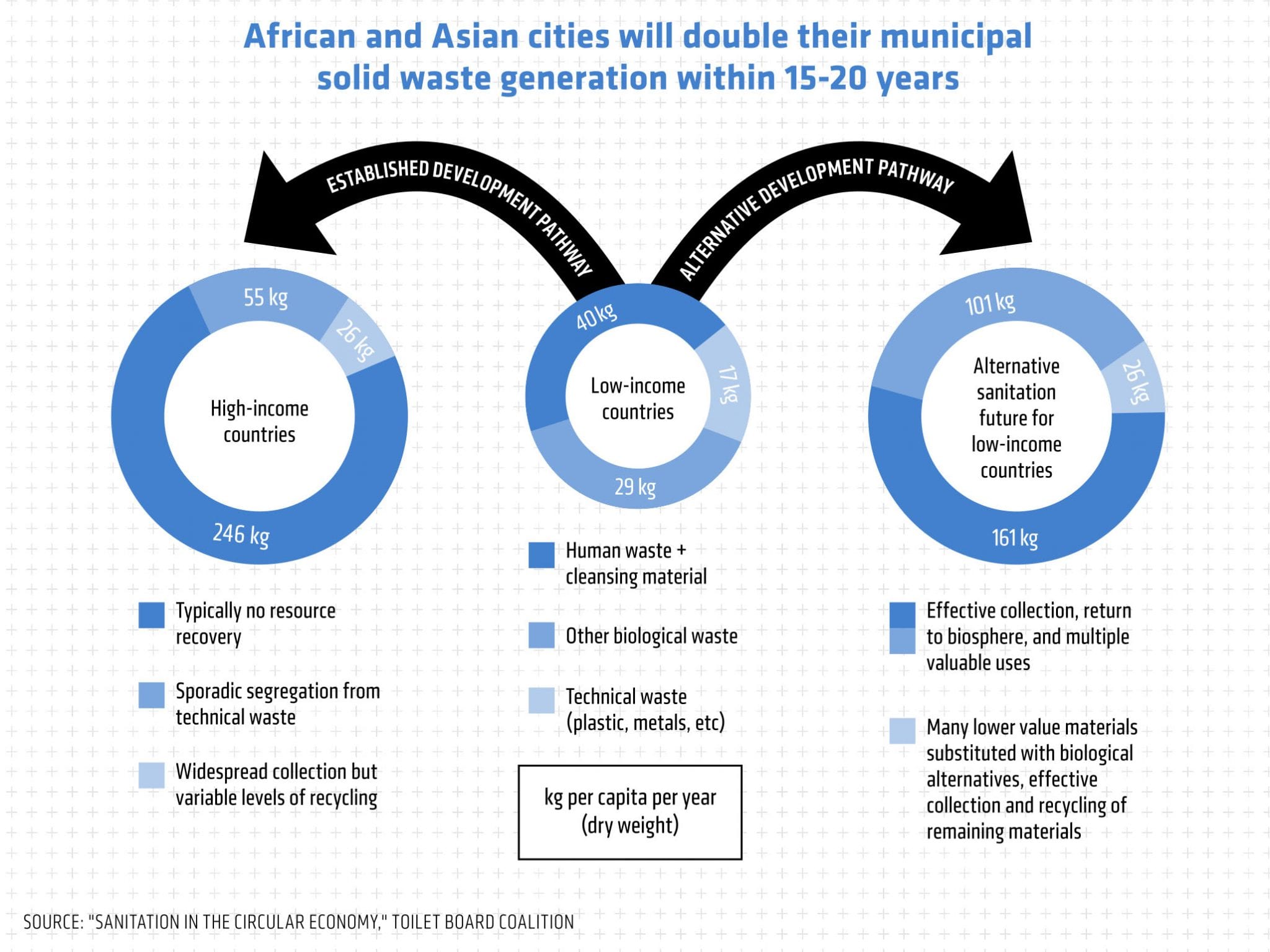

Reforming built systems that have such large and complex infrastructure behind them is incredibly difficult. Rodger has more hope in the near-term for places where sewer infra structure is limited or nonexistent. In many developing countries, for instance, it might be easier to make the case for building what Rodger calls “biological waste systems,” where nutrients from all biological materials, irrespective of source, are brought back to the soil.

The Toilet Board Coalition has witnessed a new crop of entrepreneurs experimenting with this idea in precisely these markets. “They’re not doing it because they have some big idea about a circular economy. They’re doing it because it just makes practical sense,” Rodger notes.

The question of scaling a social enterprise, ever a thorny one, can be particularly challenging in the sanitation sector, however, where startups face enormous cultural, infrastructural, and political barriers to success. Making a waste-based product or service attractive locally can be challenging enough, in the face of long-held cultural norms. But scaling a product or service for millions of people requires more infrastructure, financial resources, and political and marketing muscle than most small startups can independently develop.

“If we are going to have nine billion people on the planet living good lives, we have to get used to the idea of using our resources over and over.”

Take Sanivation as an example. The company was founded in 2011 by Emily Woods and Andrew Foote, who developed a recipe for converting human feces into charcoal briquettes that can be used as fuel. in a market like Naivasha, where Sanivation is based, the solution addressed two problems: unhygienic conditions resulting from lack of formal and safe waste disposal and household fuel needs. Sanivation figured out a way to assign value to something that has traditionally been very difficult to monetize.

In recent years, the company has seen promising growth. It has several full-time waste treatment and fuel production factories and plans to open several more in the near future. It now also has more than 150 staff, 60 of whom are full-time. And in addition to its partnership with NAIVWASS, Sanivation has forged a partnership with the Norwegian Refugee Council to process waste in Kenya’s Kakuma refugee camp-a 20-year old informal city with 170,000 residents and no sewage system.

But Sanivation’s traction hasn’t come easily. In its early days, the company built its waste-to-fuel model around household toilet sales and waste collection services. Expansion was resource-intensive and slow: Sanivation had set a goal of serving one million house holds by 2020, but by the end of 2017, they had reached only 600. Woods, Foote and its other team members had to take a hard second-look at their business model.

“We were not getting the impact we wanted by going house-to-house,” Wood says. “We realized that by partnering with large organizations in charge of sanitation, we could have a much better path to scale.”

Its partnerships in Kakuma and Naivasha are a notable start. In Kakuma, the company has proven that they can provide a service more effectively and cost-effectively than digging pit latrines to handle what would otherwise be a sanitation crisis, says Berner. In Naivasha, however, Sanivation still largely subsidizes its work with NAIWWASS in an effort to prove the model. The company has hope that it can eventually get paid for that type of service.

Multinational muscle

For the Toilet Board Coalition, examples like Sanivation’s of new, decentralized sanitation models at work are exactly what the Coalition wants to see and support. The benefits of such “new grid” models, the Coalition argues, are that they don’t rely on the traditional, costly underground sewer systems or plant-based infrastructure that are common in developed countries. Instead, these models demonstrate that sanitation can be effectively managed with more flexible and cost effective physical and financial structures. What’s more, they prove that the sanitation sector is full of opportunities for entrepreneurs, utilities, waste operators, large businesses, and municipalities alike.

To help early models like Sanivation’s achieve scale, the Toilet Board Coalition launched an accelerator program in 2016. The program, in which Sanivation and social startups like Sanergy in Kenya, Biocycle in South Africa, and Samagra in India have participated, provides mentor ship, and most critically, access to the Coalition’s enormous network of multinational corporate executives.

The reason the Toilet Board Coalition’s accelerator focuses so much attention on relation- ship building with multinational corporations is because the Coalition believes they hold the keys to shifting waste mindsets and habits. It’s worth reiterating that the Coalition’s leadership is largely comprised of corporate executives.

There is nevertheless a case to be made for multinational corporations’ influence: companies like Unilever and Kimberly Clark make the toilet and hygiene products that people around the world use and trust every day.

Small startups, however, don’t necessarily have an easy time building the right connections within these organizations. “You don’t realize just how big a company like Unilever is until you start talking to the people there,” Berner says. “They are almost so big that if l just cold-emailed folks, it would get lost in the shuffle.”

Breaking into that world is also difficult because multinational corporations have strict procurement policies and non-disclosure agreements with their suppliers, she adds.

Berner credits the Toilet Board Coalition’s accelerator with helping Sanivation and its cohort peers find the right corporate contacts and develop those relationships. “As a cohort, we had the opportunity to work with really large companies that are well-trusted around the world. For us to be tied to them gives us the chance to share our learnings in a way that immediately sparks trust among the audience they’ve reached,” she explains. “It was so exciting to have a chance to amplify our message in this way.”

There’s no denying there is a huge market opportunity in bringing better sanitation and products to billions more people. The International Finance Corporation pegs the total global waste management market at $2 trillion-yes, trillion-by 2020. Other researchers and analysts break the dollar figures down into subsector and geographic opportunities: an $80 billion waste-to-energy market by 2022; a $62 billion annual market in India alone, by 2021.

“Any company’s pitch deck will show you that the market opportunity is huge,” says Berner.

With startups like the Toilet Board Coalition’s accelerator participants calling attention not only to the opportunity but pro viding solutions for how to access it, it is not surprising that large companies like Unilever are showing an interest in them. Unilever owned Demestos, which makes toilet paper, soap, and other household products, is a good example. The company’s mission is to increase access to toilets for 25 million people by 2020. “The Toilet Board Coalition fits well within Unilever’s overall brand mission and goals around sustainability,” Berner observes.

Scaling the circular economy

While the opportunity and early momentum for change in global sanitation is clearly there, all of this still raises one question: can the circular sanitation model become not only profitable at scale, but profitable at a lower cost than traditional models?

Rodger believes it can-that is, if entrepreneurs like Sanivation are allowed to engage in the system and make a profit from it, rather than continuing to ask the public to bear the cost of infrastructure and services.

To do this, sanitation needs to be successfully sold as a business opportunity that is attractive to private investors, he says. “The investment then comes more from the private side, as opposed to a city having to go and get some huge loan, from the World Bank [for example), which the city is then saddled with for the next 30 years.”

Based on modeling data from the Toilet Board Coalition’s accelerator cohorts, the participating startups’ business models could be profitable at city-scale, with an eight percent return, on average. If true, that level of return is high enough to attract impact investors as well as some commercial investors.

But recognizing that financial models don’t make the business case as well as successful demonstrations, the Toilet Board Coalition is taking its accelerator a step further in 2018.

“This year, it’s the big picture,” Rodger says. “In 2016, we focused on businesses selling toilets. Last year, we focused on the circular economy. This year, it’s the ecosystem as a whole.”

In partnership with the municipal government of Pune, in India, five startups will have an opportunity to test their sanitation models at city-scale. Rodger says the goal is to help the startups build effective public- private partnerships, build credibility, and establish the infrastructure and resources to prepare for expansion.

“To get to scale, they need legitimacy. If a government appoints an entrepreneur as a

sanitation provider for a portion of the city, they can begin to create the basis for scale. They can get other clients, they can employ people, they get credibility with investors-all the things that sow their foundation,” Rodger says.

In all, the Toilet Board Coalition sees its role in the “big picture” of sanitation as a facilitator for new models’ credibility and scale. “It’s really challenging to work with municipalities, and big organizations and corporations,” Rodger concludes. “We’re trying to see if someone like us can help build that ecosystem.”

Sanivation has evolved rapidly since the publication of this essay. Emily Woods, Sanivation’s co-founder, describes the highlights.

We have truly pivoted to a model that focuses on partnering with local governments to scale safely managed sanitation at a city-wide scale. We take a project development approach of understanding what government partners need, working together to source financing, and delivering and operating those solutions.

We currently have a waste-to-value operating treatment plant in Naivasha Kenya that was built in partnership with NAIVAWASCO. This factory has capacity to serve 10,000 people and is acting as a demonstration treatment facility to show how a circular-economy approach can create much more cost-effective solutions. The current factory was opened at the end of 2018 and treats over 100 tons per month of human waste, converting it to solid fuel briquettes. We now offer a non-carbonized product focused on industrial customers, substituting firewood in boilers. We have sold over 2000 tons of this fuel and have 4 long-term supply agreements with clients.

We have also expanded our capabilities to long-term planning. We lead the creation of a city-wide inclusive sanitation plan both in Naivasha and in Malindi, which help to identify the needs and the phased approach plan to improving sanitation in an area for the next 10 years or longer.

We have MoUs [Memoranda of Understanding] from three cities in Kenya about partnering with them to design and implement improved sanitation solutions utilizing a circular economy approach.

In Naivasha, we are now working on a scaled-up model of our treatment plant that would serve over 100,000 people, producing 1200 tons of sustainable fuel per month. Sanivation contracted Stantec to support in the design of this scaled treatment plant. Together we have designed a solution that can reach over 15 percent EBITDA [earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization] margins for the next 10 years for a capital cost of only [USD] $4 million. We are currently working with local partners to secure the implementation of this scaled model.

For more information about Sanivation, please see their website: sanivation.com.

About the Author

Adrienne Day is a writer, editor and New York native. She has written for The New York Times, New York Magazine, the Village Voice, Stanford Social Innovation Review, and Wired, among other outlets, and has worked as an editor at EW and Spin magazines. Adrienne holds a bachelor’s from SUNY Binghamton and a master’s in journalism from Columbia University.

Jessica Pothering, Demand’s Editor in Chief, contributed reporting to this case study.