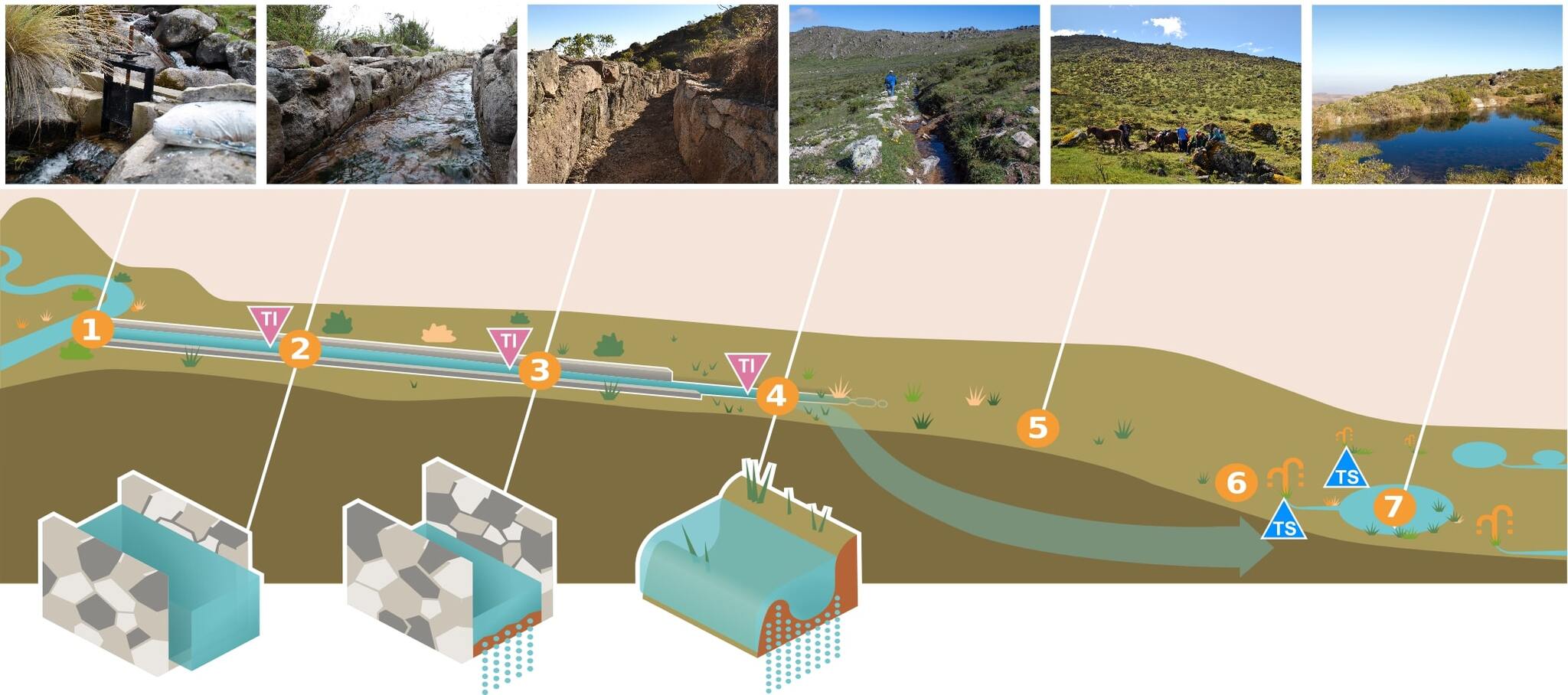

Photo: Musuq Briceño / CONDESAN

Fourteen hundred years ago, a civilization called the Wari built a system of canals to bridge seasonal droughts in what is today’s Peruvian Andes. Rainwater diverted through the high-altitude canals percolated through the Andean rock and soil to reemerge weeks later in communities at lower elevations. As perhaps a recognition of the life-giving necessity of water, the canal networks are called ‘mamanteo,’ Spanish for ‘suckling.’ Peruvian water authorities have eyed the ancient system as a low-cost solution to water shortage in Lima. The state has even invested in revitalizing parts of it. Now for the first time, the plans have the backing of robust scientific evidence.

Upscaling existing pre-Inca systems could help relieve Peru’s wet months of water and quench its dry ones.

Researchers at the Imperial College London in the United Kingdom, with colleagues at the Regional Initiative for Hydrological Monitoring of Andean Ecosystems in Lima, tracked water through the stone canals. With dye tracers, the scientists mapped and timed the water’s slow progress from the mountain town of Huamantanga to rivers that feed Lima’s water supply.

Their findings suggest that water seeped through the mountains for a period of time ranging two weeks to eight months before it reappeared. The average delay was 45 days, according to the research, published in Nature Sustainability.

Peru’s water authorities could scale up the system and reroute and delay 35 percent of the rain that runs off in the wet season, the researchers calculate. That would total about 99 million cubic meters of water each year.

The effort could increase the water supply by 33 per cent in the early dry season, and 7.5 percent for the remaining months. Effectively, the result would be an extension of the wet season, with longer periods for farmers to grow crops, according to the research.

The simplicity of the mamanteo system suggests that this would be a cost-effective way to increase the capacity of existing infrastructure.

Lima could use the help. The city’s population of nearly 10 million people is growing rapidly, straining an already taxed water infrastructure. Lima is the world’s second largest desert city, behind Cairo, Egypt. It is located in a seasonally dry region with a fragile water supply that is vulnerable to dams weakened by erosion and natural disasters such as landslides that cut of streams and rivers. The water shortages have intensified as the city’s population soars, and climate change threatens to exacerbate the problem.

“Upscaling existing pre-Inca systems could help relieve Peru’s wet months of water and quench its dry ones,” the study’s senior author Dr. Wouter Buytaert at the Imperial College London said in a statement.

In this illustration,canals transport surplus water during the wet season to high permeability zones. Water penetrates the soil and emerges in downstream springs after weeks or even months, becoming available during the dry season. Image: Ochoa-Tocachi et al., Nature Sustainability 2019 (used with permission).

The systems cannot be controlled because each depends on the geology of the path the water takes through the ground. But with further study, they can be predictable, and they could enhance the nation’s existing water infrastructure, the researchers write.

“This type of ‘natural infrastructure’ cannot replace traditional solutions such as artificial reservoirs. However, it can make those traditional solutions more effective. In other words: adding mamanteo to an existing reservoir would allow serving water to more people with the same reservoir,” Dr. Buytaert told E4C by email.

“Although we did not do a cost-analysis, the simplicity of the mamanteo system suggests that this would be a cost-effective way to increase the capacity of existing infrastructure. Additionally, it gives additional flexibility, in the sense that it can enhance the capacity of existing systems on a short time scale without the need for major capital investments (such as a new reservoir). This is particularly important for systems which are under high stress from population growth and climate change, as is the case for Lima,” Dr. Buytaert says.

Scaling up the canal networks may be a two-step process, Dr. Buytaert says. Authorities should first study the hydrogeology of each region in question and confirm assumptions the researchers made in their calculations. Then they can restore the ancient systems and build new ones. That process should be straightforward because the technology is simple. The key is to first understand what is underground, Dr. Buytaert says.

For years, Peru’s water infrastructure experts have been aware of the canal systems as a possible tool for modern water delivery, and the state has made investments in research and revitalization. This year, the national sanitation authority SUNASS has committed more than (USD) $20 million over five years to green infrastructure, including restoration of highland wetlands and mamanteo.