A teetering stack of documents on a storage-room shelf can pass for a medical record filing system in some sub-Saharan African hospitals. Looking up a patient’s history can mean leafing through reams of paper by hand. And, if a patient moves or is transferred to a specialist, sharing that history with another medical center can be difficult, or it may not ever happen at all. Digitizing the records would save money, space and time. A patient’s medical history could appear on screen just minutes after they enter a facility. But overhauling the system requires fundamental changes to health care in developing countries.

One of the issues at the core of the matter is how to identify patients. Another issue is how to share medical data between facilities.

When polio or cholera or any disease breaks out in a community the local clinic will be the first to notice the uptick in cases. If clinics can share their records with central hospitals, then a local tragedy in one community becomes data points on a nationwide map. Then medical authorities can respond, and other communities can prepare and try to prevent new outbreaks.

Those two problems – sharing information between medical centers and identifying patients and their medical records – may have a solution. An entirely electronic health data system plus radio frequency identification chips implanted into ID cards for every patient might be a low-cost and simple way to address both issues.

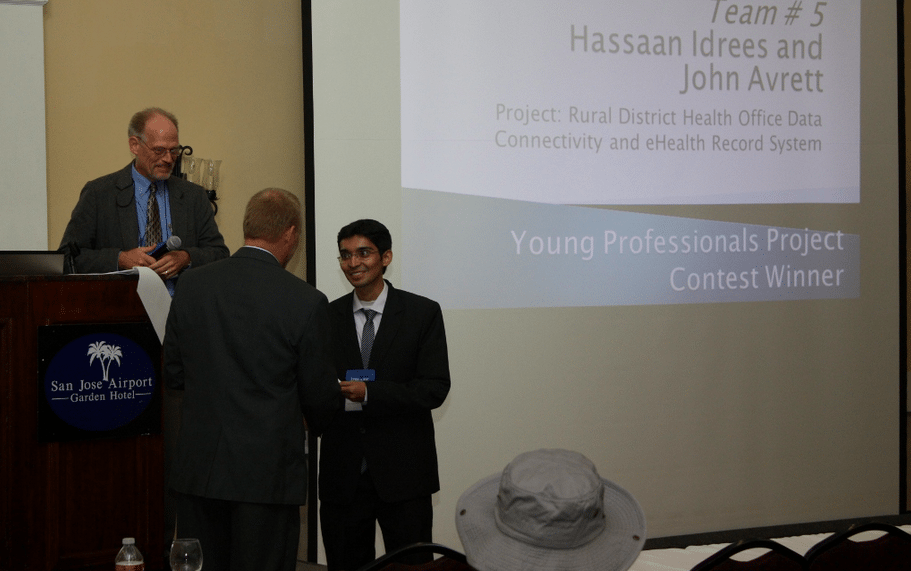

An international team of engineers have volunteered their time to crunch the numbers and solve the problem. They have developed a detailed, low-cost plan, “Electronic Health Record Architecture for Rural Clinic Data Connectivity and Unique Patient Identification,” which won the IEEE Global Humanitarian Conference’s Young Professionals Project Contest.

[Please see their report which is available in two formats: .pdf and .doc.]

“We would say this technology is equally suited to rural or urban areas, but is particularly relevant in a rural setting given the current lack of infrastructure and particularly poor patient outcomes,” Hassaan Idrees, a corrosion engineer trainee at BP, Pakistan and John Avrett, an advanced space technology engineer with the US Air Force, who were both involved in the project, told E4C in a joint statement.

“Our project involves making use of EHR [electronic health records] with RFID for patient identification, and this system was designed keeping in mind the requirements and resources available in rural settings. By avoiding making it highly technical, this system is not training-intensive on health-care workers or doctors, and will not place strain on the local populace, whatever their literacy rate may be,” Idrees and Avrett say.

The team of engineers decided on RFID cards after ruling out nearly a dozen other technologies. Some of those included satellites (poor network performance and high delays), lasers (beam dispersion is easily disrupted by weather and the environment), bluetooth (too many technical requirements such as specific wavelength) and others.

Their system uses standard network protocols on the back of hardware that can be found in or easily brought to rural developing communities.

In the proposed system, three tiers of health care centers would handle data about the patients. The first tier is the rural clinic, the smallest, most basic and most numerous in the system. Patients bring their RFID cards to rural clinics, undergo their procedures and the clinic updates the second tier in the system.

Second tier health care centers are larger district-wide facilities. They collect data from their constellation of smaller rural clinics and upload it to a cloud that all of the clinics in the region can access.

The third tier is a well-equipped hospital in a city that can tap into patient data cloud from all of the medical centers in the region.

“We felt that they gave the plan and presentation with the most focus on implementation and with the most thought-out thinking on financing, costs and return on investment,” says Thomas Coughlin, founder of Coughlin Associates and a specialist in digital information storage and consumer electronics, who was one of the judges for the contest at the Global Humanitarian Technology Conference.

Similar plans piloted in rural developing communities floundered when patients resisted the concept of identification cards. To avoid that problem, the newly proposed RFID system would include public outreach and local laws.

“The earlier projects did not anticipate local opposition to using RFID cards, but ours will incorporate a previously-existing biometric system already enforced by the Indian government in many areas,” Idrees and Avrett say.

The next steps will be to run a pilot program. The team is eying medical centers in Kerala, India, for their test site. With that, the team can make an on-site assessment of the region’s health care needs and find out how much of the proposed system is feasible. But they will need seed funding, they say.

“We would like to give a physical shape to our project by working with federally-endorsed government and non-government organizations. There still are a few gray areas: increased consumer-directed care, new methods of organizing care delivery, and new approaches to financing, but we hope to resolve these with the help of the appropriate stakeholders,” Idrees and Avrett say.

For details, please see the complete report available on our site

Electronic Health Record Architecture for Rural Clinic Data Connectivity and Unique Patient Identification (pdf)

Electronic Health Record Architecture for Rural Clinic Data Connectivity and Unique Patient Identification (doc)