There is a need for improved ethical standards in reporting the results of human-centered research back to participants. The rise of human-centered design and research has improved the field of engineering for global development, both ethically and in the measurable impact of the technologies that have been designed. There is still room to grow, however.

Learn more in this recorded E4C Webinar: Introduction to Human-Centered Design for Engineers

Technology for Development (Tech4Dev) is an expanding field in which engineers aim to improve the lives of the world’s poorest populations via services and technologies. A lack of data in many rural regions, combined with unique cultural context, means that technology development requires human-centered research and field studies. Tech4Dev researchers work with their prospective beneficiaries with the intention to learn from their experiences, inform the sector’s research models, and ultimately improve technology design and implementation for communities worldwide. However, these studies may be a burden for the marginalized populations that often participate in Tech4Dev research. Especially when the research findings do not directly or immediately improve the well-being of the community. Researchers may collect data but then never come back, leaving participants to wonder what happened to the study. There is an ethical imperative to create feedback loops and share study results with research participants.

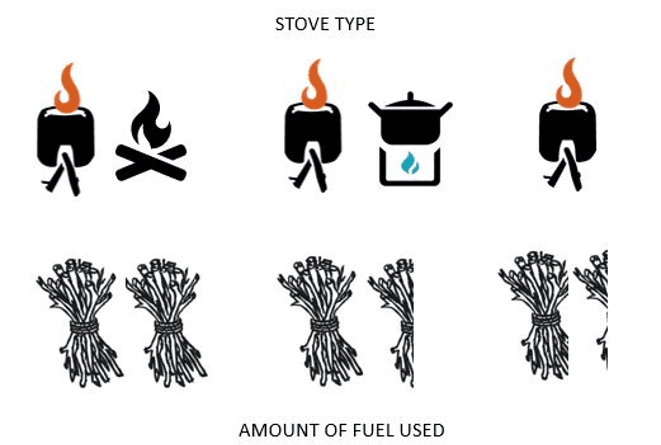

This illustration was used as a visual aid for sharing research results with participants of a study of household cooking habits in Uganda. The image shows the amount of fuel used for each stove combination, controlled for household size. Stove types from left to right: ILF stove and three stone fire; ILF stove and locally mudded stove; ILF stove alone (Ventrella et al., 2019).

One example of such a feedback loop is from a study of household cooking habits in Uganda. P.I. Nordica MacCarty led the research through the Oregon State University (OSU) Humanitarian Engineering Program in partnership with the non-profit International Lifeline Fund (ILF). Jennifer Ventrella, a co-author of this article was on the research team.

The objective of the study was to test the technical feasibility and usability of a sensor to quantify fuel use for different cookstove and fuel types. Sensors were installed in household kitchens, some with people who used just an ILF stove and others who used an ILF stove in combination with either a traditional three-stone fire or a locally made mud stove.

After processing follow-up survey data, the researchers noticed that several participants were asking about the results of the study. Although there was no Institutional Review Board requirement to do so, the researchers ultimately chose to disseminate the results to the community. The OSU team coordinated with ILF to compile results both visually and verbally, recognizing that low literacy levels could be a concern. ILF designed certificates for each participant in recognition of their service. As ILF field staff member Rebecca Apicha reported, “the community was happy to know that the EWS [ILF’s stove] was helping them to save firewood plus related challenges [e.g. emissions and time spent cooking] and this they were already experiencing.”

The experience generated seven lessons learned in designing a method for disseminating study results:

- Visuals – Use visuals to help convey results, especially in populations with lower literacy levels (Figure 1).

- Verbal – Write results in a clear and non-technical manner and maintain consistent communication with field staff and non-profit partner employees to ensure that results are understandable before holding feedback meeting. Then, have the local staff present the results in a format the community is already familiar with (e.g. community meetings with verbal presentations).

- Context appropriateness – Consider whether results should be shared in a community meeting or individually with each participant depending on the content and sensitivity of results. Consult with local field staff and/or local leaders if you are unsure if the data/results are appropriate for a large group gathering.

- Technology infrastructure – Consider whether results should be printed or disseminated digitally.

- Scheduling/time – Work with field staff to schedule meeting(s) at a time that is convenient for most participants, clearly convey that the meeting is not mandatory and just for general interest, and ensure that the information can still be passed on if some would like to but are unable to attend.

- Awareness – Work with community leaders or other representatives to ensure that all participants are informed of the meeting purpose, time, and location

- Content – Share all results so as not to exclude data some might find of interest. If some data are sensitive, consult with local field staff to understand relevance and appropriateness for the community.

This study serves as one example of an endeavor to increase the transparency and ethical accountability of human-focused field research. More examples to inform best practices are needed, however. Two areas that need more attention include methods of building long-term relationships with communities, and stricter standards for distribution of research findings.

Do you have experience disseminating research findings to study participants? Please share your experiences and expertise in the comments below. The authors will be notified.

ILF field staff Jennifer Auma, right, speaks with research participants. Photo: Rebecca Apicha

Further, the community should have a veto to allow or disallow the dissemination of the results beyond their researched community, see step 7 in “Method of Research in a We-Paradigm, lessons on Living Research in Africa.” In: Nielsen, P. and Kimaro, H.C. (eds.) Information and Communication Technologies for Development. Strengthening Southern-Driven Cooperation as a Catalyst for ICT4D. ICT4D 2019. IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology, vol 552. pp. 72–82. Springer, Cham (2019).

Giving the community power to veto the dissemination of study results at first sounds like the responsible thing to do, but giving it a second thought, I’m wondering if that would have an unintended consequence. Researchers and institutions might not be willing to pay for studies that can be canned after they are concluded, which might deter research that could potentially help the communities in which it takes place. Science illiteracy is such a problem, even (especially) in developed regions, that it’s not hard to imagine communities that reflexively veto dissemination of results. Have you come across a problem like that or do you know of a solution or a rebuttal?