Drastically cutting the cost of solar power could put it in league with fossil fuels, and the US Department of Energy is betting on it. The DoE’s SunShot Initiative aims to cut the price of installed solar power generators by 75 percent (of the 2010 cost) by the year 2020. That cost would range from $1 per watt for utilities to $1.50 per watt for homes. But hitting that mark will take more than incremental improvements in the existing technologies, according to a DoE study published in 2012. It will take “revolutionary” change, the study states.

Two US researchers leading that kind of change have improved the efficiency of two different kinds of photovoltaic materials: spray-on inks and a lesser-used thin film material, cadmium telluride (CdTe). Their labs form the Center for Next Generation Photovoltaics, a collaboration between Colorado State University and the University of Texas at Austin.

Solar-power generating window glass

Commercial thin film manufacture typically requires the deposition of gases onto a silicone surface in a vacuum chamber. With a different material – CdTe instead of silicone – and better manufacturing machinery, Walajabad Sampath at Colorado State University is turning ordinary window glass into power generators.

In a multi-junction cell, his technique could convert up to 30 percent of the sun’s light into electricity, he told E4C. In those cells, each junction is tuned to different wavelengths of light so they can convert more of the light that strikes them.

“Our work is making an impact in the PV community. We are taking it away from just a physics focus to manufacturing, high throughput, high volume, lower cost. And hopefully, we would like to bring it down to where photovoltaics becomes a cost-effective energy technology,” Sampath says in a statement.

Spray-on solar inks

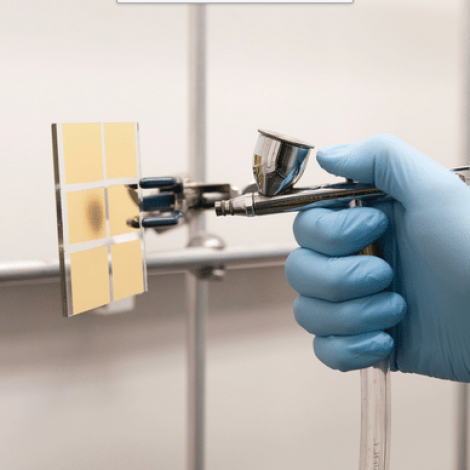

Spray-on nanoparticle inks could cut PV costs down to one-tenth of their price, Brian Korgel, at the University of Texas, said in 2009. The challenge has been to improve their efficiency at converting sunlight into electricity. In 2010, Korgel’s lab had produced inks with 1 percent efficiency. Now, that is up to 7 percent, Korgel told E4C, and the target is 13 to 14 percent.

The cost-savers are the materials and the manufacturing process. The inks could coat cheap substrates such as plastic or rooftops. And manufacture does not require the same cost- and energy-intensive process of gas deposition in a vacuum chamber.

The concept may have potential in a future market, judging by the center’s financial support, most of which has come from businesses. And other researchers are taking up the challenge.

“There are now many groups around the world examining similar approaches and materials as well, so it’s been rewarding to see that our work has inspired many people to work on similar systems and try to make it happen,” Korgel says.

Spray-on solar may have a future in supplying grid power, Korgel says, but that is not the focus.

“We’re also exploring portable PV power applications as well—the kinds of applications that people are thinking about using organic materials for,” Korgel says.

What this means for developing countries

Cheap solar power makes sense for developing countries, Sampath told E4C.

“They are the ones who need it the most because half the population doesn’t have access to electricity. You think about putting up a power plant and wires – to them it’s far more expensive than putting up solar panels,” Sampath says.