Amphibian populations around the world have been declining at a rapid pace, and engineers and scientists are in a race to understand what is happening and how to save these species. Researchers have developed several models and proposed causes for the population decline, but now engineers need to come up with solutions to these problems. While amphibian populations were traditionally represented by small mammals, birds, or fish, these new models give a much more accurate estimate of the current situation. The identified causes of the population decline include new species of chytrid fungi, use of harmful pesticides, habitat destruction, climate change, invasive species, and a possible upcoming mass extinction event. As engineers who want to protect and improve the health of the environment, we need to develop technologies that can monitor the situation and improve our practices to protect vulnerable species.

A study by M. L. McCallum, published in 2007 in the Journal of Herpetology found that the estimated extinction rate of amphibians was 211 times greater than the background extinction rate, meaning human activity is likely to blame for the rapidly disappearing amphibians. Despite knowing amphibians are in danger, researchers often don’t have access to appropriate data regarding amphibian metamorphosis. Most amphibians are hatched in water and metamorphose into an adult terrestrial form, at which point they become sexually mature and can replenish the population.

New models that focus specifically on amphibian populations are needed for researchers to make accurate estimates. One such model was developed by J. Awkerman and S. Raimondo and published in the journal Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety in 2018. Their model can represent how pesticides may impact the development of frogs and what those impacts mean for the population in the long-term.

In another study, this one published in Biological Conservation in 2020, M. G. Agostini and colleagues sought to determine the real danger pesticides pose to amphibians in the wild. They studied four common amphibian species in 91 ponds in central Argentina and found that after pesticides were applied on nearby crop fields, the tadpole populations in the ponds decreased significantly, with some pesticides causing near or complete population death. Of the surviving tadpoles, 93 percent exhibited mobility impairment, which can cause the tadpoles to fail to survive and reproduce in the future. With most common pesticides posing a danger to amphibians, there is a real need for engineers to develop safer pesticides or pest-combating practices.

A paper by S. Gupta and A. K. Dikshit published in the Journal of Biopesticides in 2010 examines the benefits and efficacies of biopesticides, which are eco-friendly pesticides derived from microorganisms and other biological sources. These pesticides have the potential to reduce the damage caused by agricultural practices, but more research and innovation are needed to apply biopesticides to large-scale operations.

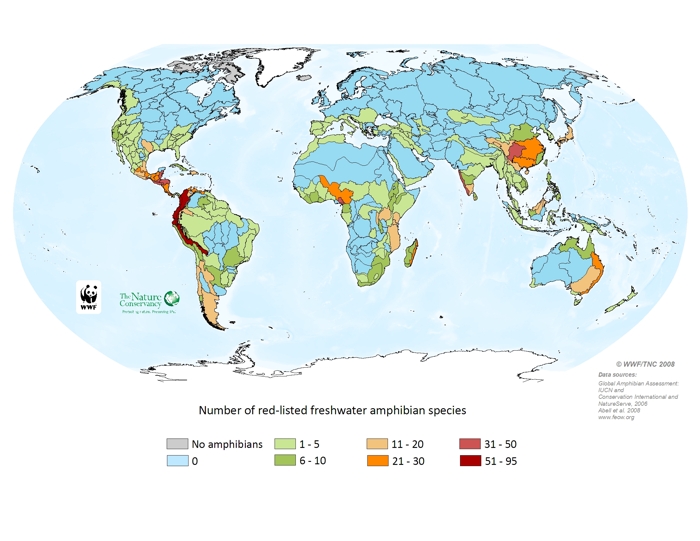

The number of freshwater amphibian species threatened with extinction per ecoregion, according to the IUCN Red List. Find more data and an interactive map at feow.org. Copyright 2008 by The Nature Conservancy and World Wildlife Fund, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Besides pesticides, one of the proposed leading causes of amphibian population decline is the emergence and spread of two species of chytrid fungi. A review published in Nature by M. C. Fisher and T. W. J. Garner in 2020 provides an overview of the discovery of these fungi and the measures that can be taken to stop the spread of the killer fungi. Scientists have estimated that these fungi have caused the extinction of 90 amphibian species and the decline of hundreds of other populations. One tool lawmakers can use to protect amphibians from contamination is to strictly regulate the trade of amphibians across country borders. Scientists are also working on solutions to slow the spread of the chytrid fungi. Methods that show promise include the use of fungicide and environmental disinfectants, vaccinations, and even the use of gene editing to improve amphibian immune responses.

Other possible human causes include habitat destruction, climate change, and the introduction of invasive species. An article written for Live Science in 2011 points out that amphibians are at a disadvantage compared to other types of animals since they require a stable aquatic and terrestrial habitat, and there needs to be a holistic approach to saving them. The decline of amphibian populations may be an indicator that the Earth is entering another mass extinction event, the first one to occur since the evolution of humans. Given this, it may be up to us humans to save the organisms we share this world with.

About the Author

Behirah was an E4C Research Fellow in 2020. She is pursuing a B.S. in Biological Engineering from the University of Missouri, and has worked in an ecology lab and on a soybean breeding research farm. She is currently developing a research seed planter that can be used in low-budget research farms.