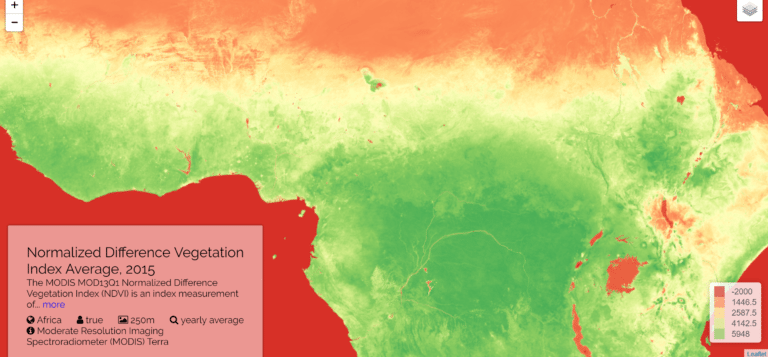

Spraying insecticide indoors remains one of the most effective weapons against malarial mosquitoes, the World Health Organization says, but sprayers need guidance. The Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team (HOT) took up the challenge. In a nine-month push that started in December 2016, more than 3700 volunteer and professional mappers are identifying mosquito hotspots in regions that total 500,000 square kilometers in southern Africa, Southeast Asia and Central America.

HOT partnered with the satellite imagery enterprise DigitalGlobe and two global health organizations, the Clinton Health Access Initiative and PATH. Thus far, the mappers have hosted more than 50 public Missing Maps mapathons worldwide, and they have tapped university student labor with monthly YouthMappers events. The work has generated a colossal number of maps of buildings and urban mosquito hideaways. HOT updates its statistics by Twitter and at the time of publication the tally is 3 million buildings.

How to map mosquito hot spots

Much of the mappers’ work is with satellite images, which can be done from anywhere in the world. Although there is some on-the-ground field work by local mappers.

“The requesting organizations are really only interested in building enumeration and we can do that remotely, basically tracing building footprints from imagery,” says Russell Deffner, HOT’s project manager for the Malaria Elimination Campaign.

The effort spans the globe. Mr. Deffner is based in Colorado, USA, and he coordinates a team in Dar es Salaam Tanzania, Jakarta Indonesia, and five YouthMapper chapters in Kampala, Uganda.

“In general, it’s a ton of fun to map with the almost 4000 people who have contributed, most I never hear from, but quite a few reach out to ask various questions about the imagery, what they might be seeing in a particular place, and generally how their contributions will help end malaria,” Mr. Deffner says.

A digital cartographer’s toolkit

Cellular service is notoriously spotty in many of the places where the mappers operate, but there are workarounds.

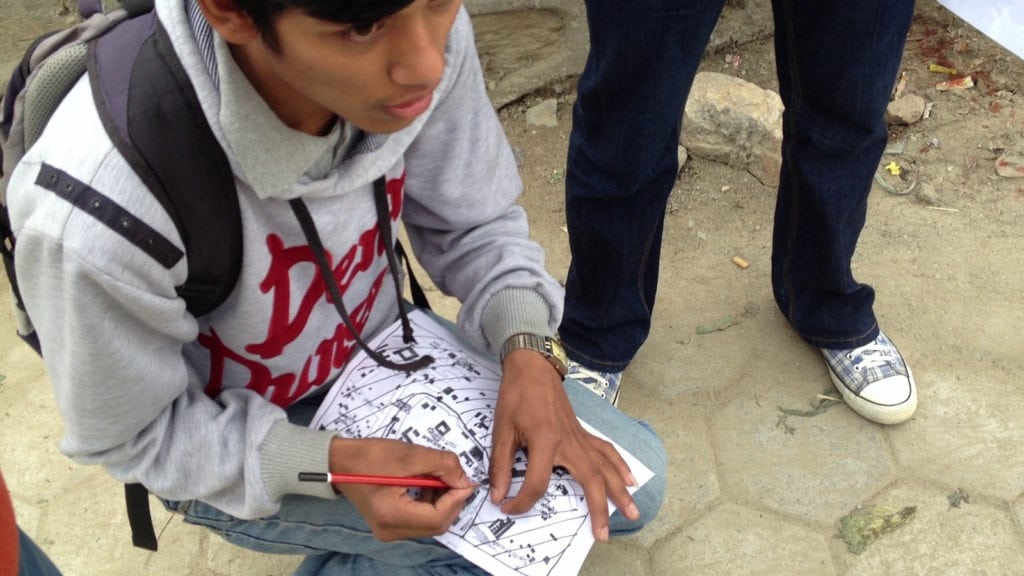

“GPS is reliable globally, except under tree and sometimes building cover, so collecting data that way is fairly easy if you have the tech,” Mr. Deffner says. “Smart phones are less reliable, but maybe more readily available in the developing world; but we have a very low tech solution that also works anywhere, and that’s pen and paper.”

His mapping teams use the paper-to-digital platform Field Papers for exploring and mapping places both online and offline. On the opposite side of the technology spectrum, the mappers might instead use the higher-tech Portable Open Street Maps application on smart phones. They couple POSM with Open Data Kit and Open Street Map for a field-ready online or offline tool.

“If we’re helping a local community just getting started with limited funds, most likely we’d go low-tech, show them basic editing and field data collection using fieldpapers and gps/smartphone. If we’re going in to do a fast-paced major data collection campaign, we’d probably go in with ODK/OMK on smartphones with POSM as central data collection and editing offline to be uploaded all at once when we’re back from the field,” Mr. Deffner says.

How to get involved

Mapping is ongoing and anyone can take part. Find mapping tasks at tasks.hotosm.org and in the MapSwipe app. Companies can get involved by hosting mapping parties and events. For information, please contact info@hotosm.org.