A single weather event does not prove climate change, but the heatwave that is hitting much of the Northern Hemisphere this summer and triggering forest fires from California and Canada to Portugal, Greece and Sweden is focusing attention on the need to kick our collective carbon habit. Even without climate change, it just makes sense to transition from fossil to renewable energy sources.

Take water pumping technology in rural areas of Africa, Asia or remote islands in the Pacific Ocean or the Caribbean. The people of these areas have historically made a negligible contribution to global greenhouse emissions and yet they stand to bear the brunt of rising seas and destabilized rainfall patterns. However, it is more immediate needs that make solar power attractive—cost and convenience. Diesel for submersible pumps is dirty and expensive, and handpumps are inconvenient and tiring.

The time for solar pumps has come. The need is here, the technology is here, and the cost of that technology is making it viable and attractive.

Although solar pumps have been around for many years, their time has come. The need is here, the technology is here, and the cost of that technology is making it viable and attractive. That’s why in our latest, RWSN Strategy (2018-2023), we have a Topic dedicated to pumping, and solar pumping in particular, led by Andrew Armstrong at Charleston SC-based charity, Water Mission who recently wrote about Demystifying Solar-Powered Water Pumping.

An early win has been the publication last month of a new “Solar Water Pumping Miniguide” compiled by Alberto Llario at the International Organisation for Migration (IOM). This colorful and accessible manual outlines the steps to design water supply systems based on solar pumps, particularly for humanitarian situations, and complements “Solar pumping: the basics” by the World Bank also published this year.

Meanwhile, at this year’s 41st WEDC Conference in Kenya, Doug Lawson of Water Mission led a packed one-day training event on solar pumping that attracted NGO and government staff from across East Africa and beyond. This built on an earlier session at the 7th RWSN Forum in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire in 2016, that included great presentations on UNICEF’s experiences globally, as well specific experiences from Zimbabwe, Malawi, and West Africa. A key point made in the latter, by Jacques Louvat of Swiss NGO, Helvetas Intercooperation, is that when a community handpump fails, users go back to their traditional, unsafe, water sources, but the experience with solar-powered pumped systems is that users become so attached to the convenience of water in the home that they are willing to pay for a better service and push to get breakdowns repaired.

Despite some notes of caution, there was a common view that while the humble handpump will be around for many years to come, the future is in the sunshine.

The roll of convenience as a driver for water supply sustainability is one that deserves more attention. With that in mind, through the RWSN Sustainable Groundwater Development community we organized an e-discussion in June 2018 to draw together experiences from our diverse membership. The lively three-week debate raised many important issues, including:

- Most of the challenges relating to solar-powered water schemes are common to all types of rural water systems and can be addressed with measures like stronger governance, private sector involvement, and “smart” pre-paid water dispensers;

- Although capital costs of solar pumping are well understood, less is known about recurring costs and only a few evaluations have been published which report on the full lifecycle costs. Those include the 2016 UNICEF evaluation of 35 solar pumping schemes across four countries (pdf), the 2017 Global Solar and Water Initiative evaluation of 40 solar pumping schemes in Kenya, and the 2017 Water Mission study of 85 solar pumping schemes across eight countries (pdf);

- There are only a few studies on the social aspects of solar-powered water pumping, such as perceptions of end-users and whether the technology has any impact of equity, inclusion or gender power dynamics. For example, see the International Water Management Institute’s 2016 study in Ethiopia that found that solar pumps near homesteads were women’s preferred technology; a 2018 field report from farms in Dhundi (pdf), in the state of Gujarat, India, that analyzes gender and social issues in a community cooperative that sells surplus solar energy back to the grid to avoid over-pumping; and a 2016 UNICEF evaluation of 35 solar pumping schemes across four countries;

- The environmental impacts of solar pumping on water resources needs further study to ensure that management and regulation balances competing needs and demands for water;

- There is experience of using solar pumping in agriculture so we potable water supply professionals need to reach out to our colleagues in farming and irrigation to share experiences and find common ground for collaboration – particularly on “Multiple Use Systems”, income generation, scaling-up, training and regulation.

Overall, despite some notes of caution, there was a common view that while the humble handpump will be around for many years to come, the future is in the sunshine.

Does this mean that Solar is the best option everywhere? No—technology and context have to match up for successful scaling-up and sustainability. It is also imperative that solar pump systems are properly sited, designed and managed. A practical way of finding out whether conditions are right for scaling-up technologies, such as solar pumping, is through the Technology Applicability Framework (TAF), an open-source tool to help innovators, program managers and governments.

Three case TAF case studies on solar from South Sudan, Uganda and Ghana showed that while demand and potential for growth is high, there are skills shortages—a lack of trained technicians and local government water officers need to understand what they are regulating. It appears that the situation is changing rapidly, with an increasing number of university and private sector training programs for solar technicians. Age-old barriers persist, however. There is a shortage of skilled technicians in rural areas, and a gap in understanding of the opportunities and limitations of the technology at higher levels of decision- and policy-making. The skills gap is daunting, and care is needed if water resources are to be managed sustainably.

Climate change is challenging us all in many different ways, and while technology often creates as many problems as it solves, the future looks bright for solar-powered water systems. To learn more, please visit the World Bank’s briefing and Knowledge Base for solar pumping and join RWSN’s Sustainable Groundwater Development community.

With thanks to Andrew Armstrong, Dough Lawson (Water Mission), Emily Bamford (UNICEF) and Kristoffer Welsien (World Bank) for their helpful comments and links.

About the Author

Sean Furey is a Contributing Editor at Engineering for Change and Director of the Rural Water Supply Network (RWSN) Secretariat at the Skat Foundation, St. Gallen, Switzerland.

Now you have reached.Once you tested in Kitale and it worked well,then move close me in Bungoma where there is scarcity of water.You will save families.

The greatest reliable boost in the agricultural sector is the use of solar powered water pumping technologies. these pumps can be submersibles, surface and many options including the hybrid systems. In Uganda, you can find these solutions and reliable services for the water sector, agricultural, and institutional at Innovation Africa Limited. Thank you Sean for this educative information.

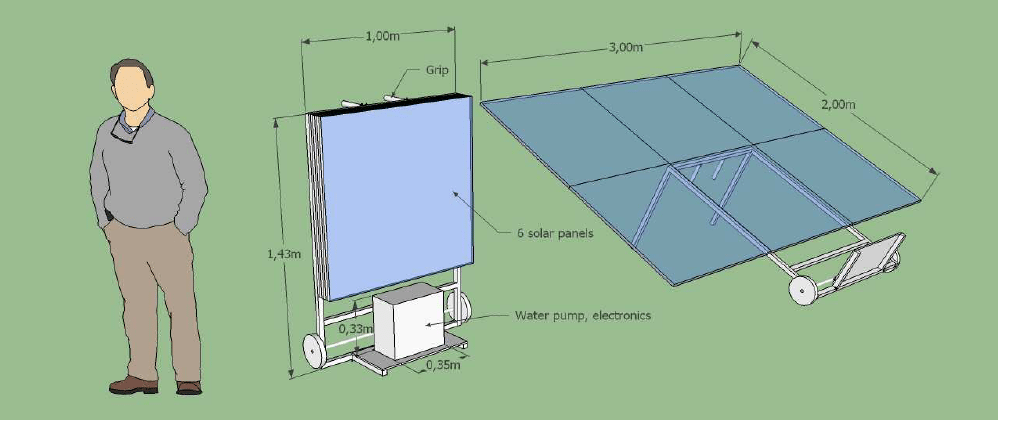

Great piece. Does anyone know what the name of the solar pump pictured in this article?

Excellent initiative to a better environment which is renewable and sustainable .

Nice Piece, i found extensions(documents) that have proved quite interesting apart from this main material.

Thanks for the positive feedback – we are always on the lookout for guidelines (particularly in other languages) and independent evaluations. You can share on the RWSN Sustainable Groundwater Development group (https://dgroups.org/rwsn/groundwater_rwsn) or to me directly.