Earlier this year, we withdrew from guest editing a special journal issue on failures because the publisher’s practices were racist. What we learned shows pervasive issues, and a few glimmers of hope.

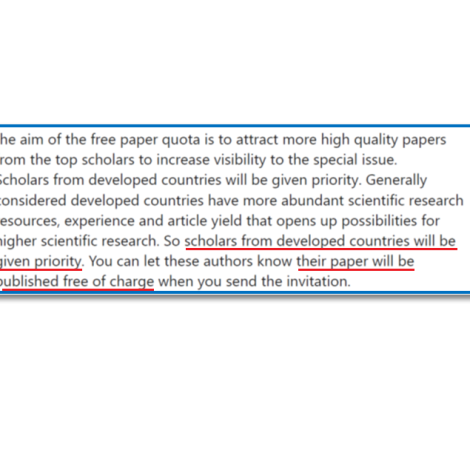

At the beginning of the year, we were excited about the opportunity to publish a special issue in MDPI’s International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health (IJERPH) on Learning from Failures in Environmental and Public Health. The opportunity was particularly attractive given that it came with fee waivers for five open access papers. To cut a long story short (you can read the whole saga here), when we began working on the special issue, we discovered that MDPI had provided those fee waivers “to attract more high quality papers from the top scholars … so scholars from developed countries will be given priority,” according to an email a representative of the organization sent to Dr. Dani Barrington (one of the authors of this article). We withdrew the special issue.

Researchers and practitioners in low- and middle-income countries often have the odds stacked against them when they try to speak on the public stage of international development.

As a team, we talk about failures a lot. In certain professional circles, we are known for our failures gameshow at international WASH conferences and for the Nakuru Accord, a pledge that WASH professionals can sign to share failures and learn from one another. So we stuck to our word and started to write about our experiences. After we drew attention to the situation, MDPI responded on Twitter to say an internal investigation found that this practice was being carried out by “some of the editors handling special issues,” and that MDPI “do not support this practice and it has been clearly stated internally to prevent it from being used again.”

Yet, we have heard numerous stories that show this wasn’t a one-off. We heard from a researcher at a South African university who was told that his paper could be given a waiver, but only on the condition that his more highly published European co-author replaced him as corresponding author. Time and time again, we heard from other guest editors who had been (and continue to be) told that fee waivers are reserved for “high-profile” authors. We heard from an ex‑MDPI Assistant Editor who noted that these unethical practices were caused by pressure to “publish papers like McDonald’s makes burgers.” This was clearly not the result of a handful of rogue editors, as MDPI’s ‘spin-vestigation’ suggested.

Sadly, we recognize that the racist practices in international development publishing and research only mimic the racism present in the international development sector.

In international development, we hear repeatedly how local leaders with local solutions to local problems are what will end poverty, yet researchers and practitioners in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) often have the odds stacked against them when they try to speak on the public stage of international development. In the words of Arundhati Roy, “There’s really no such thing as the ‘voiceless.’ There are only the deliberately silenced or the preferably unheard.” We need to stop silencing the voices to which we should listen most carefully. How do we do that if publishing is stacked against them as well?

After speaking up about our experience with IJERPH, we were approached by several publishers and journals interested in hosting the special issue on failures. Rather than fall into the same trap again, we decided that we would speak to all of the editors to check if we were happy with their publishing practices before choosing a journal. All of the publishers that we spoke to subscribe to Research4Life or a similar fee waiver program that gives authors from low-income countries 50 percent or more off open-access fees. Many of them were also able to offer a small number of fee waivers that could be used at the discretion of the guest editor for special issues. The details of these offers are shown in the table below.

| Publisher (and Journal) | Model? | Usual OA fee? | LMIC support program? | Additional fee waivers offered? |

| BMJ (BMJ Global Health) | OA | $3790 | Yes (HINARI, part of R4L) | None |

| Hindawi (Journal of Environmental and Public Health) | OA | $1350 | Yes (R4L) | Some offered for special issues |

| IWA (J WASH Dev, Water Quality Research Journal) | Hybrid | $1850 | Yes (R4L) | Some offered for special issues |

| PLOS (PLOS One) | OA | $1695 | Yes (PLOS GPI) | Offered on case-by-case basis |

| SAGE (Environmental Health Insights) | OA | $1500 | Yes (R4L) | Some offered for special issues |

Table 1: Open access (OA) fees and waiver models adopted by selected publishers; R4L = Research4Life, GPI = Global Participation Initiative

This experience showed that there are publishers who are looking for ways to support researchers from LMICs, and we would encourage guest editors on special issues to ask about the opportunity for discretionary fee waivers to further support LMIC researchers and practitioners to share their findings in open-access journals. These fee waivers can support those researchers who are often not heard because the system is stacked against them, whether because they are from LMICs or from non-academic research backgrounds.

This experience showed that there are publishers who are looking for ways to support researchers from LMICs.

Researchers from high-income countries (HICs) should support their LMIC collaborators to be authors on research publications. Too often we see studies carried out in LMICs that are authored solely by HIC researchers. This is extractive: if local researchers carried out the data collection, they deserve credit for their work. Don’t make them fight for the recognition they deserve; the excuse of insufficient input to merit authorship is just that – an excuse. HIC researchers can support and mentor LMIC research collaborators through the data analysis and writing process. If you are genuinely interested in changing the world with your research rather than simply building your own profile, this is a fantastic way to have lasting impact.

If we only report positive results, we are trying to build while only being able to see half the picture.

Finally, all researchers and practitioners need to recognize and share failures in their work. Research is all about trying new things and building on the work of others. If we only report positive results, we are trying to build while only being able to see half the picture. If failures are ignored or played down, others are doomed to repeat those failures. The result is a waste of time, money and resources that the international development sector cannot afford. After speaking to various publishers, we selected Environmental Health Insights as the new home for the special issue on Learning from Failures in Environmental and Public Health. With the support of a sponsor, we hope to ensure that no authors will have to pay open access fees.

Sadly, we recognize that the racist practices in international development publishing and research only mimic the racism present in the international development sector. There is a much wider discussion to be had about the ‘whiteness’ of international development and the racism and neo-colonialism that perpetuates in the sector. All of us must consider these failures and how we have arrived at this point. After all, it is only by learning and sharing these failures and the hard lessons bound up with them that we have a chance to achieve real change and development.

The authors are working with the Journal of Environmental Insights on a special edition about Learning from Failure in Environmental and Public Health Research. See the call for papers.

About the Authors

Dr. Rebecca Sindall is the Operations Manager for the Engineering Field Testing Platform in Durban, South Africa. The platform tests sanitation prototypes in informal settlements and rural households. Her other interests include disaster risk reduction and drowning prevention in LMICs.

Dani Barrington is a Lecturer in Population and Global Health at The University of Western Australia. She uses interactive methods to understand people’s experiences with toilets, menstrual health and hygiene, incontinence, water and rubbish management. Her participatory research and teaching focuses on ensuring that everyone has access to the services that they want to use, regardless of their income or the country they call home.

Esther Shaylor is a water and sanitation engineer working as an Innovation Specalist in WASH and Education at UNICEF in Nordhavn, Denmark. Her focus is on designing and implementing innovative solutions to WASH challenges in resource-poor environments. She has a technical background combined with systems thinking to deliver programs which encompass markets and livelihoods, and bridge the divide between humanitarian response, emergency preparedness and development.

Wow, glad the special issue found a new home! As a new academic, I was shocked to find out that discrimination by national origin could even be allowed. As a graduate student in a western university, do you have any suggestions for what we can do? Our advisors/supervisors are typically the ones who select the journals and co-authors – I want to do what I can to push the field to be more progressive in publishing, but that relies heavily on those more established in the field.

Hi Anna,

Thanks for your comment! Ethical research really shouldn’t allow discrimination in this way. In this case, the profit incentives of the journal appear to take priority over ethical publishing practices. I would suggest that even as a early career researcher, it is possible to voice your concerns about the inclusion/exclusion of co-authors and the journals that your work is published in. Be clear on what your university’s ethics board says about authorship (Elsevier authorship guidance, the Council of Science Editors (CSE), and the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) all agree on the same basic principles) and highlight this when you are discussing authorship with supervisors. The Elsevier CRediT statement is a useful way to gauge who did what when drawing up a paper’s author list. When it comes to selecting journals, there is less clarity. Check Beall’s List for predatory journals, share information like this blog with researchers if they are considering a journal that appears to have operated in ethically dubious ways in the past, and remind researchers that where they publish affects how the research community sees them. Working in ethical ways benefits all of us, and increases trust in our work, within the research community and outside of it. For a quick and easy overview of what ethical research practices look like, The Singapore Statement on Research Integrity is a good starting point, but your university almost certainly has a code of research conduct that covers many of the same points. By referring to this documentation when you are discussing potential issues with more senior researchers, you demonstrate that you care about doing things the right way, which hopefully opens up a conversation about what that looks like and how all of us can contribute to improving our community.

Thanks,

Becky