Trend analysis on African transportation by Engineering for Change in partnership with Yamaha Ventures

Like anywhere, personal transport in Africa is a blend of different modes. Some of the most popular are motorcycle taxis, commuter taxis, personal vehicles, auto-rickshaws, and non-motorized means like cycling and walking. The continent’s transit sector is evolving with the emergence of new transport modes such as Bus Rapid Transit, light rail systems, and e-ridesharing. Even the use of unmanned aerial vehicles is entering Africa’s transport landscape, with a number of foreign organizations currently piloting drones, particularly for medical deliveries.

The sector is not without its shortcomings, and a few of these include fractured road networks that limit access to work for a significant portion of the population; decreasing air quality in major cities due to increasing motorization; and inadequate safety measures, especially on roads, resulting in a high accident incidence rate.

Countries across the continent are becoming more aware of the need for a holistic approach to solving transport issues. Governments are revising transport policies in order to better integrate non-motorized and motorized transport modes, like creating dedicated city walkways and building more efficient mass transit networks like Bus Rapid Transit. This represents a policy shift from the historical trend of increasing (costly) road network expansion.

A few countries are even taking steps to improve their own transport manufacturing capabilities, though these endeavors are still in the early stages. The majority of transport products in Africa are imported. Vehicle assembly, however, is growing on the continent, which creates jobs for local workers.

This study examines current transport patterns and trends in Africa, the causes and effects of these patterns, and how transit problems are being solved.

The current market

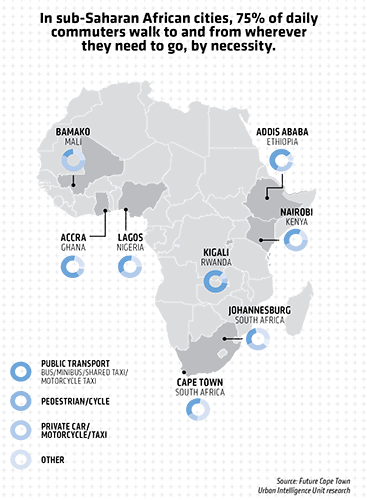

Forty percent of the continent’s one billion people live in urban areas, a figure that is rising quickly. By 2030, 50 percent of Africans will be urban dwellers. What’s more, anywhere between 30 and 55 percentof sub-Saharan Africa’s urban residents are classified as living in poverty, and an even larger percentage of the urban population, 72 percent, live in densely populated slums, where roads are generally unpaved, narrow, and poorly maintained. As urban sprawl grows, so do these inadequate and deteriorating road networks.

Urban populations rely on a combination of motorized and non-motorized transport. Most motorized vehicles travel by road, which carry 80 percent of goods and 90 percent of passengers on the continent via motorcycles, cars, auto-rickshaws, and buses. Motorcycle taxis are one of the most popular modes for commuters because of their ability to maneuver through traffic jams. In one study, motorcycle and auto-rickshaw maker Bajaj Auto identified a correlation between a country’s per capita GDP and the popularity of motorcycle taxis.

Drones are in a nascent stage of transport integration on the continent, and are primarily being tested in delivery markets — for medical supplies, for instance.

Primary forms of non-motorized transport include walking and bicycles. These modes also sometimes involve the use of physical products, like handcarts, to move goods. “Head loading” for walkers is a common way to move physical bundles.

There are socio-economic differences in how transit is used in African cities, as elsewhere globally. More than 75 percent of total daily trips made by Africa’s poor are by walking, compared 45 percent by the more affluent. Despite the large percentage of the population relying on non-motorized transport, pedestrian and bike-friendly city infrastructure is uncommon or in a poor state. When the poor use motorized transport, they often rely on communal or motorcycle taxis.

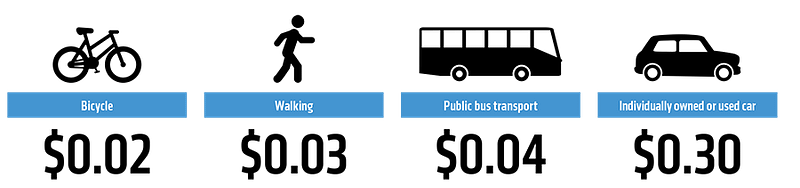

Communal taxis and moto-taxis are also popular at higher income levels, accounting for between 75 to 80 percent of Africa’s total motorized trips. This is consistent with the continent’s low rates of car ownership: 30 to 70 vehicles per 1,000 people, according to a 2011 survey of Kampala, Lagos, and Douala. The cost of personal car ownership is an order of magnitude higher than other non-motorized or public transport options and is cost prohibitive for a large portion of Africans.

Even without car ownership, transportation in Africa is expensive. In Lagos, commuters spend 40 percent of their income on transportation on average.

Overall, the motorization rate on the continent is low by global standards. The motorization rate is about 44 vehicles per 1,000 inhabitants, far below the global average of 180 vehicles. As of 2014, there were only 42.5 million registered vehicles in Africa.

Average cost per commute in Africa, by transit type

There is significant growth in demand for motorized services, however, which could be attributed to several trends: a lack of cycling culture and infrastructure to support it; and social factors that put a premium on motorized transport options and view non-motorized transport options as symbols of poverty. Public policy also reflects these opinions: transport policy proposals for non-motorized transport routes are often overshadowed by plans for motorized sector development in most African countries. Bike sharing programs also remain largely unexplored.

The demand and growth of largely unregulated, informally provided, non-conventional shared transport — the dominant method being the motorcycle taxis — suggests that formal public transportation is inadequate.

Transit risks

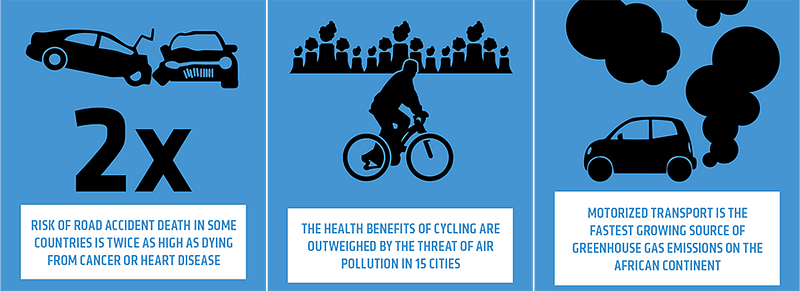

The current state of the transport sector in Africa is having a significant impact on the environment and the health of the population in urban and peri-urban areas. According to a report from the U.N. Economic and Social Council, the global motorized transport sector accounts for 20 percent of greenhouse gas emissions and has become the fastest growing source of emissions in Africa. The construction of infrastructure to support motorized transport also affects water drainage systems and geological formations. The report also claims that building this infrastructure almost always results in destruction of forests and wildlife habitats and causes land degradation through soil erosion on surrounding land.

Motorized transport also produces localized pollution that can have negative impacts on human health. According to a report from the World Health Organization, epidemiological and toxicological studies indicate that transport-related air pollutants contribute to an increased risk of death, particularly from cardiopulmonary causes, and increased risk of non-allergic respiratory symptoms and disease. In least 15 African cities, including Kampala, Kaduna, and Bamenda, air pollution has become so bad that the potential health hazards of cycling outweigh the potential health benefits.

As a result of increasing motorization and vehicle ownership in African cities, traffic jams have become a persistent and paralyzing problem. South Africans lose about 90 working hours per year sitting in traffic. In Lagos, traffic jams reportedly cause significant commuter price fluctuations. One commuter in the city told E4Cthat a trip costing $1 during off-peak morning hours can cost up to $3 in peak afternoon.

Africa also has the highest number of road traffic accidents per capita. Road traffic accidents are responsible for over 1.2 million deaths per year globally. Of this number, over 225,000, or 19 percent, occur on African roads. According to a report from the University of Michigan, the likelihood of dying in a road accident in several African countries is almost twice as high as dying from cancer, heart disease, or stroke. In Kenya, for example, road accidents claim lives 80 percent more often than heart disease, and a 20 percent more often than strokes. Other countries like Burundi, Uganda and Zimbabwe are similarly affected.

Transport drivers

A variety of socio-economic factors influence transit user behavior of low-income commuter groups. The main drivers include:

— Urbanization: The size of Africa’s urban population is on the rise. Mass transit options in urban centers such as buses and light rail are insufficient and do not serve the last mile. The emergence of megacities with populations greater than 10 million, like Lagos, makes urban areas increasing difficult to maneuver by foot. Informal, low-cost alternatives to walking for low-income individuals primarily include motorcycle and bicycle taxis.

— Price: People living in extreme poverty can only afford to use non-motorized transport means, such cycling or walking. To transport goods, they rely on hand-carrying and head-loading.

— Inadequate public transport systems: Door-to-door public transportation is inadequate in most African cities. The relatively high cost of motorcycle taxis means that average earners have to combine the use of minibuses and motorcycle taxis for most journeys.

— Traffic jams and road safety: Persistent traffic jams in major cities across Africa influence commuters’ preference for flexible ways to get around, for example, by motorcycle taxi. Traffic jams also result in considerable loss of time and productivity. Africa also has the highest number of road traffic accidents per capita globally. In spite of the convenience of motorcycle taxis, which can circumvent traffic jams, commuters are wary of over-dependence on them because they can be dangerous. Motorcycle taxi accidents are the leading cause of head injuries in Mulago Referral Hospital, Uganda’s largest hospital, for example.

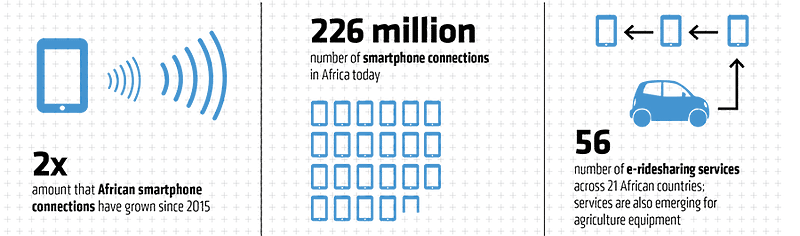

— Smartphone adoption: The number of smartphone connections across the continent has almost doubled since 2015, reaching 226 million. Rapid adoption of the smartphone has created new opportunities to track and provide transport support to customers.

The evolving commute

The product landscape in the African transport sector is comprised of a wide range of products and is dominated by conventional, long-existing products like bicycles, motorcycles and commuter taxis. Emerging solutions include Bus Rapid Transit, light rail transit and drones for medical and logistics purposes, as well as infrastructure-focused social enterprises and ICT-enabled transport solutions like ride-tracking platforms.

Small scale vendors rely heavily on motorized vehicles for access to shops and to deliver goods from suppliers to customers. Africa’s insufficient public transportation systems are creating opportunities for entrepreneurs to launch alternative transport products. Informally, product hacking is common because most available transport products are not designed for the African market and products therefore have to be customized to meetusers’ needs. Many of the common adaptations to motorcycle taxis, handcarts, and auto-rickshaws are unsafe, however.

Formally engineered designs like the Tryctor, a motorcycle modified into a tractor, have also arisen. Other low-cost personal transport products include bicycles such as Bandha Bikes, Mozambikes, Buffalo Bicycles, which are designed to be durable and inexpensive. Buffalo Bicycles currently has over 30,000 bicycles in circulation in Zambia and has dealerships in other African towns, such as Kisumu, Kenya.

Use of motorcycles for personal and commercial transport is widespread. A 2012 study by Credit Suisse on motorcycles in Africa identified a correlation between per capita GDP and growth volume of motorcycle sales in African countries. The volume of sales accelerates at $1,000 to $5,000 per capita GDP and slows then reverses after the $10,000 threshold.

As a result of the high cost of transportation in urban areas, informal shared mobility solutions are common, and technologies are evolving to improve them. Shared mobility modes range from small three-seater auto-rickshaws from Mellowcabs and the Re4S Tuk Tuk from Bajaj Auto, to full-size vehicles and buses such as the Mobius II from Kenya and the Kiira EV Smack and Kayoola Solar Bus from Uganda. These technologies are increasingly electrified, rather than relying on gasoline or diesel, with the aim of reducing operating costs and improving air quality in cities. Uganda is pioneering in the design of electric cars, while Kiira Motors Corporation in South Africa currently leads in the number of electric vehicles, both locally manufactured and imported, in Africa. Kiira had about 290 plug-in vehicles on the road in 2016 and aims to reach three million by 2050.

Tech-enabled ridesharing

Ridesharing is not new on the continent; informal ridesharing, most popularly in the form of commuter taxis, has long been in existence. Indeed, Africa’s public transit systems are primarily comprised informal commuter taxis and motorcycle taxis.

There is a widely acknowledged need to improve the many informal transport networks, however. In response, a number of ICT solutions are being developed to both map and track public transportation options. Examples include Flashcasts in Kenya, which tracks vehicles as they move through neighborhoods to inform riders of stops, and WhereIsMyTransport.com in South Africa, which does mapping. Whereismytransport.com captures data such as transport routes, fares, and frequency of public transport, focusing on informal means like commuter taxis and auto-rickshaws, and adding this data to available data for formal transport systems like rail, bus and Bus Rapid Transit.

Africa now also has more than 50 e-ridesharing services in 21 countries. Ridesharing apps are becoming increasingly popular among the middle-class in urban areas. Coverage is still limited, however. In Uganda, commuters are only able to use Uber within the capital Kampala and some surrounding peri-urban areas. While e-ridesharing is still unaffordable for most lower-income groups, new solutions are starting to address the needs of these customers. Sendy and Mondo Ride utilize motorcycle taxis, in addition to cars, as a part of their service, while Fone Taxi and ZayRide offer three-wheel ride options. These apps rely on local expertise and understanding of local habits to attract customers.

Commercial vehicle sharing, for farmers for instance, is also possible now. A majority of Africans depend on agriculture to earn a living. Many are unable to afford modern or sophisticated equipment, however. One app, Hello Tractor in Nigeria, allows a tractor owner to lease out his machine to farmers in need for a specified period of time.

To address road safety and traffic accidents, services like Traveler and Smart Matatu monitor driving conditions and alert system operators to unsafe conditions. SafeBoda is a ride-hailing app that provides information about motorcycle taxi drivers, and offers a ratings system for drivers and passengers. SafeBoda taxi operators receive road safety training and are equipped with two helmets: one for the driver and one for the passenger. Hardware-based solutions include producing low-cost motorcycle helmets like the BePro motorcycle helmet by Design Without Borders.

Formal mass transit

Use of Bus Rapid Transit and light rail is still limited across Africa, but these systems are gaining popularity, with governments in South Africa, Tanzania and Ethiopia investing in these modern public transit modes. Dar es Salaam and Johannesburg have already installed Bus Rapid Transit systems and sub-Saharan Africa’s first light rail system was set up in Ethiopia in 2015. These developments could potentially leapfrog conventional public transit modes like city busses in a number of African cities.

The poor state of transport networks and frequent need for repairs on roads in rural areas requires innovative, decentralized solutions to extend and maintain current infrastructure, however. Emerging solutions include Mobilized Construction, a startup leveraging software to coordinate local teams to execute road repairs on unpaved roads in rural areas. Disjointed transport networks also leave many rural areas without access to services like healthcare and education. Support services by organizations like Bridges to Prosperity are trying to address this need.

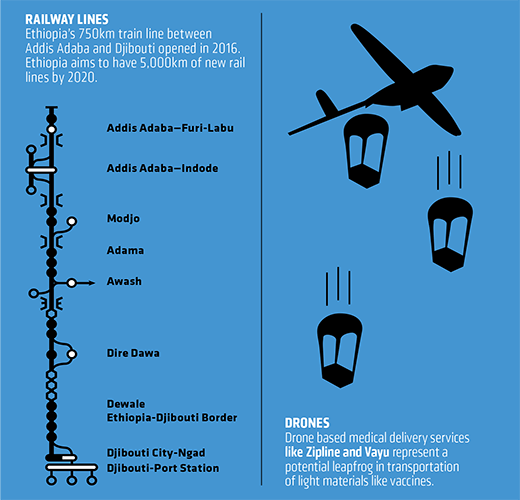

In spite of these innovative solutions, the role of governments in improving transit access cannot be fully supplanted. Governments spending on infrastructure through road, railway and bridge construction plays the most significant role in improved transport connectivity in Africa, as in most places. Ethiopia, for instance, inaugurated a new railway line, linking Addis Ababa with Djibouti in October 2016. The 750-kilometer line was built at a cost of US$4 billion, with backing from China. Ethiopia aims to have 5,000 kilometers of new railway lines by 2020. Nigeria is also investing substantially in transport infrastructure and launched a commuter train service linking the administrative capital, Abuja to major hub, Kaduna.

A final, nascent but evolving transport solution is gaining traction in Africa: drones. The technology has the potential to leapfrog transport inadequacies, particularly in rural areas in the short-term. Drones from Zipline and Vayu, for example, are being used to make medical supply deliveries to and from remote areas in East Africa.

Indeed, short-term and long-term transport solutions are needed across Africa’s rural landscape. A report from the World Bank and SSATP found that “a 100 percent target for rural accessibility would [require] doubling or tripling the length of the existing classified networks in most countries.”

Note: This article was originally published on Medium and can be found here.

No Comments.