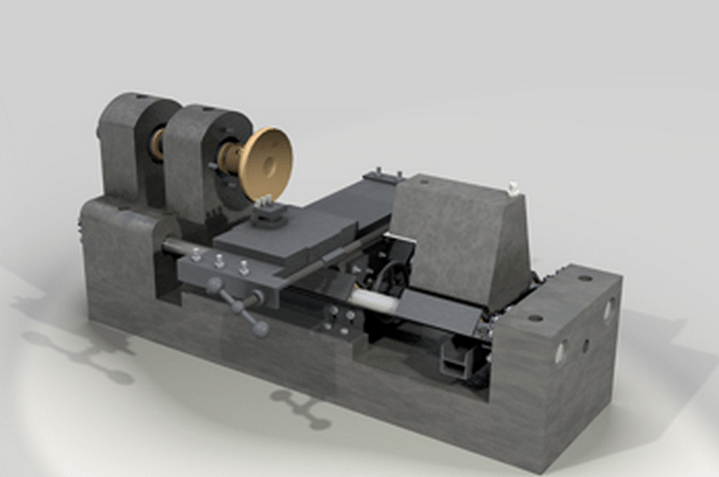

A crew builds a concrete lathe for shaping shells during World War I in this photo that appeared in Machinery magazine in June, 1916.

In the fall of 1917, the United States had declared war on Germany and found its factories better suited for Model T’s than howitzers. The country needed to rev its production engines to make ordnance as quickly as possible. Gun boring and shell shaping, however, required precise, hand- made iron lathes fashioned by journeymen metal workers. Creating the machines needed to create the war machines would take months. Then, an inventor named Lucien Yeomans patented a method for building lathes designed for specific tasks using concrete, pre-fabricated metal and jigs to precisely place the parts. The process eliminated the need for highly skilled handwork, reduced production time by months and costs by so much that the new machines were considered disposable. According to Shannon DeWolfe, Yeoman’s biographer, that lathe was instrumental in the Allies’ success in the war. But the design has fallen into the cracks of history and is no longer in use.

Now, Pat Delany, inventor of the Multimachine, is leading a small group of engineers to revive Yeomans’ technology and put it to more peaceful use in developing countries. This time, though, there are no patents. The design is public, using online collaboration tools and open-source software. Delany’s team is nearing completion of a construction manual for a Yeomans-inspired screw-cutting lathe built with concrete and scrap metal. The goals are two-fold: affordability and precision. And the hope is that these lathes will soon churn out parts for tools and machines, including complex parts such as those that compose engines, pumps, and even other lathes.

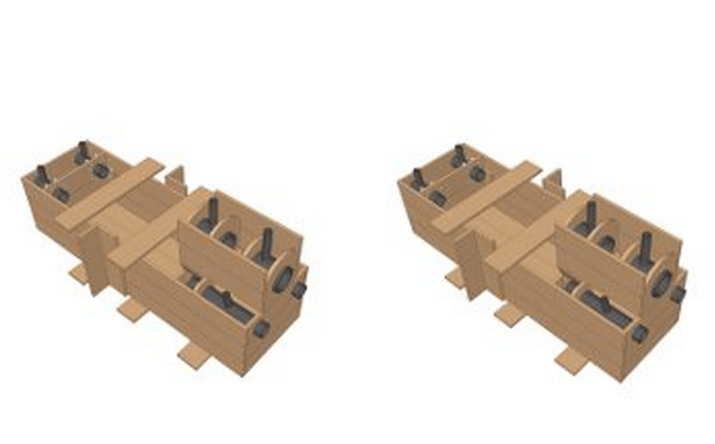

This is one of Tyler Disney’s renderings of the concrete lathe made with free and open-source programs. Image credit: Tyler Disney

Makers needed

Delany is calling on the E4C community for a volunteer to build a 300lb version. The cost of concrete and steel is on him, he says. He plans to show the lathe at Maker Faire Africa in Cairo in October and, afterward, at engineering events in the United States.

“Whoever builds the machine can have it afterward. It would be a great way to learn a vital but forgotten technology,” Delany says. Those interested can contact him through his Open Source Machine Tools group on Yahoo.

Public review

Before unveiling the construction guide, Delany’s team is opening the design to public review. That work should begin soon at the lathe’s online home in a Yahoo group, where Delany has collaborated on his machine designs for the past few years. The lathe has a second home on E4C, too, and supporting documents and new renderings are available here [coming soon].

Disruptive art

The renderings are a new addition to the lather project, the work of Tyler Disney. Disney is an HVAC systems designer with some disruptive ideas about design software.

“I see the use of high-dollar proprietary software tools, like anything from Autodesk, to be at odds with the open-source hardware movement, and not necessary. Open source software lowers the barrier of entry to making quality designs. One of my goals is to push the boundaries of what it means to produce drawings for an open-source hardware project,” Disney tells E4C. “The obvious end use of this ability, as I see it, is in appropriate technology design work.”

In April, Delany called on the E4C community for help making three-dimensional renderings of the concrete lathe. Disney responded with the work shown on this page.

Here is Disney’s collaboration plan, which starts with publicly posting a Sketchup model: “Anyone with a computer and the Internet will be able to download Sketchup for free, open the file, and explore the model to see how the machine is constructed. More importantly, they’ll be able to make tweaks and improvements of their own to the model and share that with the world.” Then, he will import the Sketchup geometry into the open- source modeling and animation program Blender and make realistic renders of the parts, the construction process and how the machine operates.

For more on Disney’s work, see his web site, where he writes descriptively about the lathe and has posted the latest renderings.

For more information: Multimachine and lathe design group on Yahoo